Individual Digital Sovereignty — as an ethical and technical foundation of informational self-determination, this concept reshapes the current balance between state power, data-driven economies, and cognitive autonomy. At the intersection of law, philosophy, and cybersecurity, this chronicle examines how the Freemindtronic doctrine articulated by Jacques Gascuel conceives individual digital sovereignty as a concrete right: the capacity for individuals to govern themselves within an interconnected digital environment. This approach aligns with contemporary anglophone research on digital self-determination and actor-level digital sovereignty, as discussed in international academic and policy frameworks.

Executive Summary — Key Takeaways

This chronicle defines individual digital sovereignty as a non-delegable operational capability — technical, cognitive, and legal. It exists only when it is locally provable; without material and technical proof, any proclaimed sovereignty remains theoretical.

-

Establishing non-delegable sovereignty as a foundational principle

Principle: First and foremost, individual digital sovereignty constitutes a transnational and strictly non-delegable requirement. Individuals exercise it directly through their ability to govern themselves in digital space, deliberately excluding institutional dependency, cloud-based trust delegation, and algorithmic capture mechanisms.

-

Bridging political theory and operational sovereignty

Conceptual foundations: Over time, institutional and academic research has increasingly converged on a shared conclusion: digital sovereignty cannot be reduced to data protection alone. According to Annales des Mines (2023), sovereignty rests on autonomous and secure control over digital interactions. In parallel, liberal political theory, as articulated by Pierre Lemieux, places individual sovereignty prior to any collective authority. Furthermore, from a legal-performative standpoint, Guillermo Arenas demonstrates how technical architectures and interfaces frequently confiscate sovereignty through invisible norms.Building on this, the Weizenbaum Institute conceptualizes digital sovereignty as an actor’s concrete capacity to shape and control digital environments. Crucially, this framework differentiates infrastructural power from actor-level sovereignty, thereby grounding individual digital sovereignty as a measurable capability rather than a political abstraction. In the broader anglophone academic landscape, normative debates also question the desirability and scope of digital sovereignty at the individual level. As argued by Braun (2024), individual sovereignty in digital environments becomes legitimate only when it preserves agency without reproducing centralized power structures. This perspective reinforces the need for sovereignty grounded in capability rather than declaration.

-

Shifting trust from delegation to local proof

Technical convergence: In practice, major anglophone cybersecurity frameworks now partially converge on the same operational insight. On the one hand, the ENISA Threat Landscape 2024 explicitly emphasizes the necessity of local trust anchors. On the other hand, NIST SP 800-207 (Zero Trust Architecture) reframes trust as a continuously verified state rather than a condition granted by default. Together, these approaches validate the principle of local technical proof

, which lies at the core of the Freemindtronic doctrine.Moreover, recent academic analysis reinforces this convergence. In a critical evaluation of existing models, Fratini (2024) demonstrates that most digital sovereignty frameworks remain declarative and institution-centric, as they lack operational mechanisms for individual-level proof. Consequently, this gap aligns directly with the Freemindtronic position, which treats sovereignty as provable by design. Finally, from an engineering perspective, research published by the IEEE Computer Society further confirms the centrality of local proof and Zero Trust validation mechanisms at the system level.

-

Reducing legal exposure through architectural absence

Legal developments: At the international level, lawmakers and courts increasingly converge on a similar logic. Regulation (EU) 2023/1543 (e-Evidence), together with the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (Tele2/Watson), reinforces a key principle also recognized in anglophone legal scholarship: when systems retain no data, they structurally reduce legal exposure. As a result, this evolution directly supports the logic of compliance by absence, already established in GDPR-oriented doctrine.

-

Positioning individual sovereignty as a democratic resilience factor

Democratic stakes: Beyond privacy considerations, individual digital sovereignty actively conditions democratic resilience itself. To that end, it requires cognitive autonomy to resist algorithmic influence, technical autonomy to select and modify tools independently, and legal autonomy to secure rights without reliance on centralized or revocable guarantees.

-

Advancing toward an integrated sovereignty framework

Perspective: Finally, from the EU General Data Protection Regulation to recent national cybersecurity statutes, legal frameworks continue to expand. Nevertheless, they remain fragmented and often reactive. Only an approach that deliberately integrates law, system design, and cognition can restore a durable balance between individual freedom and collective security.

When Not to Intervene Destructively — Sovereign Stop Condition

When the chain of trust is already compromised (proven intrusion, espionage, secret exfiltration, imposed dependency on KMS, IAM, or IDP services), uncontrolled attempts to “regain control” may worsen exposure and destroy evidentiary value. In such states, the sovereign decision is not inaction but halting irreversible actions: isolate, document, preserve states, and refrain from changes that would compromise technical, legal, or operational proof.

Irreversible Boundary

Once a critical secret (master key, cryptographic seed, authentication token) has been generated, stored, or transited through non-sovereign hardware or infrastructure, its trust level cannot be retroactively restored. No software patch, regulatory reform, or contractual framework can reverse this condition. This boundary is material and cryptographic, not procedural.

Reading Parameters

Executive Summary: ≈ 1 min

Advanced Summary: ≈ 4 min

Full Chronicle: ≈ 40 min

Publication date: 2025-11-10

Last updated: 2025-11-10

Complexity level: Doctrinal & Transdisciplinary

Technical density: ≈ 74%

Available languages: FR · EN · ES · CAT · AR

Thematic focus: Sovereignty, autonomy, cognition, digital law

Editorial format: Chronicle — Freemindtronic Cyberculture Series

Strategic impact level: 8.2 / 10 — epistemological and institutional

☰ Quick Navigator

- 🔝Back to top

- Executive Summary

- Advanced Summary

- Chronicle Core

- Trusted Third Parties

- Legal Extraterritoriality

- Key Custody and Sovereignty

- Typology of Individual Digital Sovereignty

- Proven Sovereignty

- Human-Centered Sovereignty

- Doctrinal Validation

- Non-Traceability Doctrine

- Perspectives

- Strategic Outlook

- Perspectives — 2026 and Beyond

- Doctrinal FAQ

- What We Did Not Cover

Advanced Summary — Foundations, Tensions, and Doctrinal Frameworks

According to Annales des Mines (2023), individual digital sovereignty refers to the capacity of individuals to exercise autonomous and secure control over their data and their interactions in the digital space. This institutional definition goes beyond data protection alone: it presupposes mastery of tools, understanding of protocols, and awareness of algorithmic capture risks. Comparable definitions also emerge in anglophone academic work, where digital sovereignty is increasingly framed as an actor’s capacity to shape and control digital environments rather than merely protect data.

Institutional Definition — Annales des Mines (2023)

“Individual digital sovereignty refers to the capacity of individuals to exercise autonomous and secure control over their data and their interactions in the digital space.”

It implies:

- Autonomy and security: digital competencies, data protection, risk mastery;

- Tools and technologies: encryption, open-source software, blockchain as empowerment levers;

- Communities and practices: ecosystems fostering privacy and distributed autonomy.

From a liberal perspective, Pierre Lemieux frames individual sovereignty as a last-instance power: it precedes the state, the law, and any form of collective authority. The individual, not society, is the original holder of power. Formulated in 1987, this principle anticipates contemporary debates on decentralization and distributed governance.

For Pauline Türk (Cairn.info, 2020), digital sovereignty first emerged as a contestation of state power by multinational digital actors. Over time, this tension shifted toward users, who carry a right to informational self-determination (a concept widely discussed in anglophone legal and ethical scholarship). The individual becomes an actor—not a spectator—in protecting data and governing digital identities.

Contemporary Normative Frameworks — Toward Proven Sovereignty

Recent cybersecurity frameworks confirm the doctrinal shift underway:

- Report No. 4299 (French National Assembly, 2025) — acknowledges the need for a trust model grounded in technical proof and local mastery rather than external certification alone.

- ENISA Threat Landscape 2024 — introduces the notion of a local trust anchor: resilience is measured by a device’s capacity to operate without cloud dependency.

- NIST SP 800-207 (Zero Trust Framework) — turns trust into a provable dynamic state, not a granted status; each entity must demonstrate legitimacy at every interaction.

