Cyberattaque HubEE : rupture silencieuse de la confiance numérique. Cette attaque, qui a permis l’exfiltration de 160 000 documents sensibles entre le 4 et le 9 janvier 2026, ne relève pas d’un incident isolé. Au contraire, elle révèle une fragilité structurelle au cœur de l’architecture étatique, là où la compromission ne ressemble plus à un piratage classique. Parce que l’intrusion exploite les mécanismes légitimes du système, elle expose un glissement profond : la sécurité ne dépend plus seulement du code, mais du modèle de confiance qui organise les flux administratifs.

Résumé express — Cyberattaque HubEE

Qu’est‑ce que HubEE ?

HubEE est le Hub d’Échange de l’État, la plateforme centrale qui assure la transmission des documents administratifs entre les administrations françaises et les téléservices publics.

Selon la DINUM, HubEE est un tiers de transmission reliant :

- les Services Instructeurs (mairies, conseils départementaux, ministères, opérateurs sociaux) ;

- les Opérateurs de Services en Ligne comme la DILA (Service‑public.fr), la DGS ou la CNAF.

Concrètement, HubEE reçoit les documents envoyés par les usagers via les téléservices, les décrypte puis les redistribue aux administrations concernées. Il fonctionne comme la poste électronique de l’État.

Parce qu’il centralise les flux documentaires, HubEE constitue un point unique de défaillance : une intrusion dans cette plateforme expose potentiellement l’ensemble des administrations connectées.

⚡ La découverte

La Cyberattaque HubEE a été détectée le 9 janvier 2026, après cinq jours d’intrusion discrète. Les attaquants ont exfiltré 160 000 documents sensibles issus d’environ 70 000 dossiers administratifs, sans perturber le fonctionnement du service. L’État a confirmé l’incident le 16 janvier, tout en minimisant la portée structurelle de la compromission.

✦ Impact immédiat

- Exfiltration de documents d’identité, justificatifs de revenus et pièces sociales

- Compromission possible d’identifiants prestataires

- Risque d’usurpation d’identité, fraude sociale et revente ciblée

- Absence de notification individuelle claire pour les usagers concernés

⚠ Message stratégique

L’incident révèle une rupture profonde : l’attaque n’exploite pas une faille logicielle isolée, mais l’architecture même du système. En effet, HubEE repose sur un modèle centralisé où la confiance est héritée, non vérifiée. Dès lors, un attaquant qui obtient un accès légitime peut agir dans le flux, sans alerte, tandis que le chiffrement en transit ne protège pas les documents une fois arrivés dans l’infrastructure.

⎔ Contre‑mesure souveraine

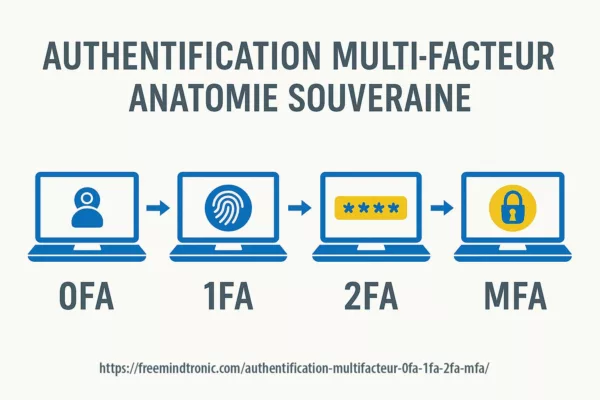

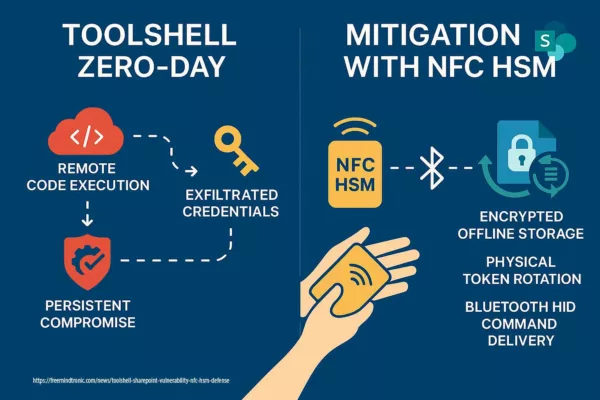

La réduction du risque passe par trois leviers complémentaires :

- DataShielder HSM PGP — chiffrement hors‑ligne maîtrisé par l’usager, empêchant toute lecture par un intermédiaire

- CryptPeer / EviLink — communication distribuée sans serveur, supprimant le point unique de défaillance

- PassCypher HSM PGP Free — authentification passwordless et OTP hors‑ligne, éliminant l’héritage de privilèges

Le Résumé enrichi replace l’incident dans une dynamique plus large : celle d’un modèle étatique où la centralisation, la sous‑traitance et la confiance implicite créent une surface d’attaque systémique.

Paramètres de lecture

Résumé express : ≈ 1 min

Résumé avancé : ≈ 4 min

Chronique complète : ≈ 32 min

Date de publication : 2026-01-17

Dernière mise à jour : 2026-01-18

Niveau de complexité : Souverain & géopolitique

Densité technique : ≈ 72 %

Langues disponibles : FR · EN · ES · CAT

Focal thématique : HubEE, service-public.fr, données personnelles, architecture étatique

Type éditorial : Enquête — Freemindtronic Digital Security Series

Niveau d’enjeu : 8.7 / 10 — souveraineté & données

Références officielles

Les éléments techniques, juridiques et méthodologiques évoqués dans ce dossier s’appuient sur des sources institutionnelles reconnues, garantissant la vérifiabilité et la neutralité des informations présentées.

- DINUM — Communiqués officiels et documentation sur les plateformes d’intermédiation de l’État

- ANSSI — Recommandations de sécurité, guides d’architecture et doctrine de réduction des points de concentration

- CNIL — Obligations légales en cas de violation de données personnelles et notifications aux personnes concernées

- RGPD — Articles 32 et 33 relatifs à la sécurité du traitement et à la notification des violations

- NIST SP 800‑207 — Zero Trust Architecture (référence internationale sur les modèles de confiance distribuée

Elles prolongent l’analyse des architectures centralisées, des risques systémiques liés aux plateformes d’intermédiation étatiques, et des conséquences citoyennes des fuites de données administratives.

Cette sélection complète la présente chronique dédiée à la Cyberattaque HubEE (2026) et aux failles structurelles d’un modèle fondé sur la concentration des flux, la dépendance aux prestataires tiers, et l’absence de chiffrement souverain.

Chapitre 1 — Une confirmation tardive, un récit maîtrisé

La Cyberattaque HubEE a été détectée le 9 janvier 2026, mais l’État n’a communiqué publiquement que le 16 janvier.

Cette temporalité, bien que conforme aux obligations minimales prévues par le cadre de notification des violations de données défini par la CNIL, révèle une stratégie de communication prudente.

En effet, la DINUM a choisi de présenter l’incident comme un événement circonscrit, alors que l’exfiltration de 160 000 documents démontre une compromission bien plus profonde.

Ainsi, la première semaine a servi à contenir le récit autant qu’à contenir l’attaque.

Dès l’annonce officielle, le discours a insisté sur deux éléments : l’absence d’impact sur Service‑public.fr et la maîtrise rapide de l’incident.

Cependant, cette formulation crée une ambiguïté, car elle distingue la plateforme visible du public de l’infrastructure réelle qui traite les documents — une distinction pourtant documentée dans les architectures d’intermédiation de l’État.

Par conséquent, la communication institutionnelle a minimisé la portée systémique de l’intrusion, tout en évitant de préciser la nature exacte des données compromises, contrairement aux recommandations de transparence formulées par la CNIL en cas de fuite de données sensibles.

Cette gestion du calendrier, combinée à un vocabulaire soigneusement choisi, montre que la communication a été calibrée pour rassurer plutôt que pour exposer la réalité structurelle de la compromission.

Dès lors, le récit officiel s’est construit autour d’une idée simple : l’incident est maîtrisé, même si les causes profondes restent floues.

Chapitre 2 — HubEE : un maillon invisible devenu point de rupture

HubEE fonctionne comme un hub d’échange documentaire entre les administrations françaises.

Bien qu’invisible pour les citoyens, il constitue un maillon central du parcours administratif.

Ainsi, lorsqu’un usager transmet un justificatif via Service‑public.fr, HubEE assure la circulation du document vers les organismes concernés, notamment la CNAF.

Cette position stratégique transforme HubEE en point de passage obligé, et donc en cible privilégiée.

Parce que la plateforme centralise les flux, elle concentre également les risques.

Dès lors, une intrusion dans HubEE ne touche pas un service isolé, mais l’ensemble des administrations connectées.

Cette architecture, conçue pour simplifier les échanges, crée paradoxalement un point unique de défaillance.

Ainsi, l’attaque ne compromet pas seulement un système : elle fragilise un écosystème entier.

En outre, la plupart des usagers ignorent l’existence même de HubEE.

Cette invisibilité complique la perception du risque, car elle masque la réalité des flux documentaires.

Par conséquent, l’incident révèle un paradoxe : plus une infrastructure est invisible, plus son impact est massif lorsqu’elle cède.

Chapitre 3 — Une intrusion qui révèle une faille d’architecture

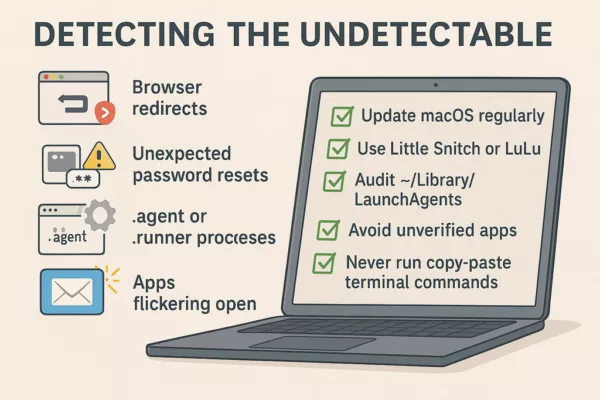

L’intrusion s’est déroulée entre le 4 et le 9 janvier 2026, sans perturber le fonctionnement du service.

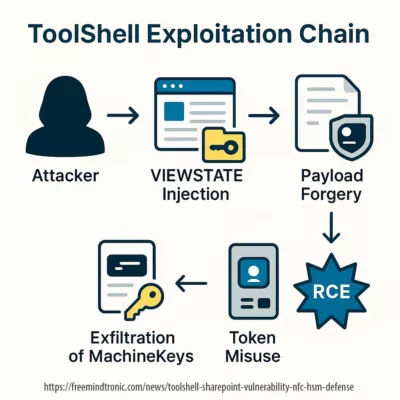

Cette discrétion indique que les attaquants ont utilisé un accès légitime ou un mécanisme interne, plutôt qu’une exploitation bruyante.

Ainsi, la Cyberattaque HubEE ne résulte pas d’un piratage classique, mais d’un détournement de confiance.

Parce que HubEE déchiffre les documents pour les redistribuer, l’attaquant a pu accéder à des données en clair.

Dès lors, le chiffrement en transit ne suffit plus : la faille réside dans l’absence de chiffrement de bout en bout.

Cette architecture, héritée d’un modèle centralisé, expose les documents dès qu’ils atteignent l’infrastructure.

L’incident montre que la sécurité d’un système ne dépend pas uniquement de ses correctifs techniques, mais de la manière dont il organise la confiance.

Ainsi, une architecture qui accorde trop de privilèges à un point central devient vulnérable, même si elle applique toutes les bonnes pratiques apparentes.

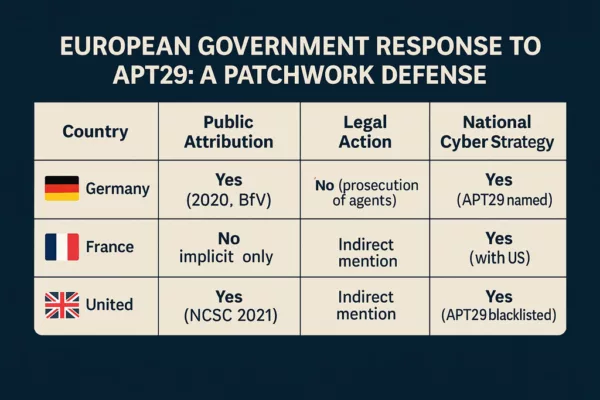

Chapitre 6 — Les contradictions du discours officiel

Dès les premières déclarations, plusieurs contradictions ont émergé dans le discours institutionnel.

