APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime represents one of the most strategically advanced and enduring cyber threat actors globally. In this comprehensive report, Jacques Gascuel examines their hybrid operations—combining state-sponsored espionage and cybercriminal campaigns—and outlines proactive defense strategies to mitigate their impact on national security and corporate infrastructures.

APT41 – Navigation Guide:

- History and Evolution

- APT41 – Key Statistics and Impact

- MITRE ATT&CK Matrix Mapping

- Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs)

- Structure and Operations

- Chrome V8 Exploits

- TOUGHPROGRESS Calendar C2 (May 2025)

- Mitigation and detection strategies

- Malware and tools

- Infrastructure

- Motivations and Targets

- Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

- Freemindtronic HSM Ecosystem – APT41 Defense Matrix

- Outlook and Next Steps

APT41 (Double Dragon / BARIUM / Wicked Panda) Cyberespionage & Cybercrime Group

Last Updated: April 2025

Version: 1.0

Source: Freemindtronic Andorra

Origins and Rise of the APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime Group

Active since at least 2012, APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime operations are globally recognized for their dual nature: combining state-sponsored espionage with personal enrichment schemes (Google Cloud / Mandiant). The group exploits critical vulnerabilities (Citrix CVE‑2019‑19781, Log4j / Log4Shell – CVE-2021-44228), UEFI bootkits (MoonBounce), and supply chain attacks (Wikipedia – Double Dragon).

APT41 – Key Statistics and Impact

- First Identified: 2012 (active since at least 2010 according to some telemetry).

- Number of Public CVEs Exploited: Over 25, including high-profile vulnerabilities like Citrix ADC (CVE-2019-19781), Log4Shell (CVE-2021-44228), and Chrome V8 (CVE-2025-6554).

- Confirmed APT41 Toolkits: Over 30 identified malware families and variants (e.g., DUSTPAN, ShadowPad, DEAD EYE).

- Known Victim Countries: Over 40 countries spanning 6 continents, including U.S., France, Germany, UK, Taiwan, India, and Japan.

- Targeted Sectors: Government, Telecom, Healthcare, Defense, Tech, Cryptocurrency, and Gaming Industries.

- U.S. DOJ Indictment: 5 named Chinese nationals in 2020 for intrusions spanning over 100 organizations globally.

- Hybrid Attack Model: Unique mix of espionage (state-backed) and cybercrime (personal enrichment) confirmed by Mandiant, FireEye, and the U.S. DOJ.

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix Mapping – APT41 (Enterprise & Defense Combined)

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1566.001 | Spearphishing with malicious attachments (ZIP+LNK) |

| Execution | T1059.007 | JavaScript execution via Chrome V8 |

| Persistence | T1542.001 | UEFI bootkit (MoonBounce) |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 | Obfuscated PowerShell scripts, memory-only loaders |

| Credential Access | T1555 | Access to stored credentials, clipboard monitoring |

| Discovery | T1087 | Active Directory enumeration |

| Lateral Movement | T1210 | Exploiting remote services via RDP, WinRM |

| Collection | T1119 | Automated collection via SQLULDR2 |

| Exfiltration | T1048.003 | Exfiltration via cloud services (Google Drive, OneDrive) |

| Command & Control | T1071.003 | Abuse of Google Calendar (TOUGHPROGRESS) |

Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs)

The APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime campaign has evolved into one of the most widespread and adaptable threats, impacting over 40 countries across critical industries.

- Initial Access: spear‑phishing, pièces jointes LNK/ZIP, exploitation de CVE, failles JavaScript (Chrome V8) via watering-hole, invitations malveillantes via Google Calendar (TOUGHPROGRESS).