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1543 “e-Evidence” and CJEU Tele2/Watson — legally reinforce the logic of compliance by absence: where no data is stored, sovereignty remains structurally less exposable.

These evolutions reinforce the Freemindtronic doctrine: local proof becomes a primary condition for any digital trust—individual, state, or interoperable.

Finally, Guillermo Arenas (2023) advances a legal and performative reading: sovereignty exists only because it is stated and recognized through normative discourse. In the digital domain, this recognition is often confiscated by technical architectures and interfaces that impose invisible rules and produce sovereignty effects without democratic legitimacy. The question becomes: how can individual sovereignty be instituted without a state, inside a hegemonic technical environment?

Doctrinal Frameworks — Comparative Table

| Doctrinal framework | Concept of sovereignty | Mode of exercise | Type of dependency | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pierre Lemieux (1987) | Radical, non-transferable sovereignty | Rejection of any delegation; absolute individual autonomy | Social and institutional | Lemieux (1987) Weizenbaum Institute — Digital Sovereignty (EN) |

| Pauline Türk (2020) | Informational self-determination | User re-appropriation of data and digital identity | Economic and normative | Türk (2020) Verfassungsblog — Digital Sovereignty & Rights (EN) |

| Guillermo Arenas (2023) | Performative sovereignty | Institution of individual norms through legal and technical practices | Technical and symbolic | Arenas (2023) Fratini — Digital Sovereignty Models (Springer, EN) |

| Institutional frameworks (EU / ENISA, 2024) | Sovereignty grounded in choice and accountability | Coordination, responsibility, and operational resilience | Legal and political | French Council of State (2024) ENISA — Threat Landscape 2024 (EN) |

1️⃣ law (to protect and define),

2️⃣ technology (to design and secure),

3️⃣ cognition (to understand and resist).

Its effectiveness depends on the convergence of these three dimensions—now partially reconciled through normative recognition of local proof of trust (ENISA, NIST, Report 4299). Without this convergence, individuals remain administered by architectures they can neither verify nor contest.