Alors que la DINUM affirmait que l’incident était « maîtrisé », elle reconnaissait simultanément que l’exfiltration avait duré cinq jours sans être détectée.

Ainsi, la communication oscillait entre volonté de rassurer et nécessité de reconnaître l’ampleur de la compromission.

De plus, l’État a insisté sur le fait que Service‑public.fr n’était pas touché.

Cependant, cette précision détourne l’attention du véritable problème : ce n’est pas la façade visible qui a été compromise, mais l’infrastructure qui traite les documents.

Par conséquent, la distinction entre la plateforme et son moteur interne a créé une confusion qui a minimisé la perception du risque.

Enfin, les autorités ont évoqué une « intrusion maîtrisée » sans expliquer comment un attaquant a pu agir pendant plusieurs jours dans un système censé être surveillé.

Cette formulation, volontairement vague, laisse entendre que la détection n’a pas fonctionné comme prévu.

Ainsi, les contradictions du discours officiel révèlent une tension entre transparence et préservation de l’image de l’État numérique.

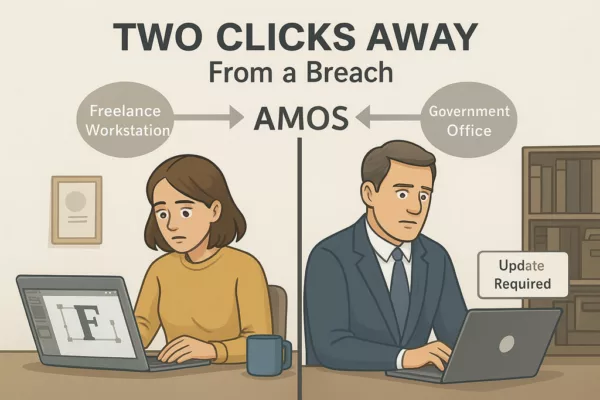

Chapitre 4 — Le sous‑traitant fantôme : l’angle mort de la communication

Dès les premières communications, un élément a attiré l’attention : la mention d’un sous‑traitant impliqué dans la compromission.

Cependant, ni son nom, ni son rôle précis, ni la nature de son accès n’ont été rendus publics.

Cette absence d’information crée un angle mort majeur, car elle empêche d’évaluer la chaîne de confiance réelle derrière HubEE.

En effet, lorsqu’un prestataire détient des accès techniques ou opérationnels, il devient un maillon critique de la sécurité.

Ainsi, si ses identifiants sont compromis, l’attaquant hérite automatiquement de ses privilèges.

Dès lors, la Cyberattaque HubEE révèle un problème structurel : la délégation de confiance à des acteurs invisibles, sans contrôle cryptographique indépendant.

Cette opacité complique également la compréhension du périmètre exact de l’intrusion.

Parce que le prestataire n’est pas identifié, il est impossible de savoir s’il intervenait sur l’infrastructure, sur la maintenance, sur les flux documentaires ou sur la supervision.

Par conséquent, l’incident met en lumière une fragilité récurrente des services publics numériques : la dépendance à des tiers dont la sécurité conditionne celle de l’État.

Résumé enrichi — Quand la Cyberattaque HubEE révèle une rupture de confiance

Du constat factuel à la dynamique structurelle

Ce résumé enrichi complète le premier niveau de lecture. Il ne se limite pas à décrire l’exfiltration des 160 000 documents.

Au contraire, il replace la Cyberattaque HubEE dans une dynamique plus profonde : celle d’un modèle administratif centralisé où la confiance repose sur l’infrastructure, tandis que la vérification cryptographique reste absente.

Ainsi, l’incident ne constitue pas une anomalie, mais le symptôme d’un système qui accorde trop de privilèges à ses propres mécanismes internes.

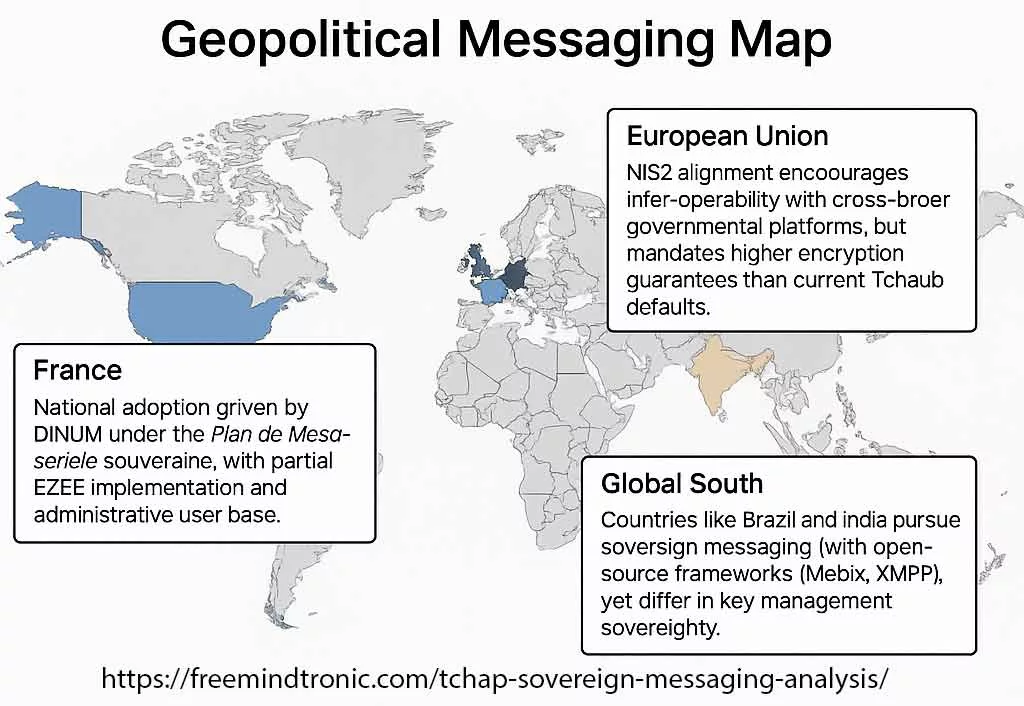

Le modèle historique de l’État numérique : centralisation et héritage

Historiquement, les plateformes administratives ont été conçues autour d’un principe simple : un hub central, plusieurs administrations connectées, un flux unifié.

Ce modèle, efficace en apparence, crée cependant une corrélation dangereuse : un accès légitime équivaut à une légitimité totale.

Dès lors, la sécurité dépend moins du chiffrement que de la capacité à protéger un point unique de confiance.

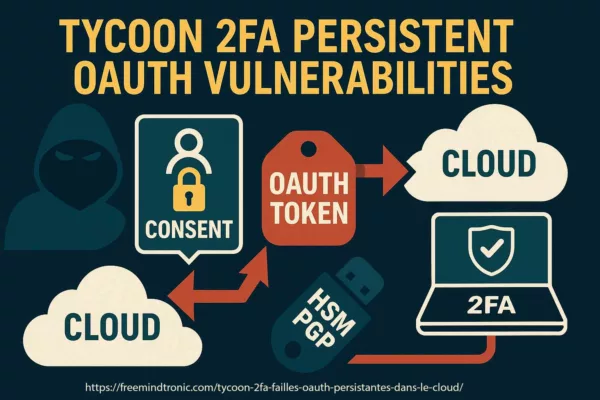

L’héritage de confiance comme vecteur d’attaque

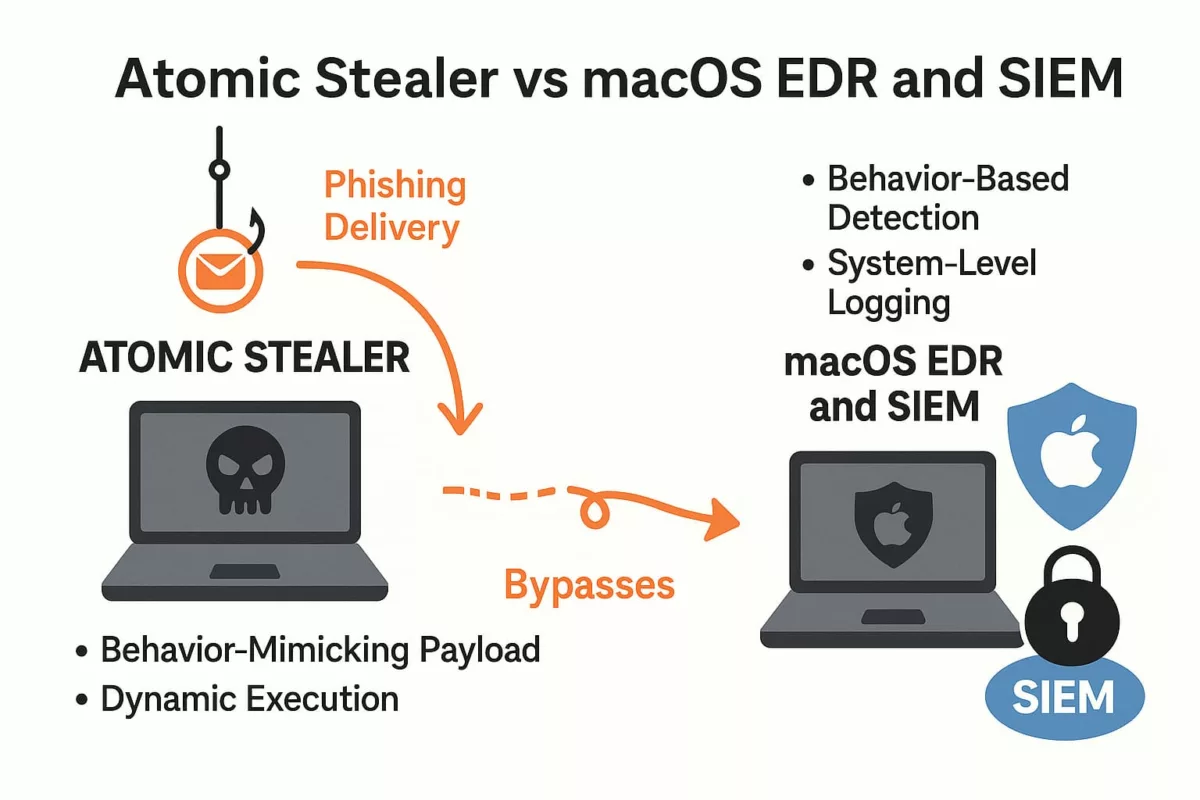

Dans ce contexte, un attaquant n’a plus besoin de casser un système.

Il lui suffit d’hériter d’un accès déjà autorisé — par exemple via un compte prestataire compromis ou un jeton valide.

Parce que HubEE considère cet accès comme légitime, l’attaquant peut alors agir dans le flux, sans provoquer d’alerte.

Le chiffrement en transit fonctionne, mais il protège uniquement le transport, pas l’environnement déjà compromis.

De la vulnérabilité technique à la bascule stratégique

C’est ici que se situe la véritable rupture.

Contrairement aux attaques classiques, l’intrusion HubEE ne repose pas sur une faille logicielle isolée.

Elle exploite la logique même du système : centralisation, héritage de privilèges, absence de cloisonnement et confiance implicite.

Par conséquent, la détection devient secondaire, puisque l’attaque n’enfreint aucune règle apparente.

Quand le risque quitte le code pour l’architecture de confiance

Cette invisibilité opérationnelle remet en cause l’idée selon laquelle la sécurité d’un service public peut être évaluée uniquement à travers ses correctifs techniques.

Lorsque l’attaque exploite la structure même de la confiance, la surface de risque se déplace : elle ne réside plus dans le code, mais dans la manière dont l’État organise, délègue et centralise ses flux documentaires.

Ce qu’il faut retenir

- Le chiffrement protège les flux, pas les documents une fois arrivés dans HubEE.

- Un accès légitime n’est pas synonyme d’utilisateur légitime.

- La centralisation amplifie mécaniquement l’impact d’une intrusion.

- L’attaque devient invisible lorsqu’elle exploite les mécanismes normaux du système.

Chapitre 7 — Les risques concrets pour les citoyens

L’exfiltration de 160 000 documents expose les citoyens à des risques immédiats et différés.