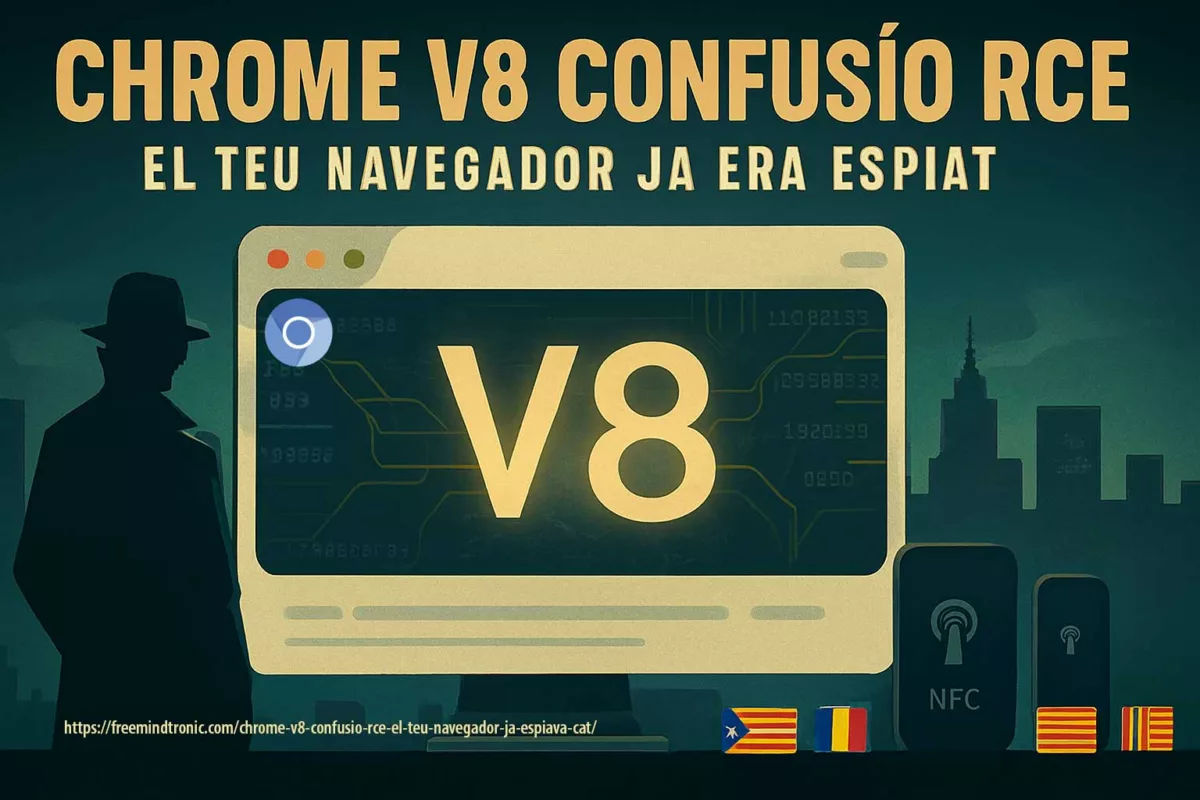

- Browser Exploitation: zero-day targeting Chrome V8 engine (e.g., CVE-2025-6554), enabling remote code execution via crafted JavaScript in spear-phishing and watering-hole campaigns.

- Persistence: bootkits UEFI (MoonBounce), loaders en mémoire (DUSTPAN, DEAD EYE).

- Lateral Movement: Cobalt Strike, credential theft, rootkits Winnti.