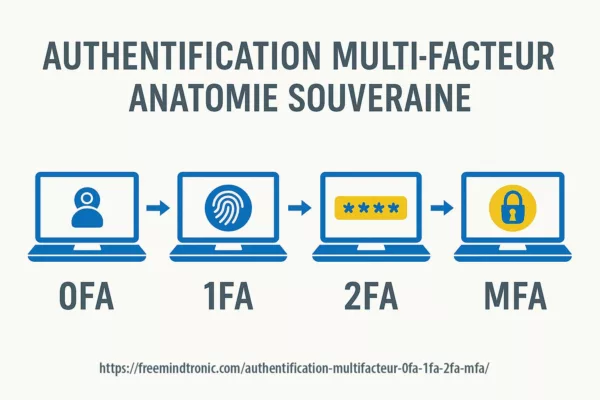

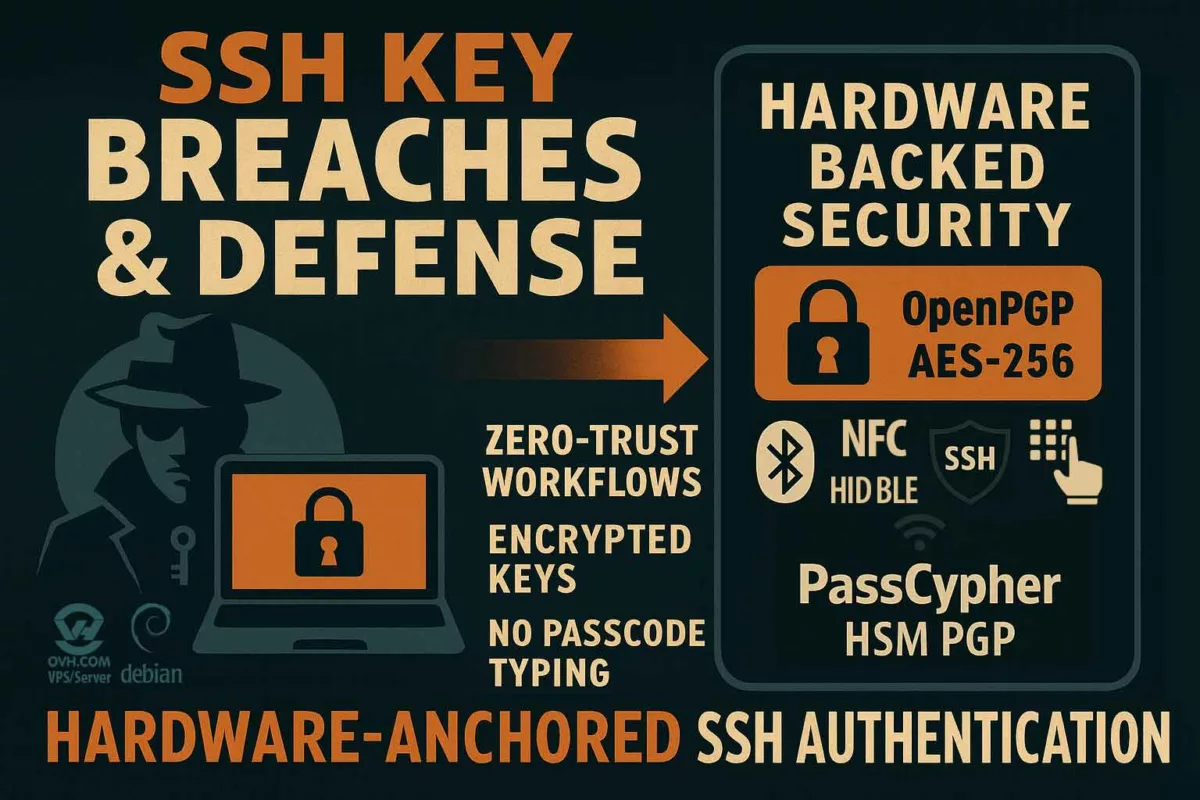

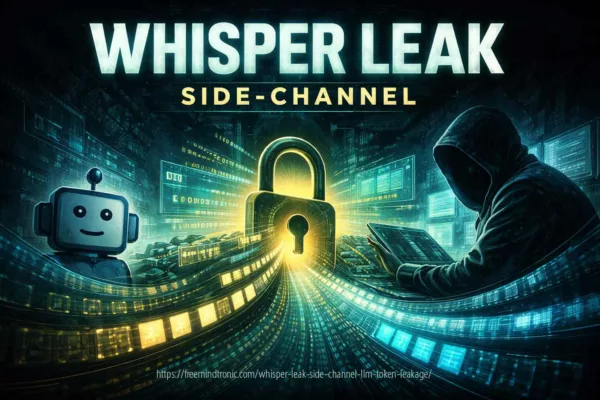

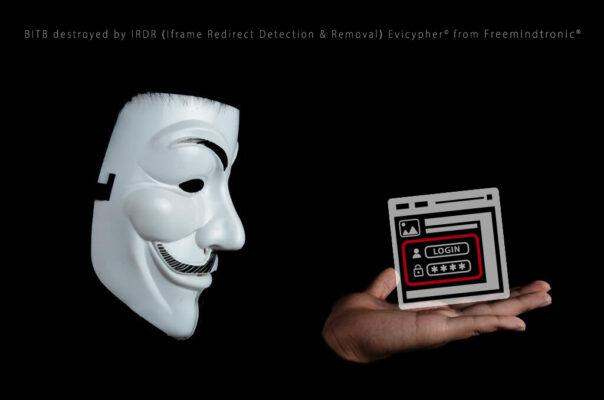

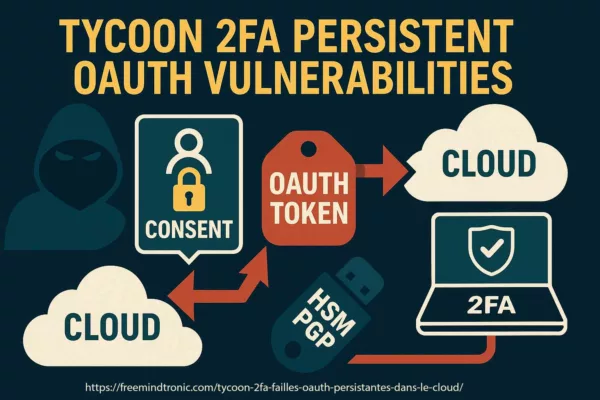

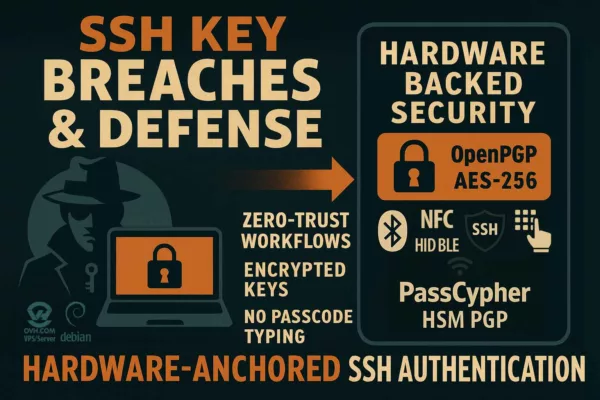

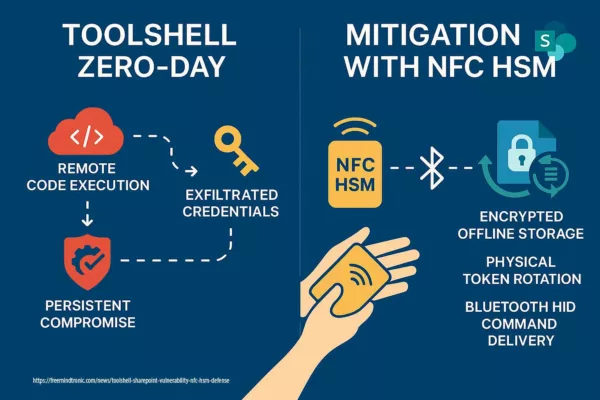

The chronicles displayed above ↑ belong to the same Cyberculture editorial series. They extend the reflection on the epistemological and technical foundations of digital sovereignty, by exploring its legal, cognitive, and cryptographic dimensions. This selection complements the present chronicle devoted to individual digital sovereignty — a central concept of the Freemindtronic doctrine, which articulates technical autonomy, cognitive autonomy, and legal autonomy within the connected world.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary — Key Takeaways

- Advanced Summary — Foundations, Tensions, and Doctrinal Frameworks

- Chronicle — Autonomy, Cognition, and Individual Digital Sovereignty

- The Trusted Third-Party Model — Origins, Limits, and Rupture

- Legal Extraterritoriality — When Foreign Law Imposes Itself on Individual Sovereignty

- Is Your Individual Digital Sovereignty Really in Your Hands?

- Typology of Individual Digital Sovereignty Dimensions

- Proven Sovereignty — Patents and Embodied Doctrines

- The Human at the Center of Individual Sovereignty

- Doctrinal Validation — Institutional Recognition

- Doctrine of Sovereign Non-Traceability

- Critical Perspectives — Resistance and Cognitive Autonomy

- Strategic Outlook — Horizon 2030

- Perspectives — 2026 and Beyond

- Doctrinal FAQ

Chronicle — Autonomy, Cognition, and Individual Digital Sovereignty

This chronicle explores the foundational tension between individual autonomy, cognition, and digital power. It demonstrates that individual digital sovereignty cannot be declared: it must be exercised, proven, and embodied in material, cognitive, and legal systems. The approach is deliberately transdisciplinary, connecting political philosophy, law, cybernetics, and sovereign technologies in order to analyze the concrete conditions of informational self-determination. It establishes a doctrine rather than a method and explicitly assumes its limits.

Individual digital sovereignty — foundations, tensions, and global perspectives. This chronicle considers individual sovereignty as a transnational, non-delegable, and non-representable requirement. It examines how individuals can reclaim effective control over their decision-making capacities within a digital environment dominated by architectures of control, normalization, and technical delegation.

From this point onward, any attempt at uncontrolled optimization or remediation without local proof of control (secrets, dependencies, traces) is discouraged. Continuing to act in an unproven state increases exposure and may irreversibly compromise the technical or legal value of observable elements.

Software can organize trust, but it cannot override a material decision. A compromised key, an imposed firmware, an unaudited enclave, or an observed channel remain physical realities. Material reality always prevails over software intent.

Expanded definition of individual sovereignty

A concept at the intersection of law, technology, and cognition.

Institutional framework — A capability-based definition

According to Annales des Mines, “individual digital sovereignty refers to the capacity of individuals to exercise autonomous and secure control over their data and interactions in digital space.” Formulated within an institutional framework, this definition aligns with the critical approaches developed in this chronicle. It emphasizes three fundamental dimensions: technical autonomy, information security, and cognitive resistance to algorithmic capture.

A capability recognized by an institution is not equivalent to a capability effectively held. Sovereignty begins where delegation ends.

Philosophical framework — Self-governance

From a philosophical standpoint, individual sovereignty is defined as the capacity of an individual to govern themselves. It implies control over one’s thoughts, choices, data, and representations. This power forms the foundation of any authentic freedom. Indeed, it presupposes not only the absence of interference but also the mastery of the material and symbolic conditions of one’s existence. Consequently, control over infrastructure, code, and cognition becomes a direct extension of political freedom.

Liberal framework — Pierre Lemieux and ultimate authority

For Pierre Lemieux, individual sovereignty constitutes an ultimate authority. It precedes the State, law, and any collective power. The individual is not administered; they are the primary source of all norms. Formulated as early as 1987, this principle already anticipated the crisis of centralization and foreshadowed the emergence of distributed governance models. Today, the data economy merely displaces the question of power — between those who govern flows and those who understand them.

Informational framework — Pauline Türk and self-determination

From a complementary perspective, Pauline Türk shows that digital sovereignty initially emerged as a challenge to State power by major platforms. Over time, it shifted toward users, who carry a right to informational self-determination. As a result, sovereignty no longer appears as a fixed legal status but as a cognitive competence: knowing when, why, and how to refuse.

Performative framework — Guillermo Arenas and enacted sovereignty

Finally, Guillermo Arenas proposes a performative reading according to which sovereignty exists only because it is articulated, recognized, and practiced. In digital environments, this performativity is often captured by technical architectures — interfaces, APIs, and algorithms. These systems produce sovereign effects without democratic legitimacy. Consequently, the central question becomes: how can individual sovereignty be instituted without the State, yet with technical integrity?

⮞ Essential finding

— Individual digital sovereignty does not stem from ownership but from an operational capability. It results from the convergence of three spheres: law, which defines and protects; technology, which designs and controls; and cognition, which understands and resists. When these dimensions align, sovereignty ceases to be an abstraction and becomes a real, measurable, and enforceable power.

Design framework — Freemindtronic and proven sovereignty

From this perspective, digital autonomy is not a utopia. It is grounded in concrete conditions of existence: understanding mechanisms, transforming them, and refusing imposed dependencies. It is within this space of constructive resistance that the Freemindtronic doctrine situates its approach. It chooses to demonstrate sovereignty through design rather than proclaim it by decree.

⚖️ Definition by Jacques Gascuel — Individual Digital Sovereignty

Individual digital sovereignty refers to the exclusive, effective, and measurable power held by each individual (or small team) to design, create, hold, use, share, and revoke their secrets, data, and representations in digital space — without delegation, without trusted third parties, without exposure of identities or metadata, and without persistent traces imposed by external infrastructure.

It introduces a form of personal cryptographic governance, in which sovereignty becomes an operational, reversible, and enforceable capability. This principle rests on the unification of three inseparable spheres:

- law, which protects and defines;

- technology, which designs and secures;

- cognition, which understands and resists.