Selon les analyses publiées par la CNIL, les fuites de pièces d’identité, de justificatifs de revenus ou de documents sociaux constituent l’un des vecteurs les plus critiques d’usurpation et de fraude.

Parce que les pièces compromises incluent des justificatifs d’identité, de revenus et de situation familiale, elles peuvent alimenter des fraudes ciblées.

Ainsi, les victimes potentielles ne sont pas seulement les usagers concernés, mais aussi les organismes sociaux qui devront gérer les conséquences, comme l’ont déjà souligné plusieurs autorités publiques dans des cas similaires.

Le premier risque est l’usurpation d’identité.

Avec un justificatif de domicile, une pièce d’identité et un document social, un attaquant peut constituer un dossier complet pour ouvrir des comptes, contracter des crédits ou détourner des prestations — un scénario explicitement décrit dans les recommandations de la CNIL sur les violations de données sensibles.

Le second risque concerne la fraude sociale.

Les documents exfiltrés peuvent permettre de simuler des situations familiales ou financières, ce qui fragilise les dispositifs d’aide.

La ANSSI rappelle que les données administratives constituent un matériau privilégié pour les attaques d’ingénierie sociale, notamment lorsqu’elles sont revendues sur des marchés spécialisés et utilisées pour des campagnes de phishing ciblé.

Enfin, l’absence de notification individuelle claire complique la capacité des citoyens à se protéger.

Selon la CNIL, la transparence envers les personnes concernées est un élément essentiel de la limitation des risques, car elle leur permet de surveiller leurs comptes, d’anticiper les tentatives d’usurpation et de prendre des mesures préventives.

Ainsi, l’impact réel de la Cyberattaque HubEE pourrait se révéler progressivement, au fil des mois, comme cela a été observé dans d’autres incidents impliquant des données administratives sensibles.

Chapitre 8 — Les responsabilités politiques et techniques

La Cyberattaque HubEE met en lumière une responsabilité partagée entre les acteurs politiques, les équipes techniques et les prestataires.

Parce que HubEE constitue un maillon central de l’État numérique, sa sécurité relève autant de la gouvernance que de la technique.

Ainsi, l’incident révèle une chaîne de responsabilités qui dépasse largement la seule DINUM.

Sur le plan politique, la centralisation des services administratifs a été encouragée pour simplifier les démarches.

Cependant, cette stratégie n’a pas été accompagnée d’une réflexion équivalente sur la segmentation cryptographique ou la souveraineté des flux.

Dès lors, l’État a construit une architecture efficace, mais vulnérable par conception.

Sur le plan technique, la dépendance à des prestataires extérieurs crée une dilution de la responsabilité.

Lorsque plusieurs acteurs interviennent sur une même infrastructure, la sécurité dépend du maillon le plus faible.

Ainsi, l’absence d’identification publique du sous‑traitant empêche d’évaluer la robustesse de la chaîne.

Enfin, la gouvernance de la cybersécurité repose encore trop souvent sur des audits ponctuels, alors que les menaces évoluent en continu.

Par conséquent, l’incident HubEE montre que la sécurité doit devenir un processus permanent, et non une conformité administrative.

Chapitre 9 — Les questions que l’enquête met sur la table

L’enquête ouverte après la Cyberattaque HubEE soulève plusieurs questions essentielles.

Certaines concernent la technique, d’autres la gouvernance, et d’autres encore la transparence.

Ainsi, l’incident agit comme un révélateur des zones d’ombre du modèle administratif actuel.

La première question porte sur l’accès initial : comment un attaquant a‑t‑il pu obtenir un accès légitime ou un jeton valide ?

Cette interrogation conditionne toute la compréhension de l’intrusion.

Si l’accès provient d’un prestataire, alors la chaîne de sous‑traitance doit être réévaluée.

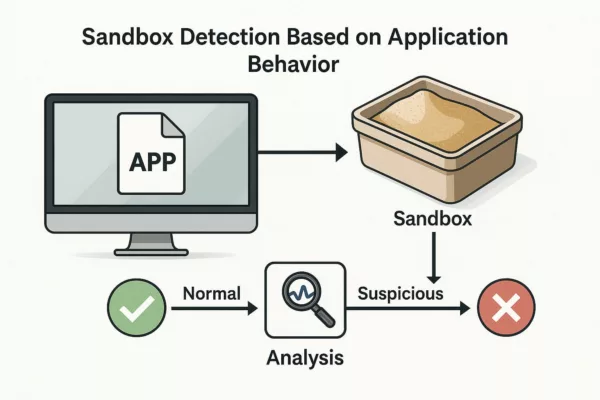

La deuxième question concerne la détection.

Pourquoi l’exfiltration massive de documents n’a‑t‑elle pas déclenché d’alerte ?

Cette absence de signal montre que les mécanismes de surveillance ne sont pas adaptés aux attaques qui exploitent les privilèges internes.

La troisième question touche à la transparence.

Pourquoi les usagers n’ont‑ils pas été informés individuellement ?

Cette omission complique la capacité des citoyens à se protéger, alors que le RGPD impose une notification lorsque le risque est élevé.

Enfin, une question plus large se pose : l’architecture actuelle peut‑elle encore garantir la confiance ?

L’incident montre que la réponse dépend moins du code que du modèle de confiance qui structure les échanges.

Chapitre 5 — Une architecture qui amplifie l’impact

L’architecture de HubEE repose sur un principe simple : centraliser les échanges documentaires pour fluidifier les démarches administratives.

Cependant, cette centralisation crée un effet mécanique : l’impact d’une intrusion augmente proportionnellement au nombre d’administrations connectées.

Ainsi, une faille dans HubEE ne touche pas un service isolé, mais l’ensemble des organismes qui s’appuient sur cette plateforme.

Parce que HubEE reçoit, déchiffre et redistribue les documents, il devient un point de passage incontournable.

Dès lors, l’attaquant qui accède à cette zone peut observer ou exfiltrer des données provenant de multiples sources.

Cette configuration transforme une faille locale en incident national, ce qui explique l’ampleur des 160 000 documents compromis.

En outre, l’absence de cloisonnement strict entre les flux accentue le risque.

Lorsque les documents transitent dans un même espace logique, une compromission permet d’accéder à des données hétérogènes : pièces d’identité, justificatifs de revenus, attestations sociales, documents familiaux.

Ainsi, l’architecture amplifie non seulement le volume, mais aussi la diversité des données exposées.

Cette situation montre que la sécurité ne peut plus reposer sur la seule protection d’un point central.

Au contraire, elle doit s’appuyer sur une segmentation cryptographique, où chaque document reste protégé indépendamment de l’infrastructure qui le transporte.

Chapitre 10 — Comment l’attaque a pu réussir, et par qui

Même si l’enquête judiciaire n’a pas encore identifié les auteurs, plusieurs éléments permettent de comprendre comment l’attaque a pu réussir.

Parce que l’intrusion s’est déroulée sans bruit, elle repose probablement sur un accès légitime ou sur un mécanisme interne détourné.

Ainsi, l’attaquant n’a pas eu besoin de casser le système : il lui a suffi d’en hériter.

Trois hypothèses se dégagent.

La première concerne un compte prestataire compromis.

Si un sous‑traitant disposait d’un accès technique, un simple vol d’identifiants pouvait suffire.

La deuxième hypothèse repose sur un jeton d’accès valide, obtenu via phishing ou compromission locale.

La troisième évoque une intrusion interne, plus rare mais cohérente avec la discrétion de l’attaque.

Dans tous les cas, l’architecture centralisée de HubEE a facilité la progression de l’attaquant.

Parce que les documents sont déchiffrés dans l’infrastructure, l’accès à cette zone permet d’observer ou d’exfiltrer des données en clair.

Ainsi, l’attaque ne révèle pas seulement une faille opérationnelle, mais une faiblesse structurelle.

Enfin, la durée de l’intrusion montre que les mécanismes de détection n’ont pas fonctionné comme prévu.

Cette situation suggère que l’attaquant connaissait bien l’environnement, ce qui renforce l’hypothèse d’un accès hérité plutôt que d’un piratage externe.