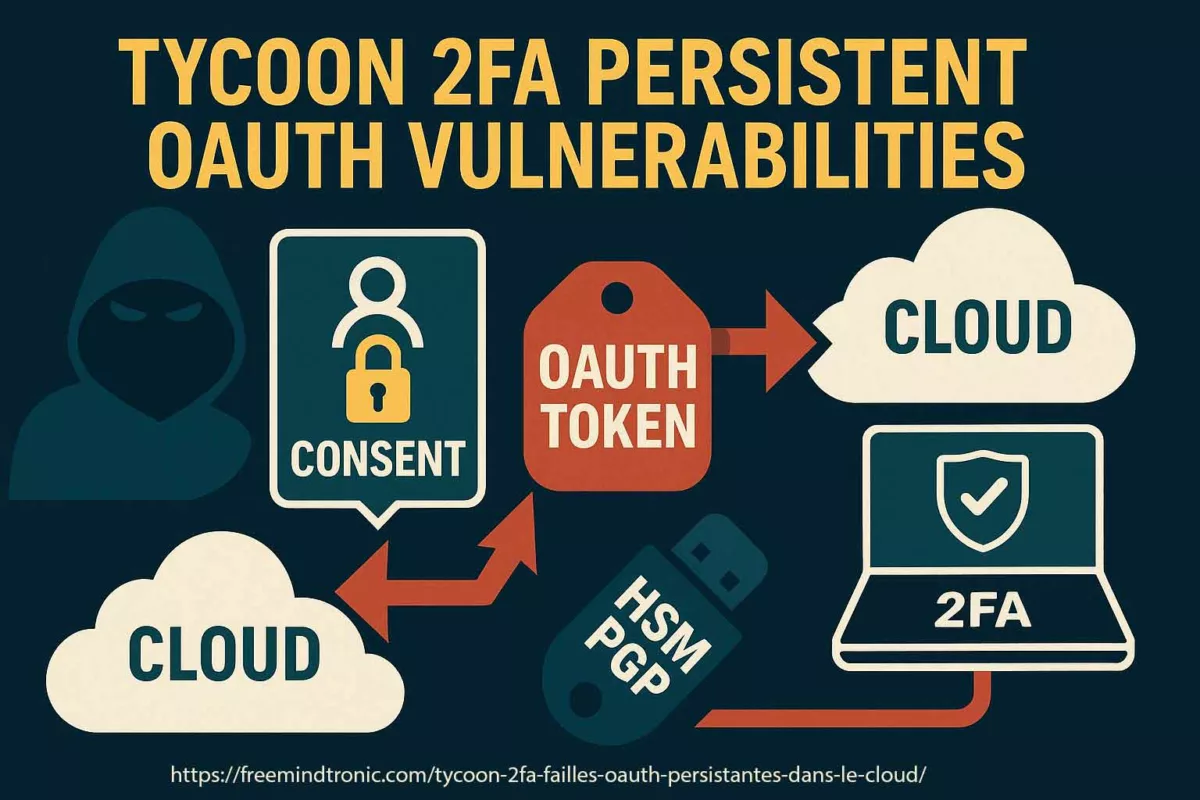

- C2: abus de Cloudflare Workers, Google Calendar/Drive/Sheets, TLS personnalisé

- TLS fingerprinting: Detect anomalies in self-signed TLS certs and suspicious CA chains (used in APT41’s custom TLS implementation).

- Exfiltration: SQLULDR2, PineGrove via OneDrive.

Global Footprint of APT41 Victimology

The global heatmap illustrates the spread of APT41 cyberattacks in 2025, with Chengdu, China marked as the origin. Curved arcs highlight targeted regions in North America, Europe, Asia, and beyond. heir targeting spans critical infrastructure, multinational enterprises, and governmental agencies.

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime – Structure and Operations

The APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime group is believed to operate as a contractor or affiliate of the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS), with ties to regional cyber units. Unlike other nation-state groups, APT41 uniquely combines state-sponsored espionage with financially motivated cybercrime — including ransomware deployment, cryptocurrency theft, and illicit access to video game environments for profit. This hybrid approach enables the group to remain operationally flexible while continuing to deliver on geopolitical priorities set by state actors.

Attribution reports from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) [DOJ 2020 Indictment] identify several named operatives associated with APT41, highlighting the structured and persistent nature of their operations. The group has demonstrated high coordination, advanced resource access, and the ability to pivot quickly between long-term intelligence operations and short-term financially motivated campaigns.

APT41 appears to operate with a dual-hat model: actors perform espionage tasks during official working hours and engage in financially driven attacks after hours. Reports suggest the use of a shared malware codebase among regional Chinese APTs, but with distinct infrastructure and tasking for APT41.

Attribution & Legal Action

In September 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice publicly indicted five Chinese nationals affiliated with APT41 for a global hacking campaign. Although not apprehended, these indictments marked a rare instance of legal attribution against Chinese state-linked actors. The group’s infrastructure, tactics, and timing patterns (active during GMT+8 working hours) strongly point to a connection with China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS).

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime – Chrome V8 Exploits

In early 2025, APT41 was observed exploiting a zero-day vulnerability in the Chrome V8 JavaScript engine, identified as CVE-2025-6554. This flaw allowed remote code execution through malicious JavaScript payloads delivered via watering-hole and spear-phishing campaigns.

This activity demonstrates APT41’s increasing focus on client-side browser exploitation to gain initial access and execute post-exploitation payloads in memory, often chained with credential theft and privilege escalation tools. Their ability to adapt to evolving browser engines like V8 further expands their operational scope in high-value targets.