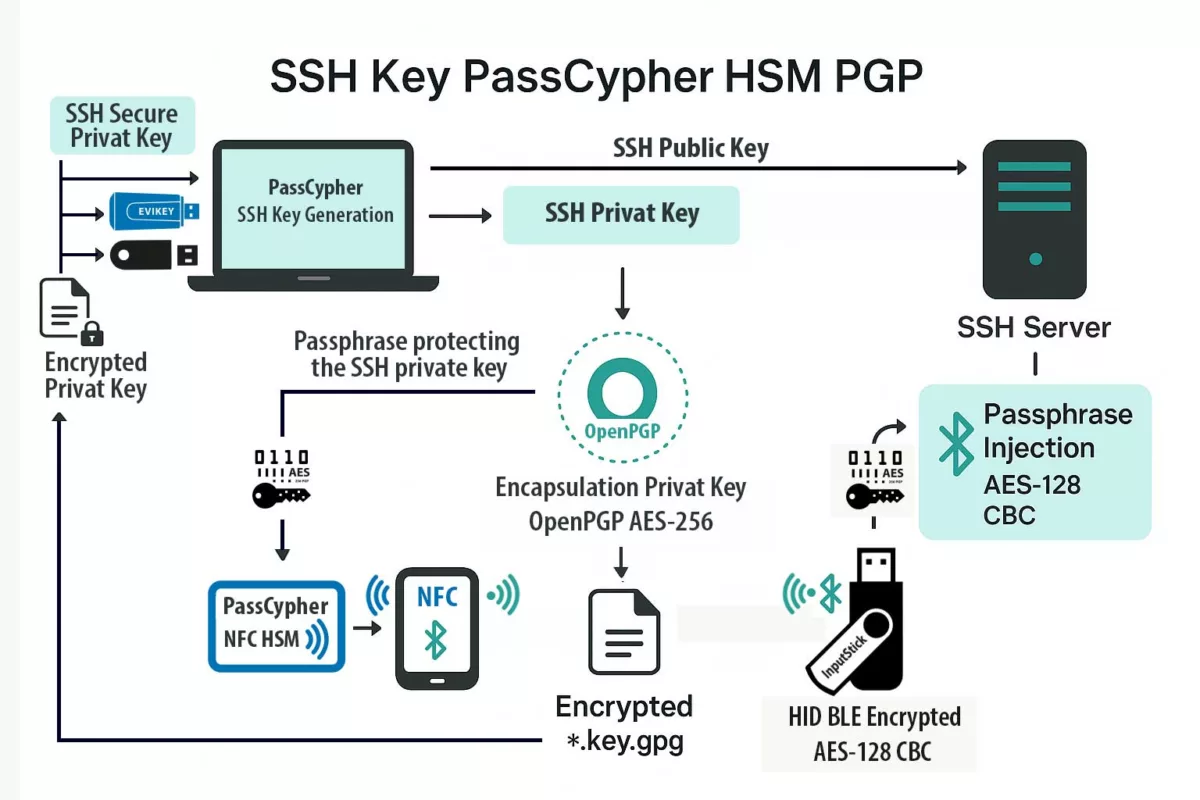

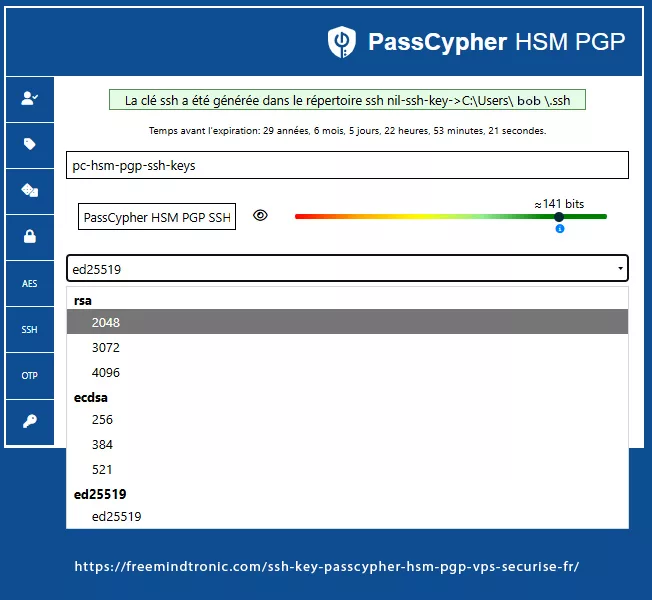

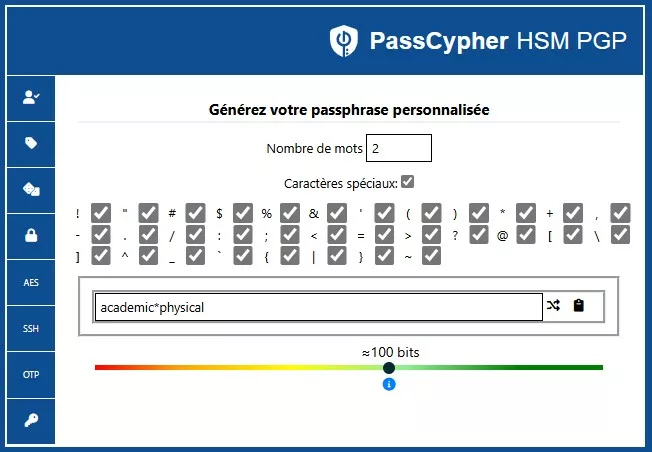

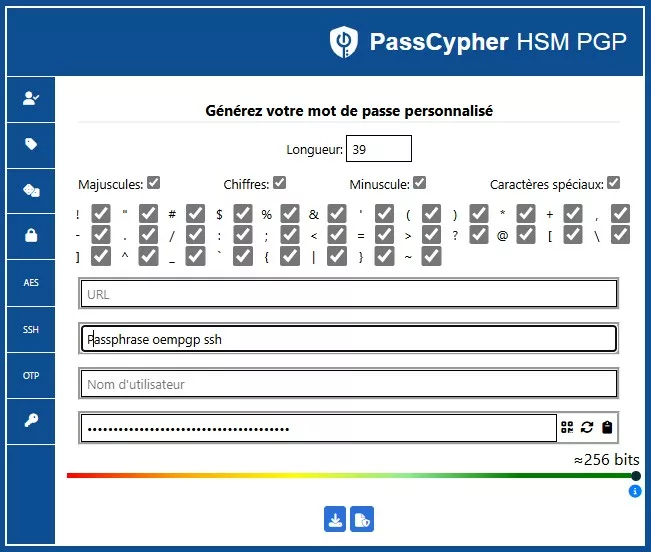

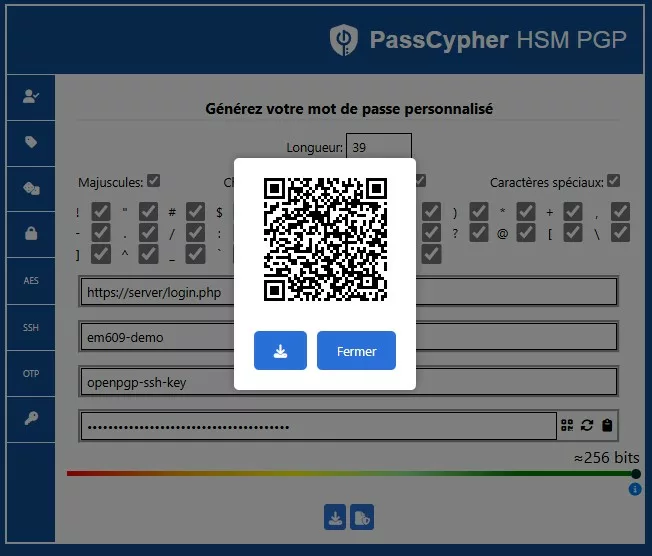

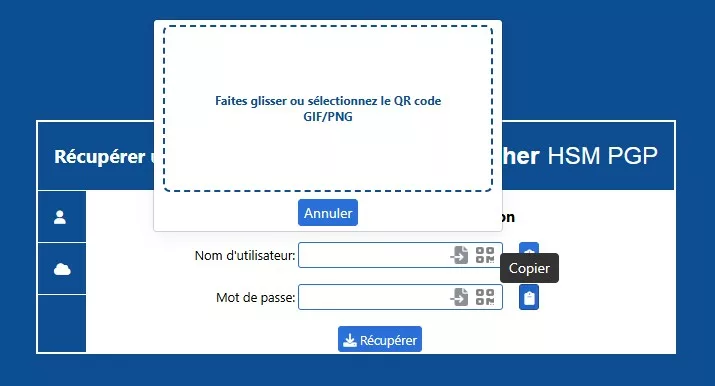

It constitutes the conceptual foundation of Freemindtronic technologies such as:

- 🔐 PassCypher

- 🔐 DataShielder

- 🔐 CryptPeer

This institutional requirement also resonates with Report No. 4299 of the French National Assembly, entitled “Building and Promoting National and European Digital Sovereignty”, presented by Jean-Luc Warsmann and Philippe Latombe. Although issued within a national parliamentary framework, this report explicitly acknowledges the need for non-dependent digital devices compatible with principles of non-traceability

and self-custody. It thus provides an institutional validation of sovereignty models that do not rely on centralized trust infrastructures or mandatory data retention. Download the report (PDF).