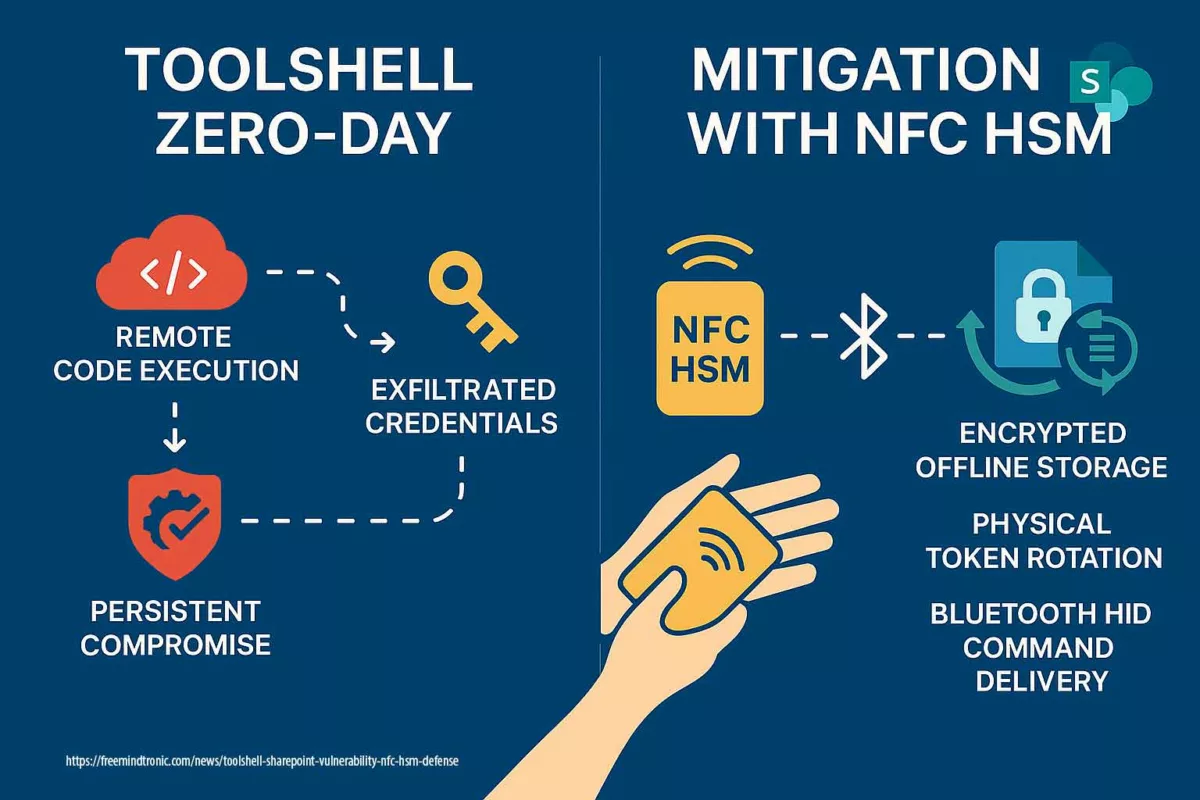

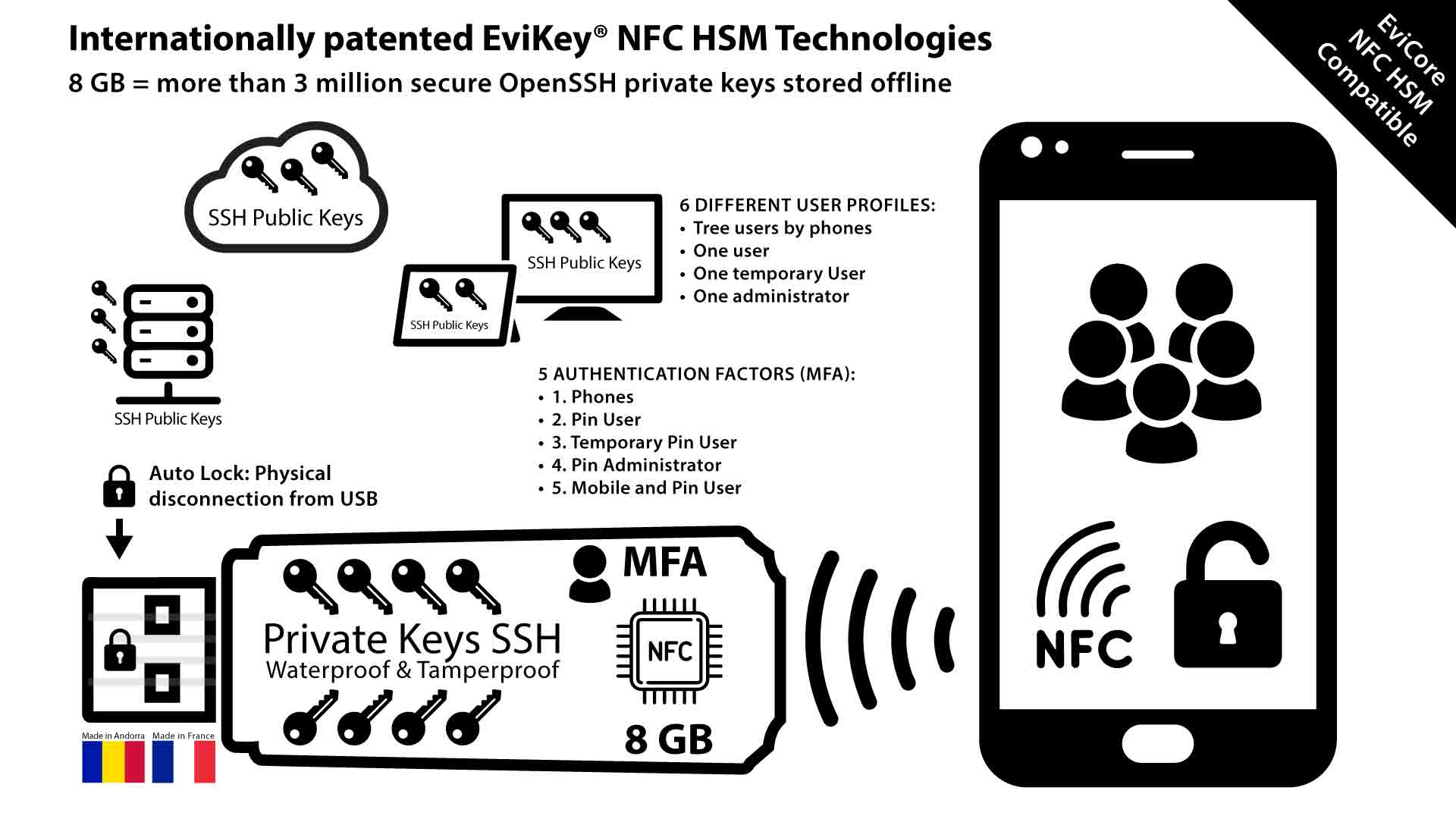

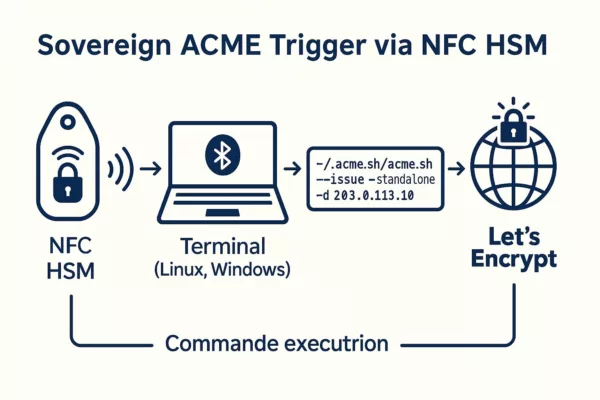

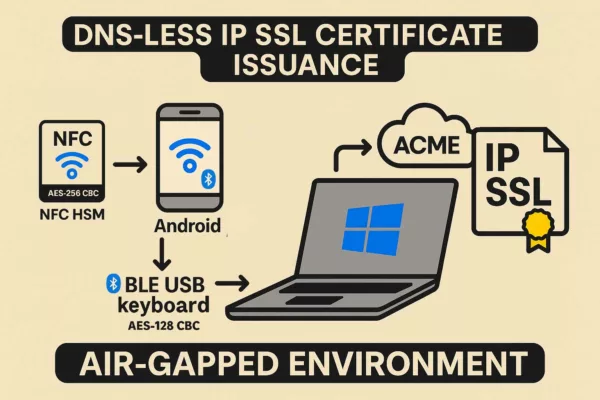

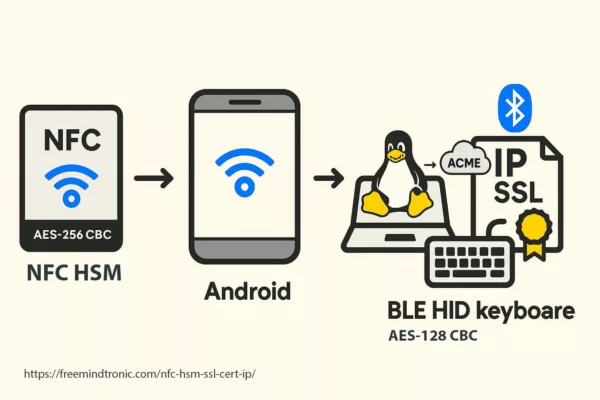

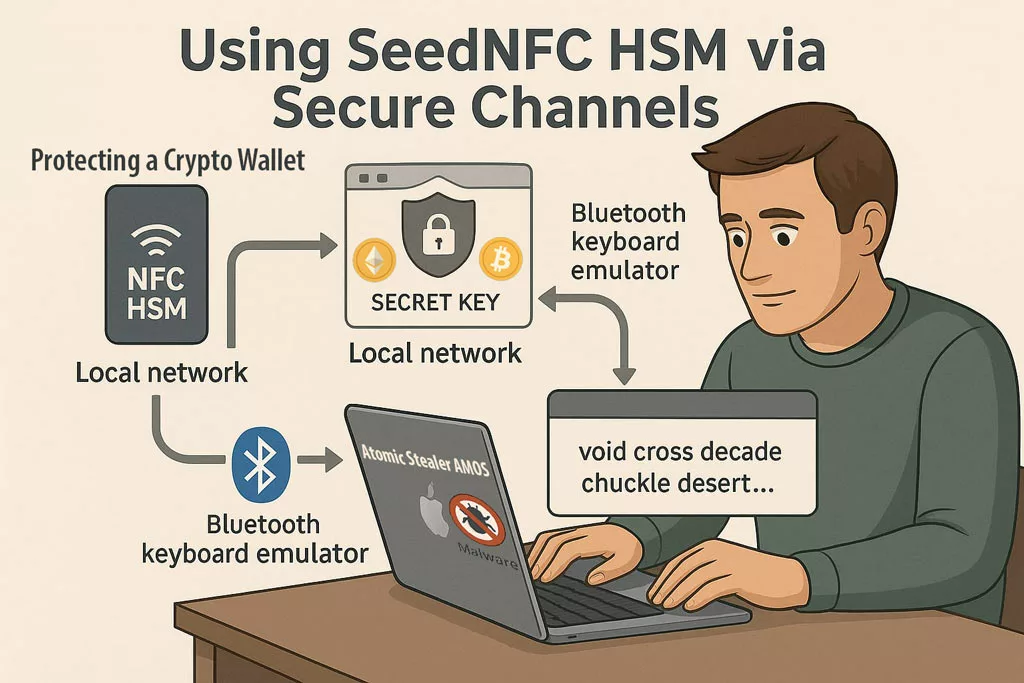