Freemindtronic’s threat research confirmed active use of this zero-day in targeted attacks on European government agencies and tech enterprises, reinforcing the urgent need for browser-level monitoring and hardened sandboxing strategies.

TOUGHPROGRESS Calendar C2 (May 2025)

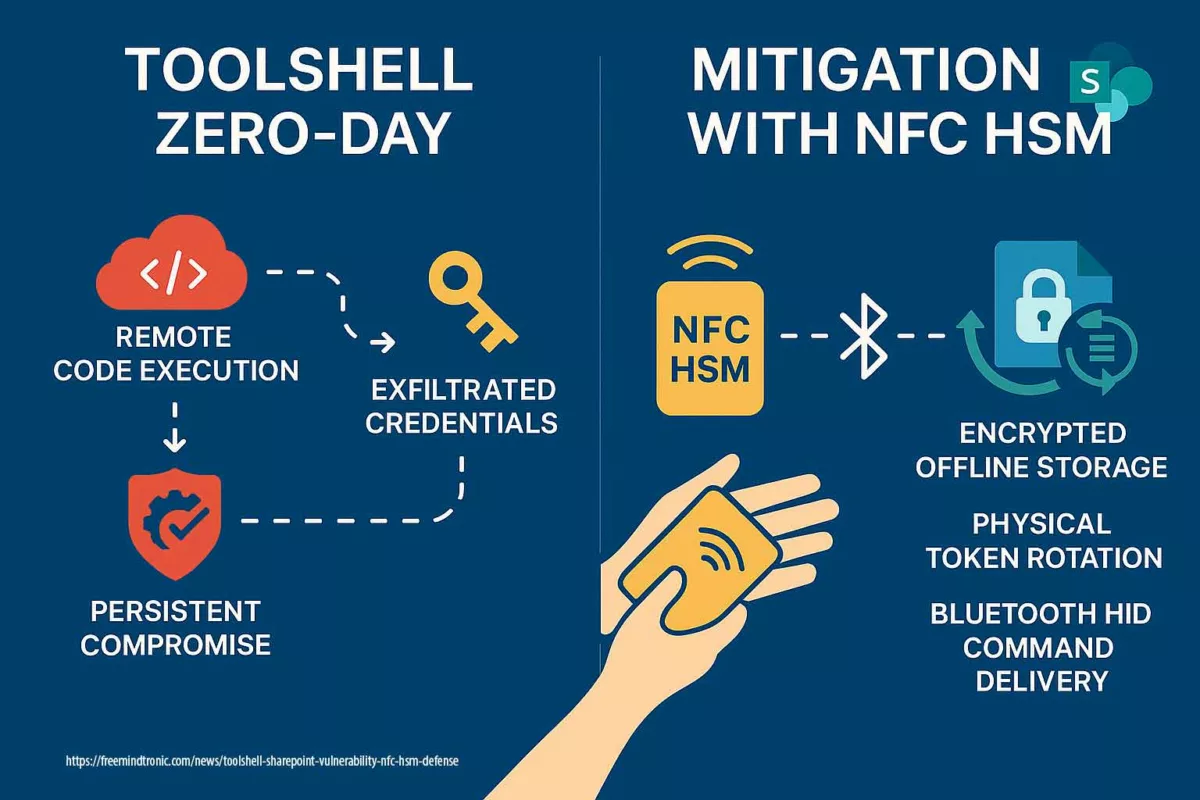

In May 2025, Google’s Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG), The Hacker News, and Google Cloud confirmed APT41’s abuse of Google Calendar for command and control (C2). The technique, dubbed TOUGHPROGRESS, involved scheduling encrypted events that served as channels for data exfiltration and command delivery. Google responded by neutralizing the associated Workspace accounts and Calendar instances.

Additionally, Resecurity published a June 2025 report confirming continued deployment of TOUGHPROGRESS on a compromised government platform. Their analysis revealed sophisticated spear-phishing methods using ZIP archives with embedded LNK files and decoy images.

To support detection, SOC Prime released Sigma rules targeting calendar abuse patterns, now incorporated by leading SIEM vendors.

Mitigation and Detection Strategies

- Update Management: proactive patching of CVEs (Citrix, Log4j, Chrome V8), rapid deployment of security fixes.