The Trusted Third-Party Model — Origins, Limits, and Rupture

The origin of a delegation-based model

Historically, the concept of a trusted third party emerged in the analog world through notaries, banks, certification authorities, and public institutions. As digital systems expanded, this logic migrated almost seamlessly into the digital realm. Consequently, trust became centralized through authentication servers, certified clouds, and so-called “sovereign platforms.” At its core, this model rests on a simple assumption: security requires delegation.

However, this assumption directly conflicts with the very notion of individual digital sovereignty. By delegating trust, individuals inevitably delegate part of their decision-making power. In doing so, they renounce a portion of their digital freedom. As a result, when security resides in the hands of third parties, users gradually shift from sovereign actors to administrated entities.

The structural crisis of centralization

Over the past two decades, repeated large-scale breaches have exposed the fragility of delegation-based security. Incidents such as Equifax, SolarWinds, MOVEit, LastPass, and Microsoft Exchange have demonstrated a systemic pattern: the more secrets concentrate in a single repository, the more likely their compromise becomes. Centralization therefore amplifies risk rather than mitigating it.

Accordingly, reference frameworks increasingly challenge implicit trust models. Both the ENISA Threat Landscape 2024 and NIST SP 800-207 (Zero Trust Architecture) reposition local technical proof at the core of resilience. Centralized trust now appears not as a safeguard, but as a structural vulnerability.

When centralized systems fail

At this point, two distinct failure paths emerge. First, illegitimate compromise—through intrusion, vulnerability exploitation, HSM compromise, API leakage, or CI/CD artifact theft—creates systemic risk. A single breach propagates across all delegated users. Attribution becomes disputable, non-repudiation weakens, logs may be altered, and mass revocation processes trigger probative denial of service.

Second, legitimate compromise—via judicial orders, emergency access clauses, key escrow mechanisms, or privileged KMS administration—introduces a different threat: legal capture. Even without wrongdoing, individuals remain exposed because they no longer hold exclusive control over their secrets.

In both scenarios, centralization creates a single point of inflection. Delegation silently reverses the practical burden of proof and shifts responsibility onto users, who must justify actions they may never have directly controlled.

By contrast, when architectures invert this logic—placing keys with users, enforcing local proof, and eliminating persistent traces—attacks lose scalability. Trust no longer rests on presumption; instead, it becomes opposable by design.

Legal Extraterritoriality — When Foreign Law Overrides Individual Sovereignty

Extraterritorial law as a structural constraint

In digital environments, legal authority no longer stops at national borders. On the contrary, extraterritorial laws increasingly project foreign jurisdiction onto infrastructures, service providers, and even end users. As a result, individuals may remain subject to legal obligations imposed by jurisdictions they neither reside in nor consent to. This dynamic directly challenges the principle of individual digital sovereignty.

For instance, legislation such as the U.S. CLOUD Act or similar cross-border data access mechanisms allows authorities to compel service providers to disclose data stored abroad. Consequently, sovereignty becomes conditional, not on the individual’s actions, but on the legal exposure of the intermediary they depend on. In practice, delegation once again translates into loss of control.

From legal cooperation to legal capture

Initially, extraterritorial mechanisms aimed to facilitate judicial cooperation in criminal investigations. However, over time, they evolved into permanent access channels embedded within digital infrastructures. Therefore, even lawful users operating in good faith remain exposed. The risk does not stem from misuse, but from structural compliance obligations imposed on intermediaries.

Moreover, when cryptographic keys, identity services, or authentication systems rely on third-party providers, legal compulsion silently bypasses user consent. At that point, the individual no longer negotiates sovereignty with the State directly. Instead, it is transferred upstream, where compliance prevails over autonomy. Thus, legal extraterritoriality becomes an invisible vector of dependency.

The asymmetry between legal power and technical agency

Crucially, law operates asymmetrically. While individuals remain bound by territorial legal systems, cloud providers and digital platforms operate transnationally. As a consequence, legal power scales globally, whereas individual agency remains local. This imbalance erodes the practical enforceability of rights such as confidentiality, secrecy of correspondence, and control over personal data.

Furthermore, even when legal safeguards exist, they often rely on post hoc remedies. Yet, once data is disclosed or keys are accessed, sovereignty cannot be retroactively restored. Therefore, protection through legal means alone proves insufficient. Without architectural measures, law reacts after the fact, whereas sovereignty requires prevention by design.

Architectural resistance as a condition of sovereignty

For this reason, individual digital sovereignty cannot depend solely on regulatory guarantees. Instead, it requires architectural resistance to extraterritorial capture. When individuals retain exclusive control over their cryptographic material and operate systems that produce no exploitable traces, legal coercion loses effectiveness. There is nothing to request, nothing to seize, and nothing to compel.

Accordingly, sovereignty shifts from a legal status to an operational condition. Rather than opposing law, this approach complements it by limiting exposure at the technical level. In doing so, it restores symmetry between legal authority and individual agency.

Is the Key to Your Digital Sovereignty Really in Your Hands?

The illusion of key ownership

At first glance, many digital services claim to offer user-controlled encryption. However, in practice, this control often remains partial or conditional. For example, when keys are generated, stored, backed up, or recoverable through external services, sovereignty immediately weakens. Although users may initiate cryptographic operations, they rarely control the entire key lifecycle.

Moreover, cloud-based key management services, identity providers, and hardware-backed enclaves frequently embed administrative override mechanisms. As a result, what appears as ownership becomes licensed usage. The user operates within predefined constraints, while the provider retains ultimate authority. Consequently, sovereignty dissolves into permission.

Delegation embedded in key management architectures

Beyond explicit key escrow, delegation often hides within architecture itself. Centralized KMS, remote HSMs, federated IAM systems, and recovery workflows systematically reintroduce third-party control. Even when access remains technically restricted, operational dependence persists. Therefore, the individual no longer controls when, how, or under which conditions keys may be accessed or revoked.

Furthermore, compliance requirements, audit interfaces, and automated logging mechanisms generate persistent metadata. These traces, although presented as security features, effectively reconstruct user activity. In doing so, they transform cryptographic protection into a surveillance-compatible system. Thus, sovereignty erodes not through failure, but through design.

Self-custody as a non-negotiable condition

In contrast, self-custody redefines sovereignty as an exclusive capability. When individuals generate, store, use, and revoke keys locally, without external dependency, they reclaim full control over cryptographic authority. Importantly, self-custody does not merely reduce risk; it changes the trust model entirely. Trust no longer relies on promises, certifications, or contractual assurances. Instead, it rests on verifiable absence of delegation.

Additionally, local key custody limits the scalability of attacks. Without centralized repositories, attackers lose leverage. Legal coercion also loses effectiveness, since no intermediary holds exploitable material. Therefore, sovereignty becomes enforceable through architecture rather than policy.

From possession to governance

Finally, sovereignty over keys is not only about possession, but about governance. Individuals must retain the ability to define usage contexts, expiration conditions, and revocation triggers. They must also understand the implications of each design choice. Consequently, cryptographic sovereignty extends into cognitive sovereignty: knowing when to trust, when to refuse, and when to stop.

When keys remain local, ephemeral, and context-bound, sovereignty ceases to be symbolic. It becomes operational, reversible, and defensible.

Is the Key to Your Digital Sovereignty Really in Your Hands?