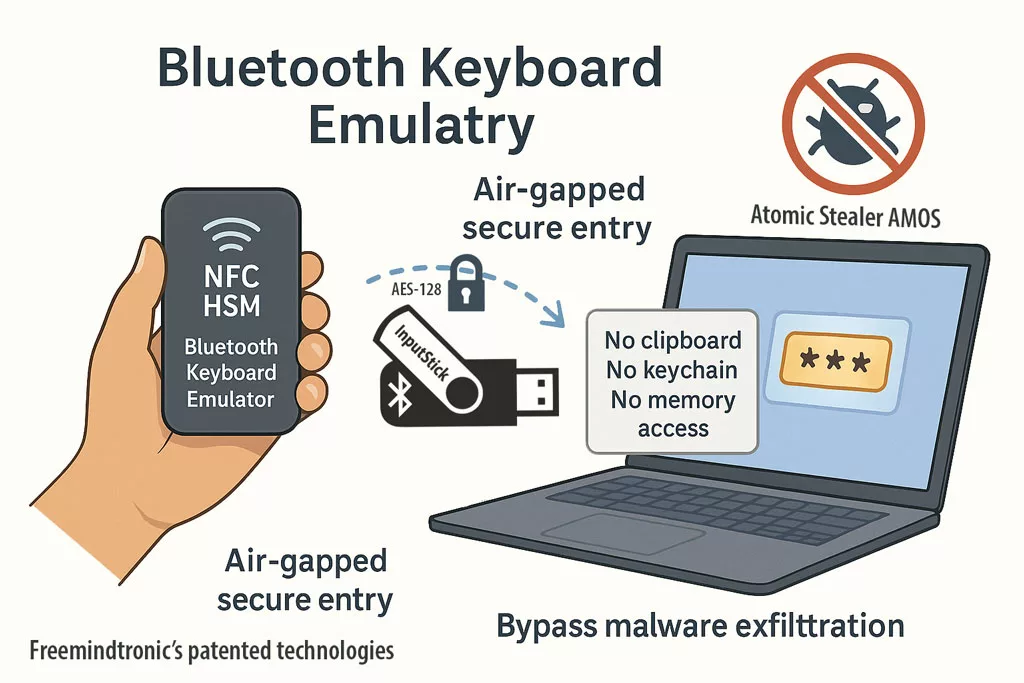

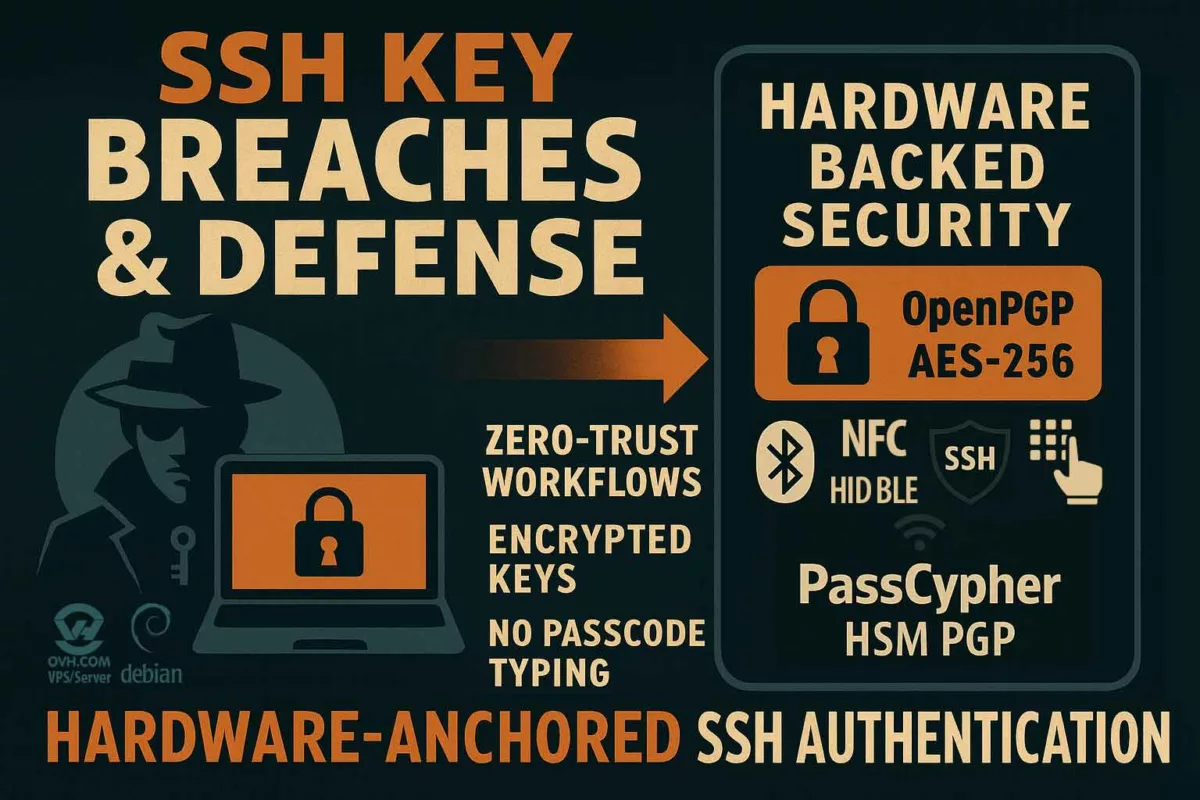

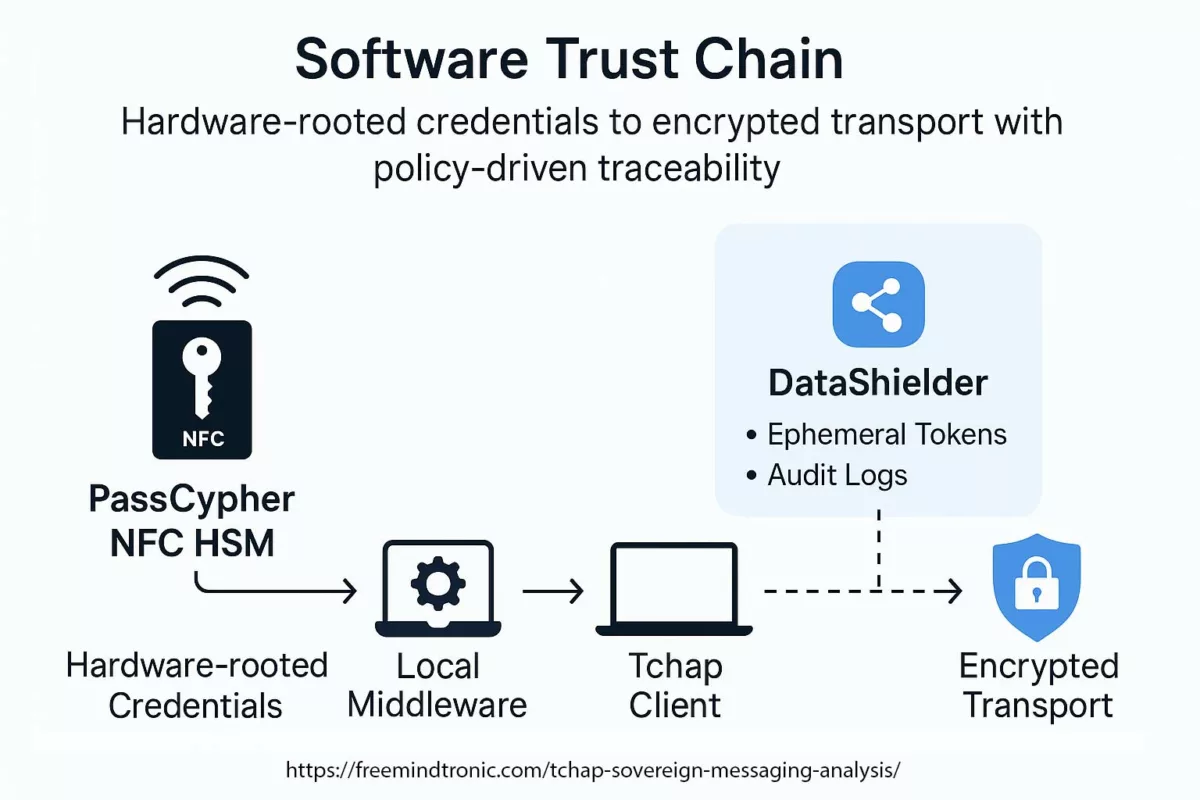

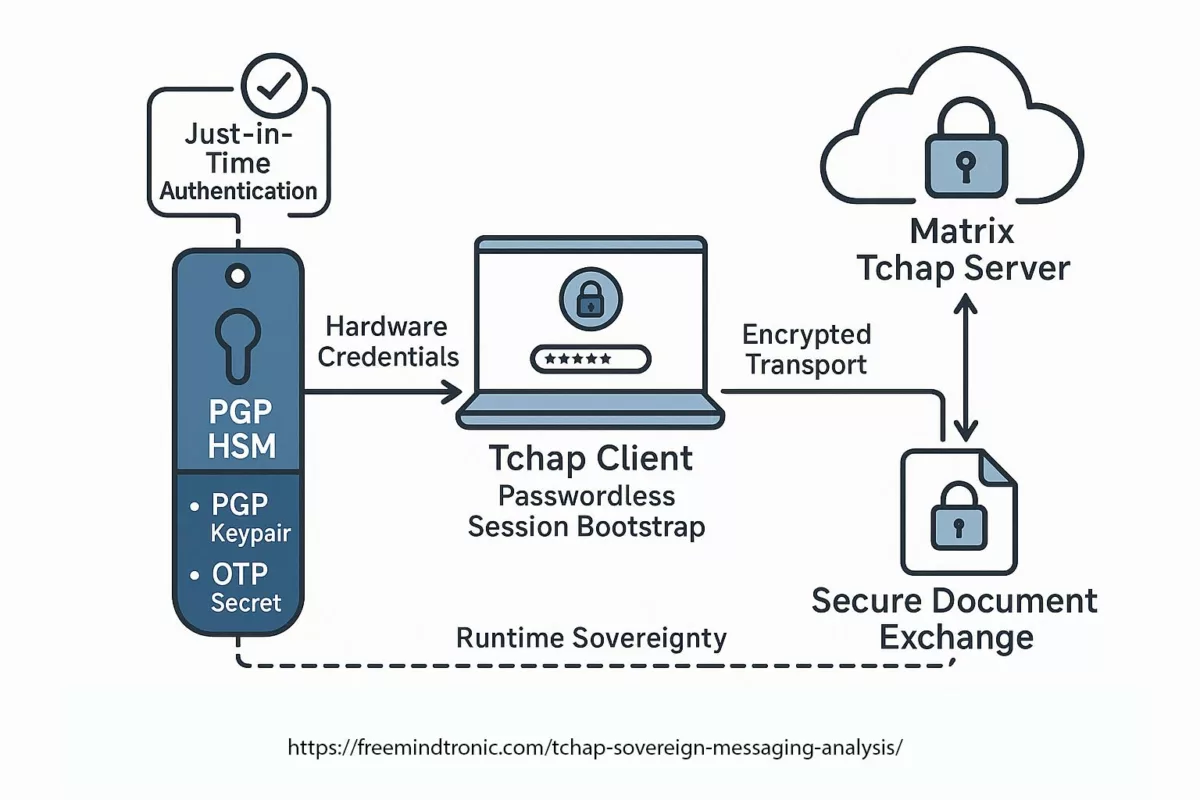

Et si la cible avait utilisé PassCypher NFC HSM / HSM PGP ?