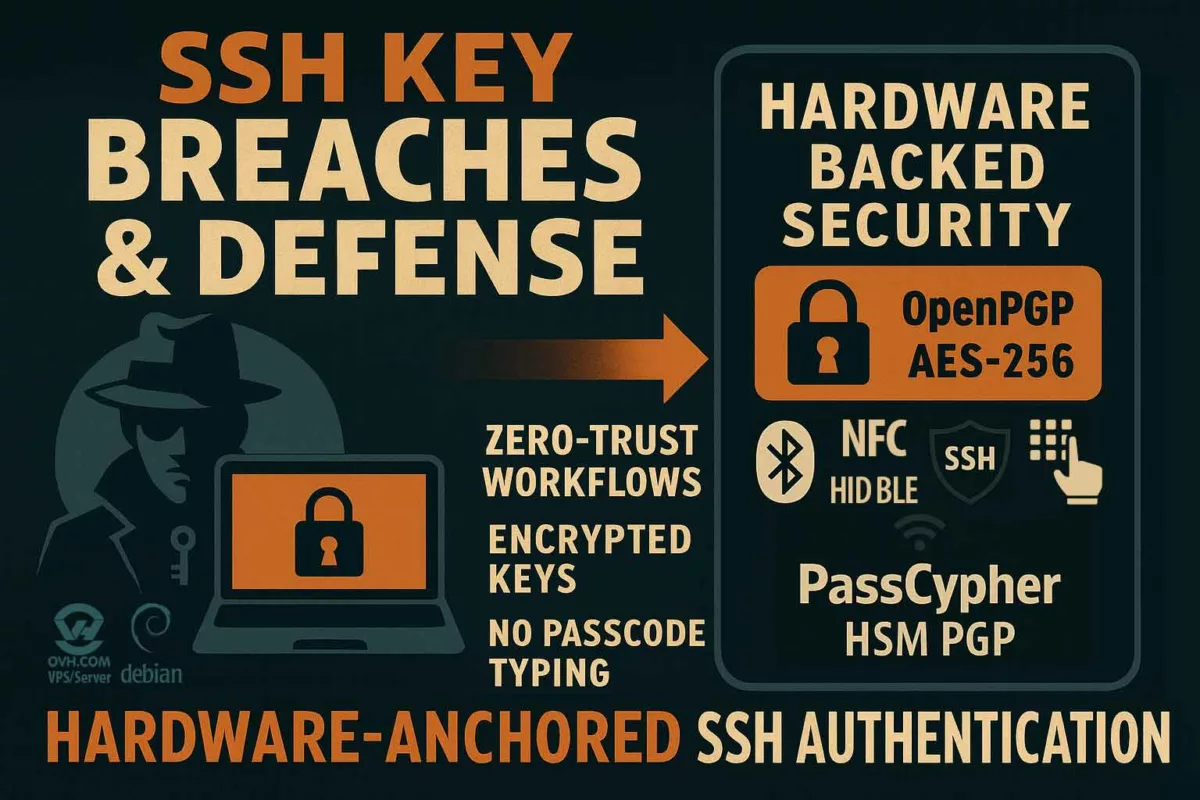

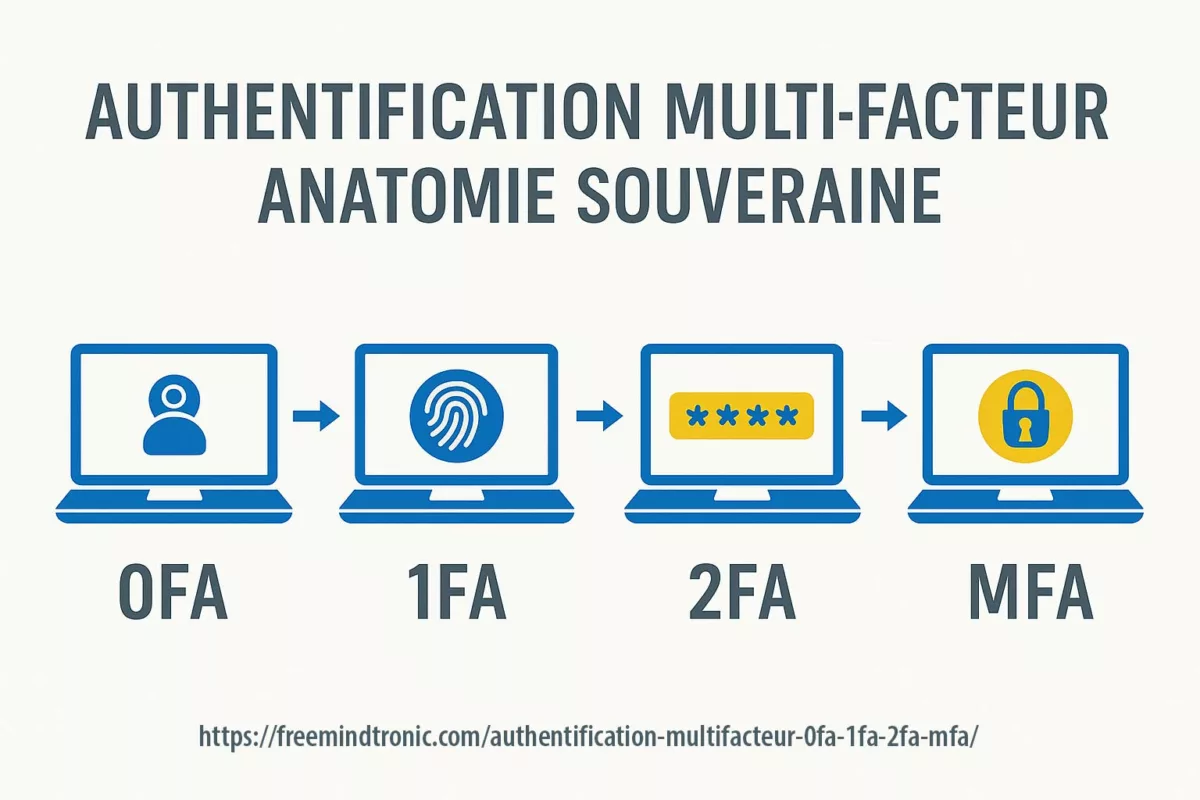

- UEFI/TPM Protection: enable Secure Boot, verify firmware integrity, use HSMs to isolate cryptographic keys from OS-level access.

- Cloud Surveillance: behavioral monitoring for abuse of Google Calendar, Drive, Sheets, and Cloudflare Workers via SIEM and EDR systems.

- Memory-based Detection: YARA and Sigma rules targeting DUSTPAN, DEAD EYE, and TOUGHPROGRESS malware families.

- Advanced Detection: apply Sigma rules from SOC Prime for identifying C2 anomalies via calendar-based techniques.

- Network Isolation: enforce segmentation and air gaps for sensitive environments; monitor DNS and TLS outbound patterns.

- Browser-level Defense: enable Chrome’s Site Isolation mode, enhance sandboxing, monitor abnormal JavaScript calls to the V8 engine.

- Key Isolation: use hardware HSMs like DataShielder to prevent unauthorized in-memory key access.

- Network TLS profiling: Alert on unknown certificate chains or forged CAs in outbound traffic.

Malware and Tools

- MoonBounce: UEFI bootkit linked to APT41, detailed by Kaspersky/Securelist.

- DUSTPAN / DUSTTRAP: Memory-resident droppers observed in a 2023 campaign.

- DEAD EYE, LOWKEY.PASSIVE: Lightweight in-memory backdoors.

- TOUGHPROGRESS: Abuses Google Calendar for C2, used in a late-2024 government targeting campaign.

- ShadowPad, PineGrove, SQLULDR2: Advanced data exfiltration tools.

- LOWKEY/LOWKEY.PASSIVE: Lightweight passive backdoor used for long-term surveillance.

- Crosswalk: Malware for targeting both Linux and Windows in hybrid cloud environments.

- Winnti Loader: Shared component used to deploy payloads across various Chinese APT groups.

- DodgeBox – Memory-only loader active since 2025 targeting EU energy sector, using PE32 x86 DLL signature evasion.

- Lateral Movement: Cobalt Strike, credential theft, Winnti rootkits, and legacy exploits like PrintNightmare (CVE-2021-34527).

Possible future threats include MoonWalk (UEFI-EV), a suspected evolution of MoonBounce, targeting firmware in critical systems (e.g., Gigabyte and MSI BIOS), as observed in early 2025. Analysts should anticipate deeper firmware-level persistence across high-value targets.