The illusion of key ownership

At first glance, many digital services claim to offer user-controlled encryption. However, in practice, this control often remains partial or conditional. For example, when keys are generated, stored, backed up, or recoverable through external services, sovereignty immediately weakens. Although users may initiate cryptographic operations, they rarely control the entire key lifecycle.

Moreover, cloud-based key management services, identity providers, and hardware-backed enclaves frequently embed administrative override mechanisms. As a result, what appears as ownership becomes licensed usage. The user operates within predefined constraints, while the provider retains ultimate authority. Consequently, sovereignty dissolves into permission.

Delegation embedded in key management architectures

Beyond explicit key escrow, delegation often hides within architecture itself. Centralized KMS, remote HSMs, federated IAM systems, and recovery workflows systematically reintroduce third-party control. Even when access remains technically restricted, operational dependence persists. Therefore, the individual no longer controls when, how, or under which conditions keys may be accessed or revoked.

Furthermore, compliance requirements, audit interfaces, and automated logging mechanisms generate persistent metadata. These traces, although presented as security features, effectively reconstruct user activity. In doing so, they transform cryptographic protection into a surveillance-compatible system. Thus, sovereignty erodes not through failure, but through design.

Self-custody as a non-negotiable condition

In contrast, self-custody redefines sovereignty as an exclusive capability. When individuals generate, store, use, and revoke keys locally, without external dependency, they reclaim full control over cryptographic authority. Importantly, self-custody does not merely reduce risk; it changes the trust model entirely. Trust no longer relies on promises, certifications, or contractual assurances. Instead, it rests on verifiable absence of delegation.

Additionally, local key custody limits the scalability of attacks. Without centralized repositories, attackers lose leverage. Legal coercion also loses effectiveness, since no intermediary holds exploitable material. Therefore, sovereignty becomes enforceable through architecture rather than policy.

From possession to governance

Finally, sovereignty over keys is not only about possession, but about governance. Individuals must retain the ability to define usage contexts, expiration conditions, and revocation triggers. They must also understand the implications of each design choice. Consequently, cryptographic sovereignty extends into cognitive sovereignty: knowing when to trust, when to refuse, and when to stop.

When keys remain local, ephemeral, and context-bound, sovereignty ceases to be symbolic. It becomes operational, reversible, and defensible.

Proven Sovereignty — From Declaration to Design

Why declarative sovereignty fails

For decades, institutions, platforms, and vendors have proclaimed sovereignty through policies, certifications, and contractual assurances. However, these declarations rarely survive technical scrutiny. In practice, sovereignty that depends on trust statements collapses as soon as architectures introduce hidden dependencies, opaque processes, or privileged access paths.

Moreover, declarative sovereignty places the burden of proof on the individual. Users must trust claims they cannot verify and accept guarantees they cannot audit. Consequently, sovereignty remains symbolic rather than operational. It exists in discourse, not in systems.

Sovereignty as an architectural property

By contrast, proven sovereignty emerges when systems demonstrate their properties through operation. In this model, architecture itself produces proof. If no third party can access keys, then no trust is required. If no telemetry exists, then no data can leak. If no persistent traces remain, then no retrospective exposure is possible.

Therefore, sovereignty shifts from promise to fact. It no longer relies on certification, compliance, or goodwill. Instead, it rests on constraints that systems cannot bypass. In this sense, design becomes law, and architecture becomes evidence.

Proof by design and verifiability

Crucially, proof by design does not require secrecy. On the contrary, it thrives on verifiability. When mechanisms remain simple, local, and inspectable, individuals can verify sovereignty themselves. As a result, trust becomes optional rather than mandatory.

Furthermore, this approach aligns with Zero Trust principles without reproducing their centralized implementations. Verification occurs locally, continuously, and without delegation. Thus, sovereignty remains active rather than static.

Embodied doctrine and operational reality

At this stage, doctrine ceases to be abstract. It becomes embodied through concrete constraints: local key custody, offline-first operation, absence of telemetry, and strict separation of identities. Each constraint removes a class of dependency. Together, they form a coherent sovereignty posture.

Consequently, sovereignty becomes enforceable not through litigation, but through impossibility. What systems cannot do, they cannot be compelled to do. This inversion restores symmetry between individual agency and systemic power.

The Human at the Center of Individual Digital Sovereignty

Sovereignty as an exercised capacity

First and foremost, sovereignty does not reside in tools, devices, or legal texts. Instead, it emerges through human action. Individuals exercise sovereignty when they decide how systems operate, when to engage, and when to stop. Without this active involvement, even technically sovereign architectures lose meaning.

Moreover, sovereignty implies accountability. When individuals retain control over keys, systems, and identities, they also assume responsibility for their choices. Consequently, sovereignty cannot be outsourced without being diluted. Delegation may simplify usage, but it simultaneously transfers decision-making power away from the individual.

Cognitive responsibility and informed refusal

Beyond technical control, sovereignty requires cognitive responsibility. Individuals must understand the implications of their actions, including the limits of remediation. In certain situations, acting further may increase exposure rather than restore control.

Therefore, informed refusal becomes a sovereign act. Choosing not to optimize, not to reconnect, or not to intervene can preserve probative integrity. In this context, inaction does not signal weakness. On the contrary, it reflects an awareness of thresholds beyond which sovereignty degrades.

Stopping conditions as sovereign decisions

In digital environments, systems often encourage continuous action: updates, synchronizations, recoveries, and retries. However, sovereignty requires the ability to define stopping conditions. When trust chains break, further action may contaminate evidence, increase traceability, or escalate dependency.

Accordingly, sovereign systems must allow individuals to freeze states, isolate environments, and cease interactions without penalty. These stopping conditions protect both technical integrity and legal defensibility. Thus, restraint becomes a form of control.

Responsibility without isolation

Finally, placing the human at the center does not imply withdrawal from society. Sovereign individuals can still cooperate, share, and contribute. However, they do so on terms they define. Responsibility remains personal, while interaction remains voluntary.

As a result, sovereignty restores balance. Individuals regain agency without rejecting collective structures. They participate without surrendering control.

Doctrinal Validation — Institutional Recognition and Its Limits

Growing institutional acknowledgment

Over the past decade, institutions have increasingly incorporated digital sovereignty into strategic discourse. Reports issued by national parliaments, regulatory authorities, and international organizations now recognize the risks associated with dependency on centralized infrastructures. As a result, sovereignty has moved from a marginal concern to a policy objective.

However, this recognition often remains abstract. Institutions describe sovereignty in terms of choice, resilience, and autonomy, yet they rarely define the technical conditions required to achieve it. Consequently, acknowledgment does not automatically produce empowerment. Instead, it frequently reinforces existing structures through managed alternatives.

Standards as partial convergence points

In parallel, technical standards increasingly converge toward similar principles. Frameworks such as Zero Trust Architecture emphasize continuous verification, least privilege, and local enforcement. Likewise, cybersecurity agencies highlight the importance of minimizing attack surfaces and reducing implicit trust.

Nevertheless, standards typically assume the presence of intermediaries. They optimize delegation rather than eliminate it. Therefore, while standards improve security posture, they stop short of guaranteeing sovereignty. They mitigate risk without restoring exclusive control.

The gap between recognition and enforceability

Crucially, institutional validation does not equal enforceability. A right recognized without an associated technical capability remains fragile. When sovereignty depends on compliance audits, contractual assurances, or regulatory oversight, it remains revocable.

By contrast, enforceable sovereignty emerges when institutions recognize architectures that make dependency impossible by design. Until then, recognition functions as a signal rather than a guarantee. It confirms intent, not outcome.

Doctrine as a bridge between policy and design

At this intersection, doctrine plays a decisive role. It translates abstract principles into concrete constraints. It identifies where recognition ends and where design must begin. In doing so, doctrine enables institutions to move beyond declarations toward measurable criteria.

Therefore, doctrinal validation does not replace institutional authority. Instead, it equips institutions with a framework to evaluate sovereignty operationally rather than rhetorically.

The Doctrine of Non-Traceability — Sovereignty Through Absence

From traceability to structural exposure

In most digital systems, traceability is presented as a security or accountability feature. Logs, identifiers, telemetry, and audit trails aim to reconstruct actions after the fact. However, while traceability may facilitate incident response, it simultaneously creates persistent exposure. Every retained trace becomes a potential liability.