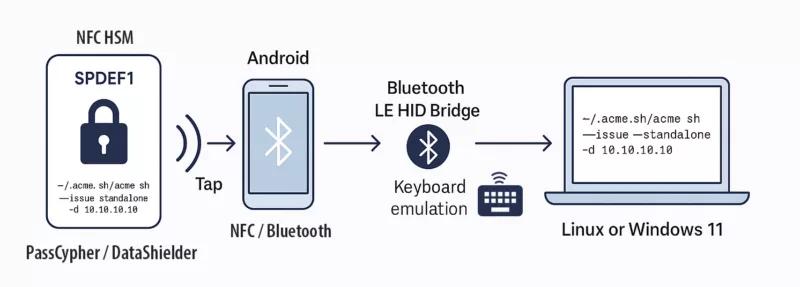

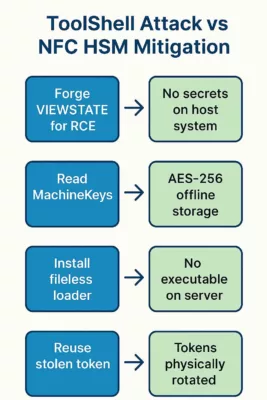

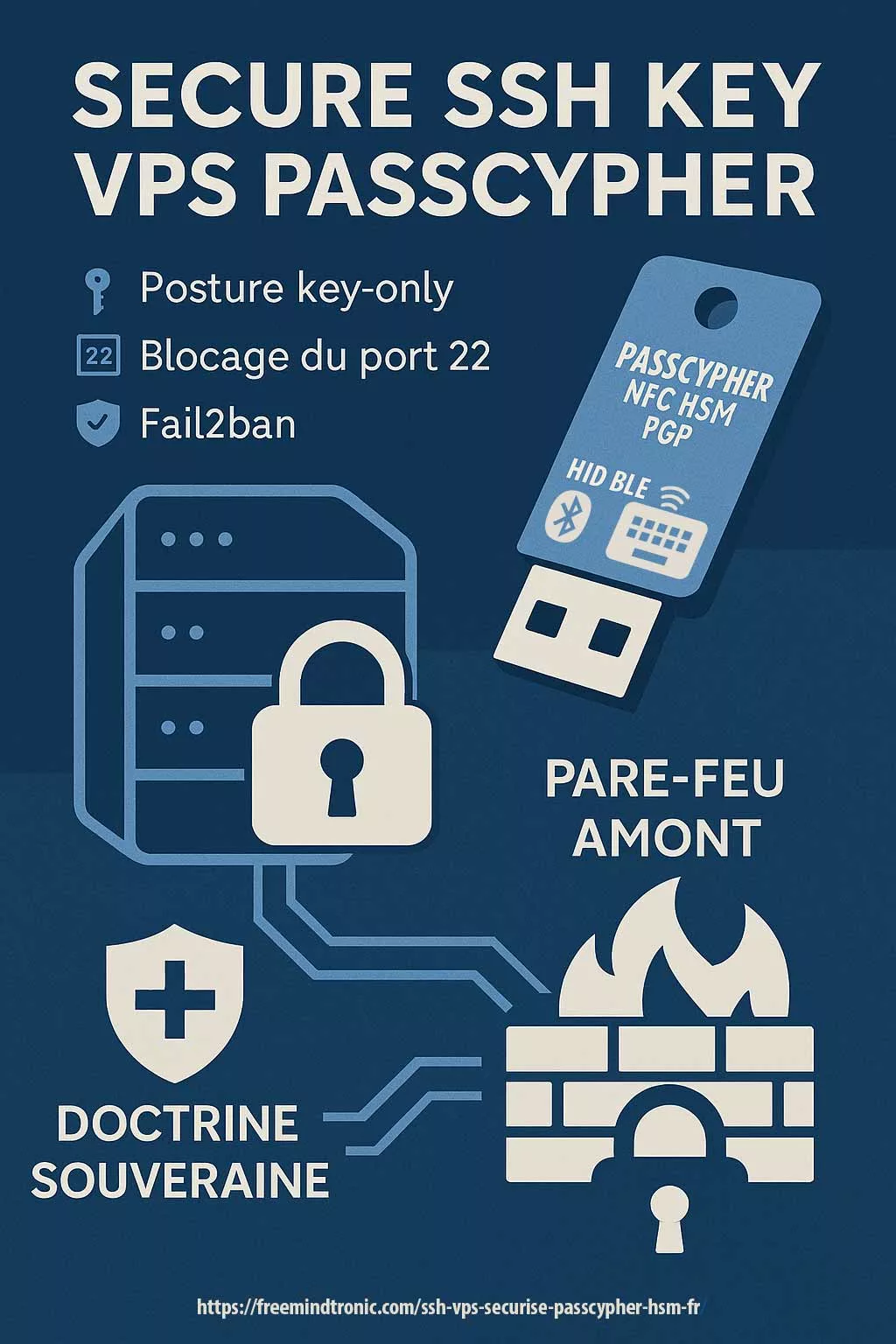

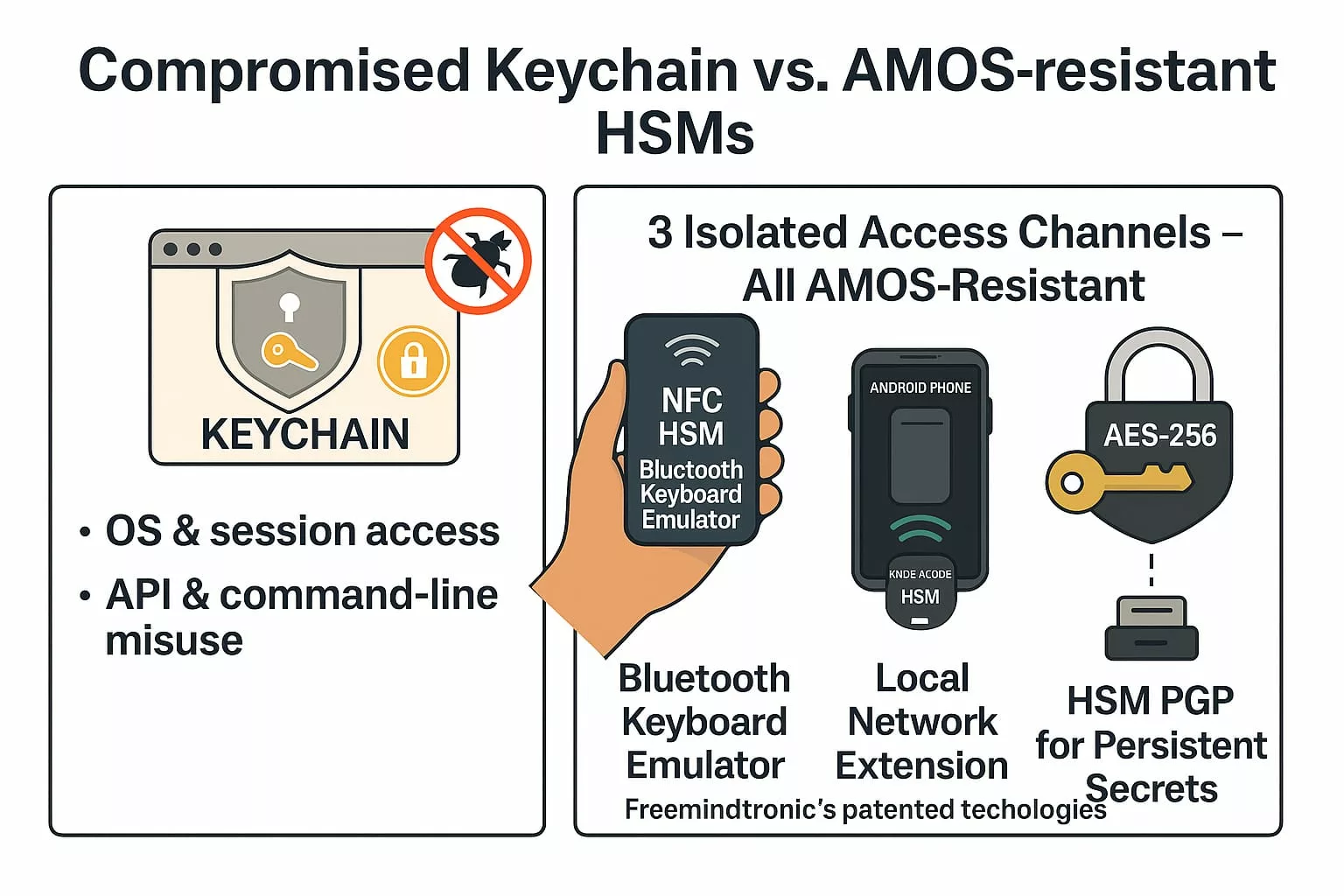

Si les accès prestataires ou administratifs avaient été protégés par PassCypher NFC HSM ou HSM PGP, l’attaque HubEE aurait été structurellement impossible, même avec un accès légitime compromis.

- Aucun identifiant exploitable : PassCypher ne stocke ni mots de passe, ni secrets persistants, ni tokens réutilisables.

- OTP hors-ligne : chaque accès repose sur un code à usage unique généré dans un HSM NFC, impossible à intercepter.

- Aucun accès persistant : l’attaquant ne peut pas maintenir une session ou réutiliser un secret.

- Modèle de confiance inversé : l’identité n’est plus validée par le serveur, mais par le HSM de l’utilisateur.

Dans ce scénario, l’attaque HubEE n’aurait pas pu obtenir d’accès durable, ni contourner les contrôles, ni exploiter un identifiant interne.

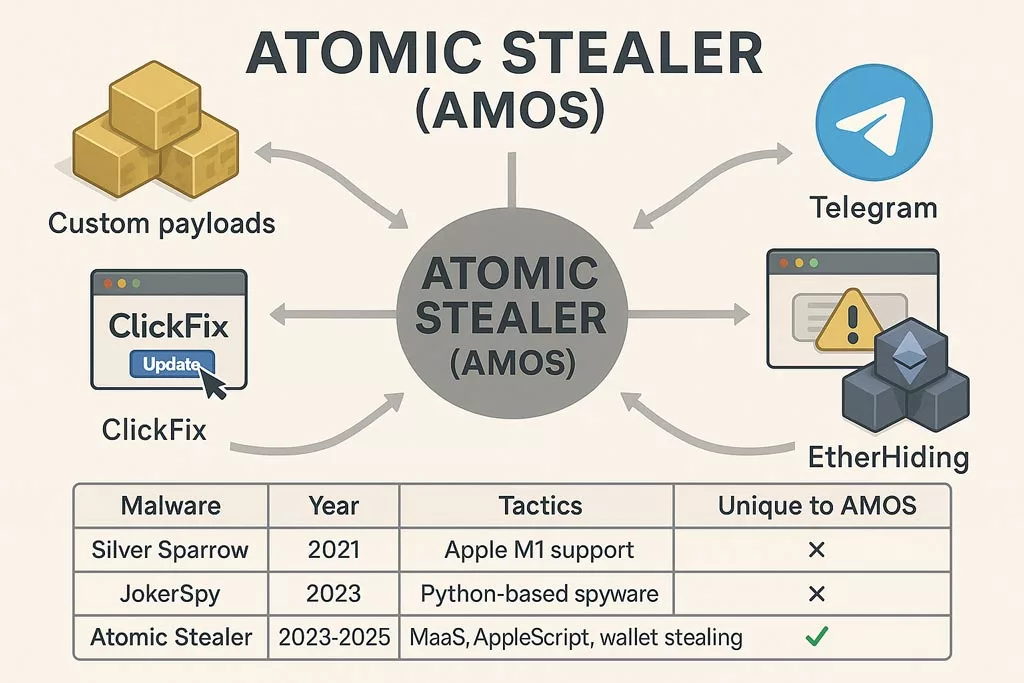

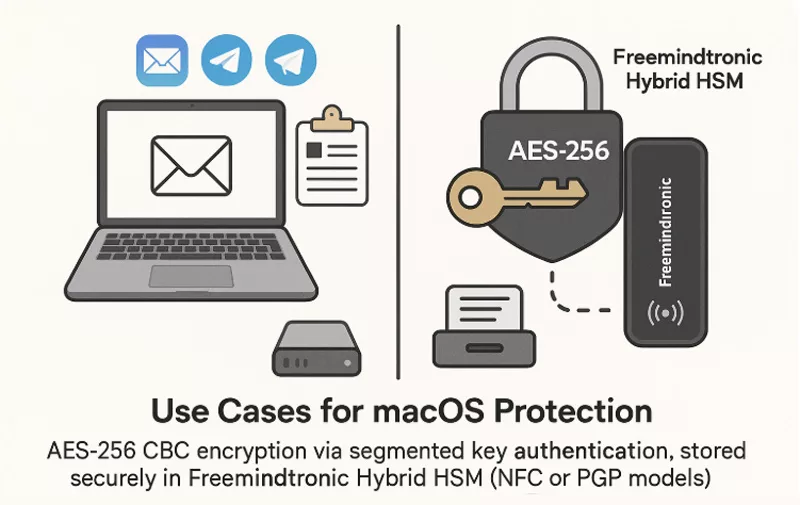

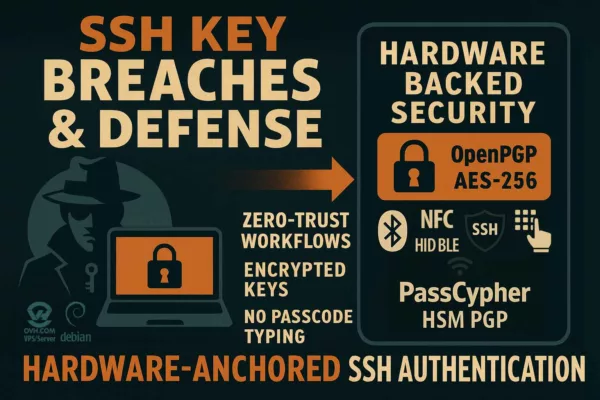

Chapitre 11 — Les alternatives : sortir du modèle vulnérable

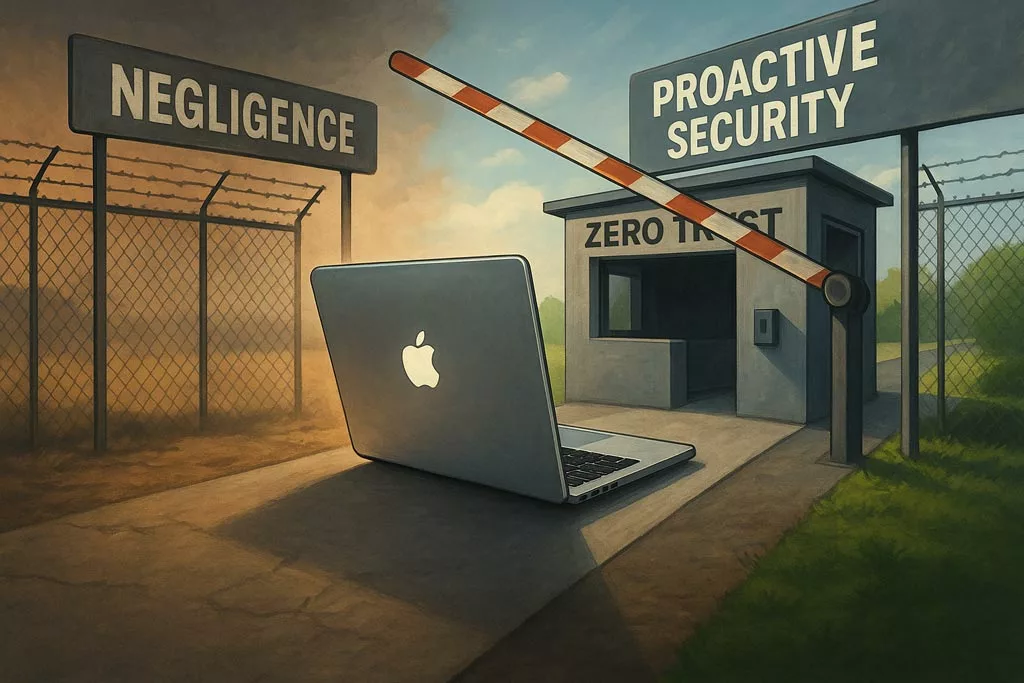

La Cyberattaque HubEE montre que le modèle actuel, fondé sur la centralisation et l’héritage de privilèges, atteint ses limites.

Pour restaurer la confiance, il ne suffit plus de renforcer les contrôles : il faut repenser l’architecture.

Ainsi, la souveraineté numérique passe par une transformation profonde des mécanismes de confiance.