Use of Cloudflare Workers, Google APIs, and short-link redirectors (e.g., reurl.cc) for C2. TLS via stolen or self-signed certificates.

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime Motivations and Global Targets

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime campaigns are driven by a unique dual-purpose strategy, combining state-sponsored intelligence gathering with financially motivated cyberattacks. Unlike many APT groups that focus solely on espionage, APT41 leverages its advanced capabilities to infiltrate both government networks and private enterprises for political and economic gain. This hybrid model allows the group to target a wide range of industries and geographies with tailored attack vectors.

- Espionage: Governments (United States, Taiwan, Europe), healthcare, telecom, high-tech sectors.

- Cybercrime: Video game industry, cryptocurrency wallets, ransomware operations.

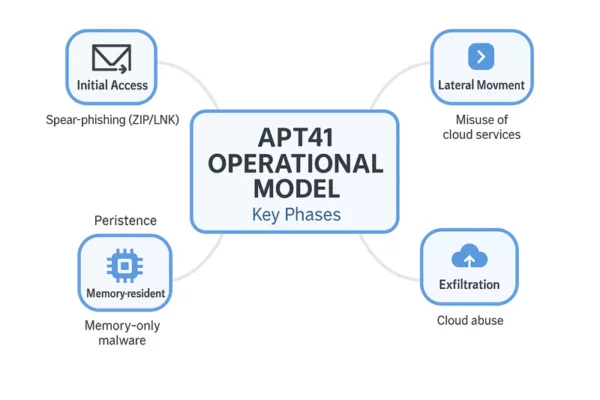

APT41 Operational Model – Key Phases

This mindmap offers a clear and concise visual synthesis of APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime activities. It highlights the key operational stages used by APT41, from initial access via spearphishing (ZIP/LNK) to data exfiltration through cloud-based Command and Control (C2) infrastructure.

Visual elements illustrate how APT41 combines memory-resident malware, lateral movement, and cloud abuse to achieve both espionage and monetization goals.

Mindmap: APT41 Operational Model – Tracing the full attack lifecycle from compromise to monetization.

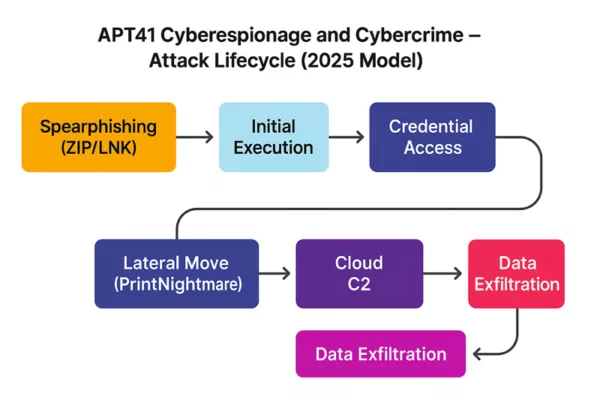

This section summarizes the typical phases of APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime operations, from initial compromise to exfiltration and monetization.

APT41 combines advanced cyberespionage with financially motivated cybercrime in a streamlined operational cycle. Their tactics evolve constantly, but the core lifecycle follows a recognizable pattern, blending stealth, persistence, and monetization.

- Initial Access: Spearphishing campaigns using ZIP+LNK attachments or fake software installers.

- Execution: Fileless malware or memory-only loaders such as DUSTPAN or DodgeBox.

- Persistence: UEFI implants like MoonBounce or potential MoonWalk variants.

- Lateral Movement: Exploitation of remote services (e.g., RDP, PrintNightmare), AD enumeration.

- Exfiltration: Use of SQLULDR2, OneDrive, Google Drive for data exfiltration.

- Command & Control: Cloud-based channels, including Google Calendar events and TLS tunnels.

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime – Attack Lifecycle (2025): From spearphishing to data exfiltration via cloud command-and-control.