Consequently, the more a system records, the more it enables reconstruction, correlation, and coercion. Over time, traceability transforms from a defensive mechanism into a vector of control. Thus, systems designed around exhaustive visibility inadvertently undermine individual sovereignty.

Non-traceability as an active design choice

By contrast, non-traceability does not result from negligence or opacity. Instead, it emerges from deliberate architectural decisions. Designers must actively eliminate unnecessary traces, restrict metadata generation, and prevent persistence beyond immediate use. Therefore, non-traceability requires intention, not omission.

Moreover, non-traceable systems do not conceal wrongdoing. Rather, they limit structural overreach. When systems produce no exploitable data, they neutralize both illegitimate intrusion and legitimate over-collection. In this sense, absence becomes protective.

Compliance through absence

Importantly, non-traceability aligns with regulatory principles such as data minimization and proportionality. When systems do not generate data, they cannot misuse it. As a result, compliance shifts from procedural obligations to structural guarantees.

This approach inverts the usual compliance logic. Instead of managing data responsibly, sovereign systems prevent data from existing unnecessarily. Consequently, compliance becomes intrinsic rather than enforced.

Probative volatility and reversibility

Furthermore, non-traceability introduces probative volatility. Evidence exists only as long as it remains locally necessary. Once usage ends, traces disappear. This volatility protects individuals from retrospective interpretation and indefinite exposure.

Additionally, reversibility becomes possible. Individuals can disengage, revoke access, or terminate sessions without leaving residual footprints. Therefore, sovereignty regains temporal boundaries.

Absence as a condition of freedom

Ultimately, non-traceability reframes freedom itself. Freedom no longer depends on oversight or permission, but on the impossibility of surveillance by design. When nothing persists, nothing can be exploited.

Thus, sovereignty through absence does not weaken accountability. Instead, it restores proportionality between action and exposure.

Perspectives — Resistance, Autonomy, and Cognitive Resilience

From technical resistance to systemic resilience

Initially, resistance appears as a technical response to dependency and surveillance. Individuals seek tools that reduce exposure and restore control. However, over time, resistance evolves into resilience. Rather than reacting to each new constraint, sovereign systems anticipate pressure and absorb it structurally.

Consequently, resilience depends less on constant adaptation and more on stable principles. When architectures minimize delegation and traces, they remain robust despite regulatory, economic, or geopolitical shifts. Thus, resistance matures into a durable posture.

Cognitive pressure and behavioral capture

Meanwhile, technical autonomy alone does not neutralize cognitive pressure. Platforms increasingly shape behavior through defaults, recommendations, and subtle nudges. As a result, individuals may retain technical control while gradually losing decisional freedom.

Therefore, cognitive resilience becomes essential. It requires awareness of influence mechanisms and the capacity to disengage from them. Importantly, this resilience does not rely on abstention, but on selective engagement. Individuals choose when to interact and when to refuse.

Autonomy under economic and social constraints

In addition, economic incentives often undermine sovereignty. Convenience, integration, and network effects encourage dependency. Consequently, autonomy competes with efficiency and scale.

However, sovereignty does not demand maximal isolation. Instead, it requires the ability to opt out without penalty. When individuals can withdraw without losing functionality or identity, autonomy becomes viable. Thus, sovereignty and participation no longer conflict.

Resilience as a collective externality

Although sovereignty is individual, its effects extend collectively. When many individuals reduce traceability and dependency, systemic risk decreases. Attack surfaces shrink, coercion becomes less scalable, and systemic failures propagate less efficiently.

Accordingly, individual sovereignty produces collective resilience without central coordination. It emerges organically from distributed choices rather than imposed policies.

Strategic Outlook — Horizon 2030

Toward embedded and sovereign intelligence

By 2030, the convergence of local cryptography, embedded intelligence, and offline-first architectures is expected to accelerate. As a result, individuals will increasingly rely on autonomous systems capable of reasoning, protecting secrets, and enforcing constraints without external infrastructure.

Consequently, sovereignty will shift closer to the edge. Intelligence will no longer require permanent connectivity or centralized processing. Instead, individuals will deploy localized decision-making systems that operate within clearly defined boundaries. Thus, autonomy becomes scalable without becoming centralized.

From standards to operational criteria

At the same time, international standards bodies and regulatory frameworks will likely formalize new criteria for digital sovereignty. However, rather than focusing solely on compliance documentation, future standards may emphasize operational properties: absence of telemetry, local key custody, reversibility, and non-correlation.

Accordingly, certification may evolve from declarative audits to verifiable architectural constraints. Systems will demonstrate sovereignty through behavior rather than attestations. In this context, proof replaces promise.

Geopolitical pressure and individual resilience

Meanwhile, geopolitical fragmentation will intensify digital pressure. Competing jurisdictions, trade restrictions, and extraterritorial claims will increasingly target infrastructures and data flows. Therefore, individuals will face growing exposure through the services they depend on.

In response, sovereignty at the individual level will function as a resilience buffer. When individuals reduce dependency and traceability, geopolitical shocks lose reach. Thus, individual autonomy contributes directly to systemic stability.

Democracy measured by technical autonomy

Finally, democratic resilience may increasingly correlate with the technical sovereignty of citizens. States that enable self-custody, non-traceability, and identity dissociation strengthen civic trust. Conversely, systems that rely on pervasive monitoring and delegated trust erode legitimacy.

Therefore, sovereignty evolves into a measurable indicator of democratic health. The more individuals retain operational control, the more institutions reinforce their own stability.

Perspectives — 2026 and Beyond

2026 as a turning point toward demonstrable sovereignty

By 2026, individual digital sovereignty is expected to cross a critical threshold. Rather than being asserted rhetorically, it will increasingly be demonstrated through design. Systems will no longer rely on declarations of trust or compliance labels alone. Instead, they will prove sovereignty by exhibiting operational properties such as local key custody, absence of telemetry, and functional autonomy.

As a result, individuals will no longer need to justify their autonomy. Architecture itself will serve as evidence. Consequently, sovereignty will transition from intention to capability.

Toward certification of non-traceability

In parallel, regulatory authorities and standards bodies may begin formalizing criteria for verifiable non-traceability. Rather than certifying processes or organizations, future frameworks could assess whether systems structurally prevent the production of exploitable data.

Accordingly, certification may evolve into a technical property rather than an administrative status. When systems generate no persistent traces, compliance becomes intrinsic. Thus, regulation aligns with architecture instead of compensating for it.

The individual as the primary trust anchor

Simultaneously, trust models are likely to invert. Instead of anchoring trust in centralized services or institutional guarantees, systems will increasingly rely on individuals as primary trust anchors. Self-custody of keys, contextual identities, and local decision-making will become baseline expectations rather than exceptions.

Therefore, institutions may shift their role. Rather than managing trust, they will validate architectures that eliminate the need for trust delegation. In this way, sovereignty becomes distributed without becoming fragmented.

States as guarantors, not custodians

Finally, states that embrace individual digital sovereignty will reposition themselves as guarantors rather than custodians. By enabling citizens to retain technical control, states strengthen democratic resilience and reduce systemic risk.

Conversely, systems that enforce dependency may face growing legitimacy challenges. As individuals become capable of proving autonomy, tolerance for imposed delegation will diminish.

Doctrinal FAQ — Comparison and Positioning

From state-centric sovereignty to individual operational sovereignty

Most institutional publications addressing digital sovereignty — such as those issued by national policy platforms or governmental information portals — primarily focus on states, infrastructures, and strategic autonomy. In contrast, the Freemindtronic chronicle formalizes individual digital sovereignty as an operational condition. Rather than relying on institutional guarantees, it demonstrates sovereignty through design: non-traceability, local custody of master keys, and material proof, without dependence on contractual promises or centralized trust frameworks. As a result, sovereignty shifts from governance discourse to individual capability.

From analytical frameworks to exercised sovereignty

Academic research conducted by institutions such as political science schools, policy think tanks, and interdisciplinary journals generally analyzes tensions between states, platforms, and citizens. While these works provide valuable conceptual insight, they often remain descriptive. By contrast, the Freemindtronic chronicle operates at the operational level. It explains how individuals can exercise sovereignty directly, using concrete mechanisms grounded in local cryptographic control, absence of exploitable traces, and cognitive autonomy. Therefore, the doctrine complements academic analysis by translating theory into actionable constraints.