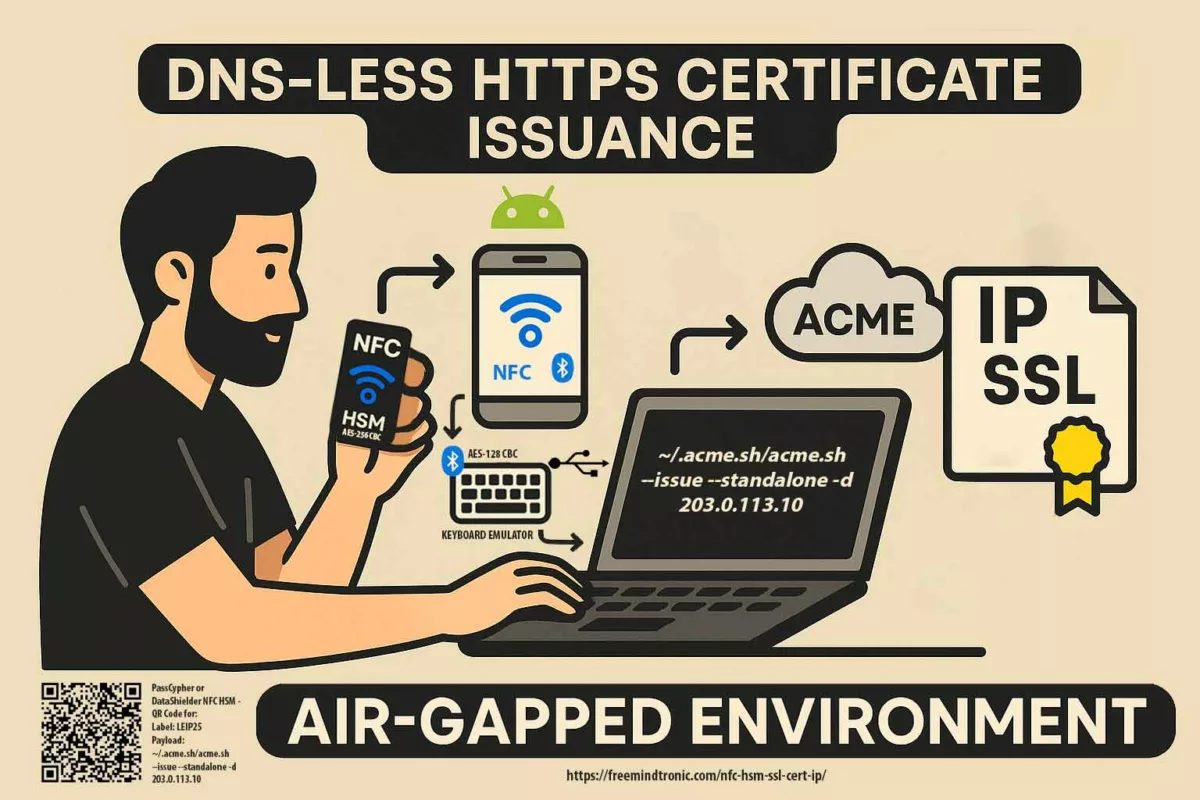

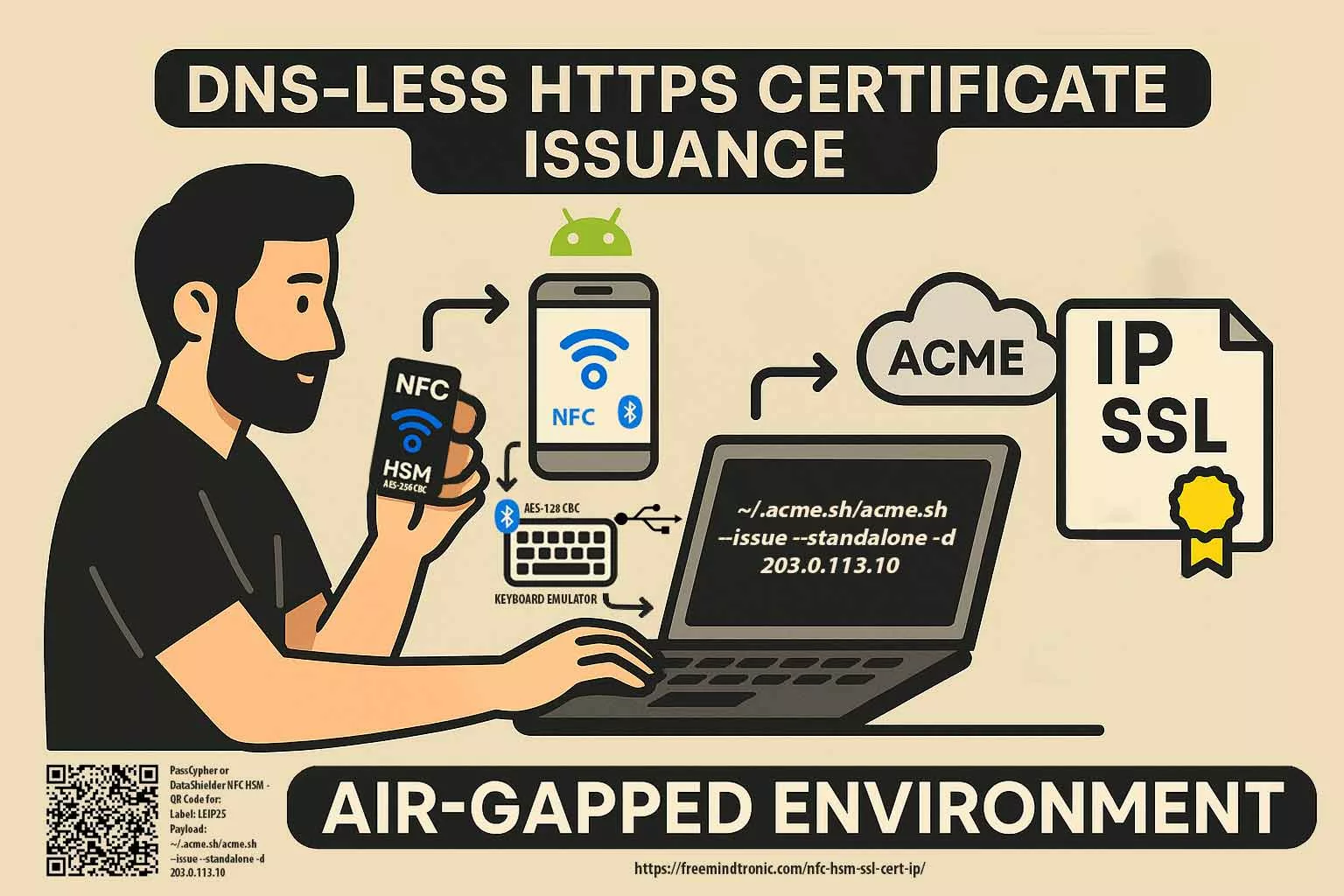

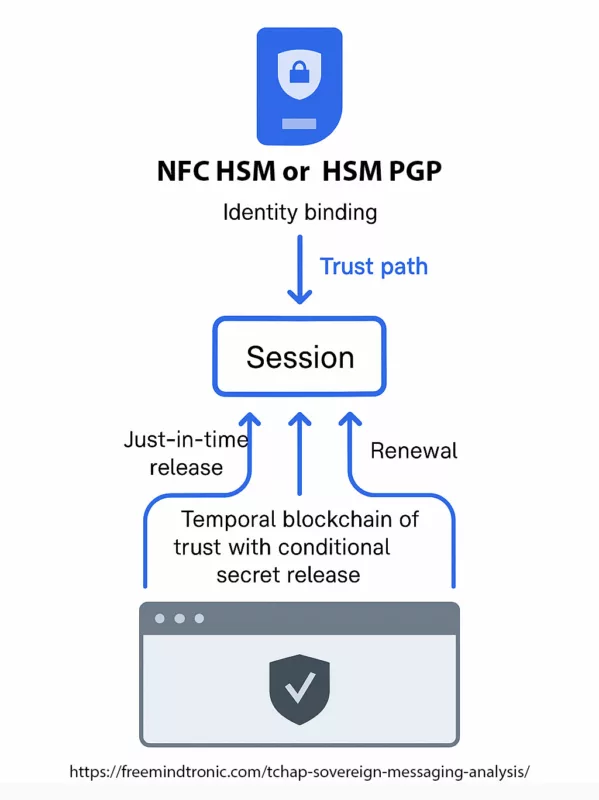

La première alternative consiste à adopter une segmentation cryptographique.

Avec des solutions comme DataShielder HSM PGP, chaque document reste chiffré de bout en bout, indépendamment de l’infrastructure.

Dès lors, même une intrusion dans un hub ne permet plus de lire les données.

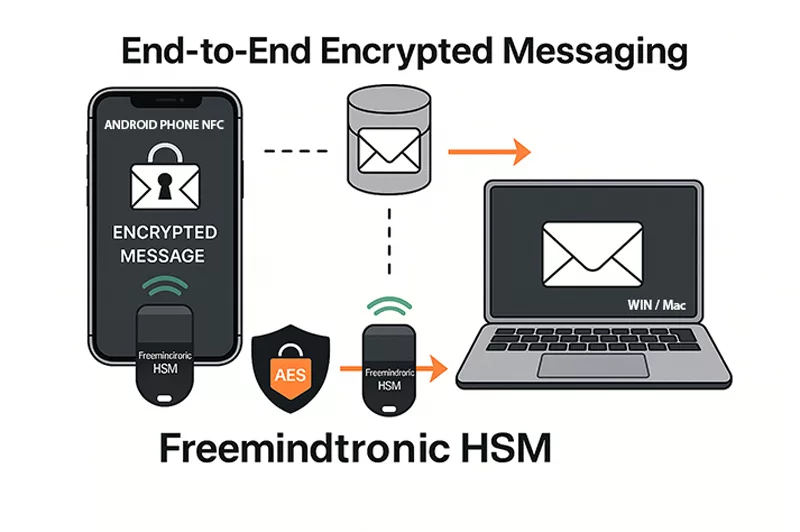

La deuxième alternative repose sur des communications distribuées.

Avec CryptPeer / EviLink, les échanges ne transitent plus par un point central, ce qui élimine le risque de compromission massive. Ainsi, la surface d’attaque se réduit mécaniquement.

La troisième alternative concerne l’authentification.

Avec PassCypher HSM PGP Free, les accès ne reposent plus sur des identifiants persistants, mais sur des OTP hors‑ligne impossibles à intercepter.

Par conséquent, l’héritage de privilèges disparaît.

Ces approches montrent qu’il est possible de construire un modèle où la confiance ne dépend plus d’un hub central, mais d’une cryptographie maîtrisée par l’usager.

Ainsi, la souveraineté numérique devient une réalité opérationnelle, et non un slogan.

Et si les documents avaient été chiffrés avec DataShielder NFC HSM / HSM PGP ?

Si les documents transmis via HubEE avaient été chiffrés en amont avec DataShielder NFC HSM ou HSM PGP, l’exfiltration de 160 000 fichiers n’aurait eu aucune valeur exploitable.

- Chiffrement E2E hors-ligne : les documents sont chiffrés avant l’envoi, dans un HSM NFC.

- Aucune clé côté serveur : HubEE ne peut ni lire ni déchiffrer les documents.

- Exfiltration = blobs chiffrés : même en cas de fuite massive, les données restent cryptographiquement inutilisables.

- Résilience aux attaques internes : même un agent interne ne peut rien exploiter sans le HSM du détenteur.

Dans ce scénario, l’attaque HubEE aurait été un incident technique, pas une catastrophe nationale.

Synthèse : ce que révèlent ces scénarios souverains

Les scénarios PassCypher, DataShielder et CryptPeer démontrent que l’ampleur de la cyberattaque HubEE n’est pas liée à la sophistication de l’attaque, mais au modèle de confiance centralisé sur lequel repose l’architecture actuelle.

Avec une approche souveraine, qu’elle soit déployée indépendamment ou en écosystème, l’impact aurait été radicalement différent :

- les accès n’auraient pas été exploitables grâce à l’authentification hors‑ligne et non réutilisable (PassCypher) ;

- les documents exfiltrés seraient restés illisibles, chiffrés en amont dans le terminal (DataShielder) ;

- les flux n’auraient jamais été interceptables, car ils n’auraient pas transité en clair par un hub central (CryptPeer) ;

- HubEE n’aurait plus constitué un point unique de défaillance ;

- l’architecture étatique aurait été résiliente par conception, et non par réaction.

Qu’elle soit appliquée seule ou combinée, chacune de ces solutions aurait réduit l’incident à un événement mineur — voire l’aurait rendu totalement inopérant. L’attaque HubEE n’aurait pas pu produire les effets systémiques observés.

Contre‑mesures souveraines

La Cyberattaque HubEE montre que la sécurité ne peut plus dépendre d’une infrastructure centralisée où les accès, les documents et les flux convergent vers un même point de défaillance. Les contre‑mesures souveraines doivent agir à la source : sur la cryptographie, l’authentification et la distribution des échanges. Elles réduisent mécaniquement l’impact d’une intrusion, même lorsque l’attaquant obtient un accès légitime.

1. DataShielder HSM PGP — Chiffrement hors‑ligne maîtrisé par l’usager

Avec DataShielder HSM PGP, chaque document est chiffré de bout en bout avant son envoi, directement dans le terminal de l’usager. Même si un attaquant accède à un hub ou à un prestataire, il ne peut rien lire. Cette approche supprime la dépendance à la confiance implicite dans les serveurs.

2. CryptPeer / EviLink — Communications distribuées via un relais aveugle

CryptPeer élimine le point unique de défaillance. Les échanges ne transitent plus en clair par une plateforme centrale, mais par un canal pair‑à‑pair éphémère où le serveur relais ne voit que des blocs AES‑256 déjà chiffrés. Une intrusion dans une infrastructure ne permet plus d’observer ni d’intercepter les flux.

3. PassCypher HSM PGP Free — Authentification sans identifiants persistants

PassCypher remplace les identifiants classiques par des OTP hors‑ligne impossibles à intercepter ou à réutiliser. Un attaquant ne peut plus hériter d’un accès prestataire ou d’un jeton valide. Cette approche supprime l’héritage de privilèges, cœur du problème HubEE.

En combinant ces trois leviers — ou même en les déployant séparément — il devient possible de construire un modèle où la confiance ne repose plus sur l’infrastructure, mais sur la cryptographie maîtrisée par l’usager. Une attaque comparable à HubEE serait alors réduite à un incident mineur, voire rendue impossible.

Il convient également de rappeler que ces technologies souveraines ne sont pas théoriques.

Les versions régaliennes de DataShielder et PassCypher ont été officiellement présentées lors des éditions Eurosatory 2022 et Eurosatory 2024, démontrant leur maturité opérationnelle dans des environnements de défense et de sécurité.

De la même manière, la version régalienne de CryptPeer — incluant l’auto‑hébergement, l’auto‑portabilité et un service complet de client messagerie — sera présentée par AMG PRO partenaire de Freemindtronic à Eurosatory 2026.

Ces présentations successives confirment que ces solutions s’inscrivent dans un écosystème souverain déjà reconnu par les acteurs institutionnels et industriels.

Modèle centralisé vs modèle souverain

| Critère | Modèle centralisé (HubEE) | Modèle souverain (Freemindtronic) |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Point unique de défaillance | Distribution des flux |

| Chiffrement | En transit uniquement | E2E hors‑ligne (HSM PGP) |

| Accès | Identifiants persistants | OTP hors‑ligne |

| Résilience | Impact massif en cas d’intrusion | Impact localisé, cloisonné |

| Confiance | Héritée | Vérifiable cryptographiquement |

HubEE vs Architecture distribuée

| Aspect | HubEE | Architecture distribuée |

|---|---|---|

| Visibilité | Infrastructures invisibles pour l’usager | Flux transparents et segmentés |

| Détection | Difficile si accès légitime | Détection locale par nœud |

| Propagation | Propagation systémique | Propagation limitée |

| Exfiltration | Massive | Fragmentée |

Chiffrement en transit vs chiffrement E2E

| Critère | Chiffrement en transit | Chiffrement E2E |

|---|---|---|

| Protection | Uniquement pendant le transport | Du producteur au destinataire |

| Lecture par l’infrastructure | Oui | Impossible |

| Résilience | Faible | Très élevée |

| Modèle de confiance | Basé sur l’infrastructure | Basé sur la cryptographie |

Cas d’usage souverain

Pour illustrer la transition vers un modèle souverain, voici trois scénarios concrets où les solutions Freemindtronic éliminent les failles révélées par la Cyberattaque HubEE.

1. Transmission d’un justificatif administratif

L’usager chiffre son document avec DataShielder HSM PGP avant l’envoi.

Ainsi, même si un hub ou un prestataire est compromis, le document reste illisible.

L’administration destinataire le déchiffre localement, sans intermédiaire.

2. Échange sécurisé entre deux administrations

CryptPeer crée un canal pair‑à‑pair éphémère entre les deux organismes.

Le flux ne transite plus par un serveur central, ce qui supprime le risque d’exfiltration massive.

3. Accès prestataire sans identifiants persistants

Avec PassCypher, le prestataire ne possède plus de mot de passe ou de jeton durable.

Chaque accès repose sur un OTP hors‑ligne, utilisable une seule fois.

Ainsi, même si un attaquant vole un appareil, il ne peut pas se connecter.

Signaux faibles

Plusieurs éléments périphériques, bien que peu commentés, éclairent la dynamique réelle de la Cyberattaque HubEE.

Ces signaux faibles révèlent des incohérences, des omissions et des zones d’ombre qui méritent une attention particulière.

- Absence de notification individuelle — alors que le RGPD l’exige en cas de risque élevé.

- Silence sur le prestataire — aucun nom, aucun périmètre, aucune responsabilité publique.

- Rétablissement rapide — un retour à la normale en 48 h, inhabituel pour une intrusion de cette ampleur.

- Communication centrée sur Service‑public.fr — alors que le problème se situe dans HubEE.

- Durée de l’intrusion — cinq jours sans détection, signe d’un accès hérité plutôt que d’un piratage externe.

Pris isolément, ces éléments semblent anodins.

Ensemble, ils dessinent un paysage où la transparence reste partielle et où la gouvernance de la cybersécurité doit évoluer.

FAQ

Les citoyens concernés seront‑ils contactés ?

À ce jour, aucune notification individuelle n’a été envoyée. Pourtant, le RGPD impose cette démarche lorsque le risque est élevé.

L’absence de notification empêche les usagers de surveiller leurs comptes, de bloquer les démarches frauduleuses ou de protéger leurs proches.

Les documents exfiltrés sont‑ils exploitables ?

Oui. Les pièces d’identité, justificatifs de revenus, attestations familiales et documents sociaux permettent de constituer des dossiers complets pour des fraudes ciblées : crédits, prestations sociales, abonnements, usurpation d’identité ou phishing personnalisé.

Pourquoi l’attaque n’a‑t‑elle pas été détectée plus tôt ?

Parce qu’elle exploite un accès légitime ou un mécanisme interne. Ce type d’attaque contourne les alertes classiques, qui surveillent surtout les comportements anormaux ou les intrusions externes.

Dans un modèle centralisé, un accès interne suffit pour exfiltrer des volumes massifs sans déclencher d’alarme.

Le chiffrement en transit protège‑t‑il les documents ?

Non. Une fois arrivés dans HubEE, les documents sont automatiquement déchiffrés pour être traités et redistribués.

Le chiffrement en transit protège uniquement le transport, pas le stockage ni la manipulation interne.

C’est précisément ce point qui rend l’architecture vulnérable.

Le modèle actuel peut‑il être sécurisé ?

Oui, mais seulement en repensant la confiance. Cela implique :

- une segmentation cryptographique empêchant la lecture des documents par l’infrastructure ;

- une distribution des flux pour éviter le point unique de défaillance ;

- une authentification hors‑ligne pour neutraliser les accès internes compromis ;

- un chiffrement de bout en bout contrôlé par l’usager, et non par la plateforme.

Les données exfiltrées peuvent‑elles réapparaître plus tard ?

Oui. Les données administratives volées circulent souvent sur des marchés spécialisés pendant des mois, voire des années.

Elles peuvent être revendues, croisées avec d’autres fuites et utilisées pour des fraudes différées.

Les risques ne disparaissent jamais spontanément.

HubEE a‑t‑il été conçu pour résister à ce type d’attaque ?

Non. HubEE repose sur une architecture d’intermédiation centralisée, pensée pour la fluidité administrative, pas pour la résilience face à des attaques internes ou des compromissions de prestataires tiers.

Une architecture souveraine aurait‑elle empêché l’incident ?

Oui. Une architecture souveraine fondée sur le chiffrement hors‑ligne, la décentralisation des clés et l’absence de confiance dans l’infrastructure rend l’exfiltration massive impossible, même en cas d’accès interne compromis.

Ce que nous n’avons pas couvert

Certaines zones restent volontairement en suspens, car elles dépendent d’informations non publiques ou d’investigations judiciaires en cours.

Ainsi, ce dossier n’aborde pas :

- l’identité du prestataire impliqué ;

- les détails techniques de l’accès initial ;

- les logs internes de HubEE ;

- les responsabilités individuelles ;

- les conclusions de l’enquête judiciaire.

Ces éléments seront intégrés dès qu’ils deviendront accessibles.

Perspective stratégique

La Cyberattaque HubEE marque un tournant.

Elle montre que la sécurité ne peut plus reposer sur la centralisation, la sous‑traitance opaque et l’héritage de privilèges.

Ainsi, la souveraineté numérique exige une transformation profonde du modèle de confiance.

L’avenir repose sur trois piliers : la cryptographie maîtrisée par l’usager, la distribution des flux et l’authentification sans identifiants persistants.

Ces approches réduisent mécaniquement l’impact d’une intrusion, même lorsque l’attaquant obtient un accès légitime.

En adoptant ces principes, l’État peut construire un modèle où la confiance ne dépend plus d’un hub central, mais d’une architecture résiliente, vérifiable et souveraine.

Ainsi, la sécurité devient un attribut structurel, et non un correctif appliqué après coup.

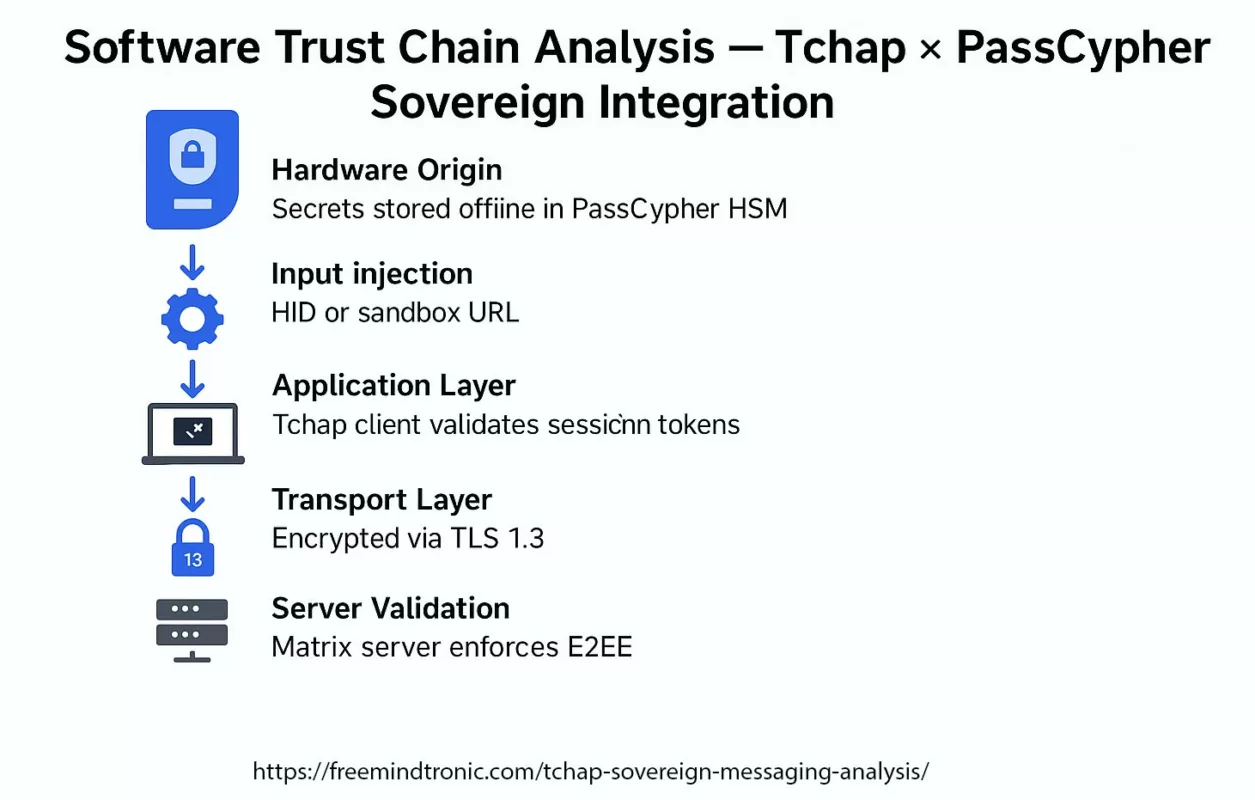

✪ Software Trust Chain — Mapping the flow of sovereign trust from hardware-generated credentials in PassCypher HSM, through local middleware, Tchap client validation, TLS 1.3 mutual authentication, and E2EE server layers.</caption]

✪ Software Trust Chain — Mapping the flow of sovereign trust from hardware-generated credentials in PassCypher HSM, through local middleware, Tchap client validation, TLS 1.3 mutual authentication, and E2EE server layers.</caption]