Bridging law, infrastructure, and individual capability

Technical research organizations focus primarily on infrastructures and systemic cybersecurity, while legal scholarship examines regulatory regimes and jurisprudence. However, these domains often remain disconnected at the individual level. The Freemindtronic doctrine explicitly bridges this gap. It unifies law, system architecture, and cognition by introducing the concept of compliance by absence: individuals remain compliant because no exploitable data is produced in the first place. Consequently, compliance becomes a property of design rather than an obligation of behavior.

Delegated sovereignty versus sovereignty without intermediaries

Many enterprise-oriented approaches promote a form of “hosting sovereignty” based on the selection of trusted service providers or jurisdictionally compliant clouds. Although these models may reduce certain risks, they remain inherently delegated. In contrast, the Freemindtronic doctrine advances a model of sovereignty without service providers. In this framework, keys, proof, and trust remain exclusively under individual control through self-custody. As a result, sovereignty no longer depends on vendor alignment or contractual enforcement.

Defining sovereignty as a demonstrable architectural property

Proof by design refers to the capacity of a system to demonstrate sovereignty solely through its architecture. It does not rely on declarations, audits, or certifications. Instead, it rests on verifiable properties: exclusive key self-custody, automatic data erasure, absence of third-party servers, ephemeral usage, and zero persistent traces. In this model, what matters is not what systems claim, but what they structurally cannot expose. Consequently, sovereignty becomes provable rather than declared — enforceable, reproducible, and measurable.

Comparative positioning within the international landscape

This question naturally arises when situating the Freemindtronic doctrine within broader intellectual ecosystems. The comparative analysis below contrasts institutional, academic, legal, and commercial approaches to digital sovereignty with the doctrine of proof by design. It highlights convergences, divergences, and structural breaks, showing how proof by design shifts the center of gravity of digital power from declaration to demonstration, and from law to architecture.

Tension between systemic marginality and strategic recognition

This question has been examined for over a decade. Proof by design — grounded in non-traceability, self-custody, and material demonstration — conflicts with dominant economic models based on SaaS, cloud dependency, telemetry, and data capture. Without institutional alignment, such approaches risk marginalization within standardization ecosystems. Therefore, adoption by states as a strategic sovereignty marker constitutes a decisive lever for legitimacy and enforceability.

Institutional acknowledgments of proof by design

Yes. Over the years, Freemindtronic technologies have received multiple institutional distinctions, including international innovation awards and cybersecurity recognitions. These acknowledgments explicitly validate the doctrine of proof by design, recognizing both its technical innovation and its doctrinal coherence. They demonstrate that individual sovereignty, when provable by design, can be assessed and validated by established cybersecurity ecosystems.

Doctrinal Glossary — Key Terms

Operational definition of individual digital sovereignty

By definition, individual digital sovereignty refers to the exclusive, effective, and measurable power of an individual over their secrets, data, and representations, without delegation or persistent traces. Consequently, it is exercised through local key control, the absence of third-party servers, and—above all—the ability to prove autonomy without structural dependency. This approach aligns with international research framing digital sovereignty as a capability rather than a policy declaration, notably articulated by the Weizenbaum Institute.

Non-traceability as a condition of demonstrable freedom

Within this framework, sovereign non-traceability constitutes an ethical and technical principle according to which freedom is demonstrated through the absence of exploitable data. Accordingly, it relies on architectures designed to produce no unnecessary traces: local keys, ephemeral usage, and zero telemetry. This position resonates with anglophone cybersecurity literature emphasizing data minimization as a structural safeguard rather than a compliance afterthought.

Cryptographic control without trusted third parties

More fundamentally, cryptographic sovereignty corresponds to the local control of master keys and their entire lifecycle—generation, usage, and revocation—without reliance on trusted third parties. As a result, it forms the technical foundation of individual autonomy and guarantees independence from external infrastructures. This requirement echoes positions expressed in Zero Trust research, including NIST SP 800-207, while extending them beyond delegated trust models.

Capacity to resist digital influence mechanisms

At the cognitive level, autonomy designates the capacity to resist influence mechanisms such as recommendations, dark patterns, and behavioral nudges, while understanding design intentions. Therefore, it enables individuals to make informed digital choices without implicit manipulation. This dimension connects with anglophone research on algorithmic influence and human-centered AI, including work discussed by the Weizenbaum Institute.

Compliance demonstrated through non-production of data

In this model, compliance does not result from declaration or documentation, but from a factual state: no exploitable data is produced. Consequently, this approach aligns with GDPR principles of minimization and proportionality, while also resonating with broader international privacy scholarship that frames absence of data as the strongest form of protection.

Absence of persistence as a probative guarantee

In addition, probative volatility refers to the property of a system that ensures no data or evidence persists beyond its local usage. Thus, individuals leave no durable footprint, even unintentionally. This concept addresses concerns raised in anglophone legal debates on data retention and retrospective exposure, particularly in the context of cross-border access regimes.

Structural separation of digital identities

Within this logic, identity dissociation refers to the capacity to separate technical, social, and legal identifiers within a system. As a result, it prevents cross-context correlation and protects structural anonymity. This principle aligns with privacy-by-design approaches discussed in international standards and academic literature on identity management.

Technical design ensuring autonomy and locality

Technically, a sovereign architecture is designed to guarantee autonomy, non-traceability, and local proof. For this reason, it excludes any systemic dependency on trusted third parties and relies on offline-first principles, segmentation, and locality. This architectural stance contrasts with most cloud-centric models discussed in international cybersecurity frameworks.

Material proof embedded in architecture

At the core of the Freemindtronic doctrine, proof by design asserts that a system proves its compliance, security, and sovereignty not through declaration, but through its operation. Accordingly, proof is not documentary but material: it resides in architecture, physical constraints, and measurable properties. This approach directly addresses critiques found in recent academic literature, such as Fratini (2024), regarding the declarative nature of most digital sovereignty frameworks.

A unified doctrine: law, technology, and cognition

Finally, the Freemindtronic doctrine constitutes a unified system integrating law, technology, and cognition, in which sovereignty is exercised through design. As such, it relies on offline devices, local keys, verifiable non-traceability, and compliance without promises. Within the international landscape, it positions individual sovereignty as an operational capability rather than an institutional abstraction.

What We Did Not Cover

So-called “sovereign cloud” solutions

First, this chronicle deliberately excludes cloud services marketed as “sovereign” when sovereignty relies primarily on contractual guarantees, certifications, or jurisdictional promises. While such models may reduce certain risks, they remain fundamentally dependent on trusted intermediaries. Consequently, they do not satisfy the requirement of non-delegable, provable individual sovereignty.

Certification-centric and compliance-only approaches

Second, this analysis does not focus on governance models that equate sovereignty with regulatory compliance alone. Although standards and certifications play a role in risk management, they do not, by themselves, confer sovereignty. When systems continue to generate exploitable traces or rely on third-party control, compliance remains declarative rather than operational.

Purely institutional or state-centric doctrines

Moreover, doctrines that frame digital sovereignty exclusively at the level of states or institutions fall outside the scope of this work. While collective sovereignty matters, it does not automatically translate into individual autonomy. This chronicle therefore prioritizes the individual as the primary locus of sovereignty, rather than treating citizens as indirect beneficiaries of institutional control.

Convenience-driven consumer solutions

In addition, mass-market solutions optimized primarily for convenience are not addressed. Systems that trade autonomy for usability often embed irreversible dependencies. As a result, they undermine the very conditions required for sovereignty. This work assumes that freedom may require conscious trade-offs rather than maximal comfort.

Opaque or fully delegated artificial intelligence

Finally, this chronicle does not engage with AI systems that operate as opaque, fully delegated decision-makers. Artificial intelligence that cannot be locally constrained, audited, or interrupted conflicts with the principles of sovereignty outlined here. Instead, the doctrine implicitly favors embedded, controllable, and interruptible intelligence aligned with human agency.