Mobile Threat Vectors – Emerging Tactics

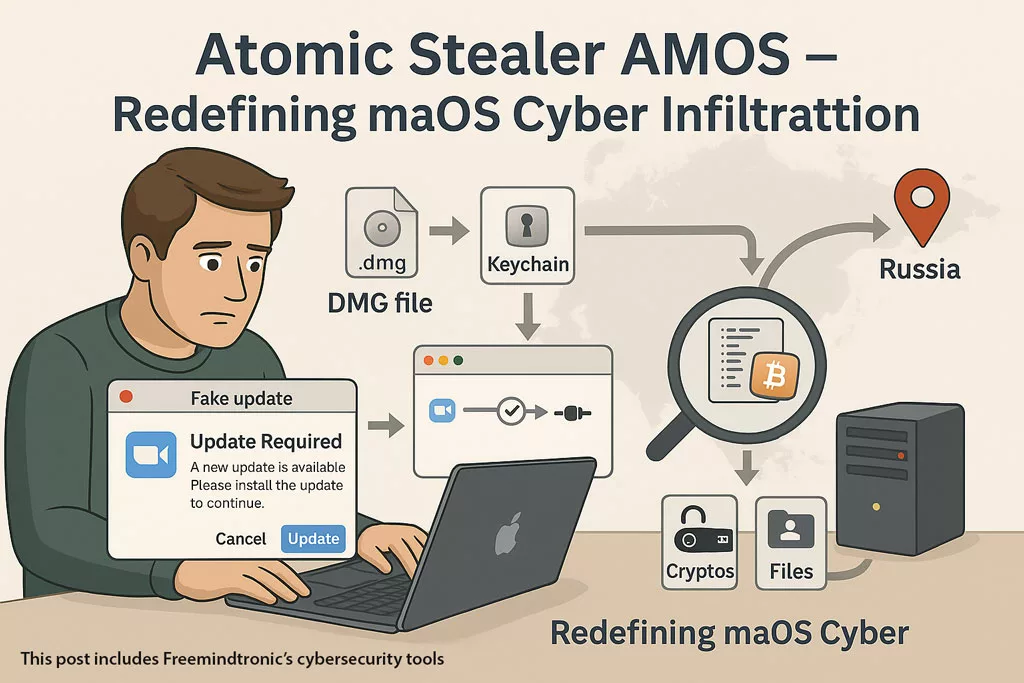

APT41 has tested malicious fake installers (.apk/.ipa) targeting mobile platforms, including devices used by diplomatic personnel. These apps are often distributed via private links or QR codes and may allow persistent remote access to mobile infrastructure.

Future Outlook on APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime Operations

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime exemplifies the hybrid model of modern digital threats, combining stealth operations with financial motives. Its use of stealth technologies—such as UEFI bootkits, memory-only malware, and cloud infrastructure abuse—demands a defense-in-depth approach supported by constantly refreshed threat intelligence. This document will be updated as new discoveries emerge (e.g., MoonWalk, DodgeBox…).

“APT41 represents a quantum leap in hybrid threat models—blurring the lines between state espionage and digital crime syndicates. Understanding their operational asymmetry is key to defending both critical infrastructure and intellectual sovereignty.”

— Jacques Gascuel, Inventor & CEO, Freemindtronic Andorra

APT41 Operational Lifecycle: From Cyberespionage to Cybercrime

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime operations typically begin with reconnaissance and spear-phishing campaigns, followed by the deployment of malware loaders such as DUSTPAN and memory-only payloads like DEAD EYE. Once initial access is achieved, the group pivots laterally across networks using credential theft and Cobalt Strike, often deploying Winnti rootkits to maintain long-term persistence.

Their hybrid lifecycle blends strategic espionage goals — like exfiltrating data from healthcare or governmental institutions — with opportunistic attacks on cryptocurrency platforms and gaming environments. This dual approach complicates attribution and enhances the group’s financial gain, making APT41 one of the most versatile and dangerous cyber threat actors to date.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

- Malware: MoonBounce, TOUGHPROGRESS, DUSTPAN, ShadowPad, SQLULDR2.

- Infrastructure: Google Calendar URLs, Cloudflare Workers, reurl.cc.

- Signatures: UEFI implants, memory-only malware, abnormal TLS behaviors.

Mitigation and Detection Measures

- Updates: Patch CVEs (Citrix, Log4j), update UEFI firmware.

- UEFI/TPM Protection: Enable Secure Boot, use offline HSMs for key storage.

- Cloud Surveillance: Track anomalies in Google/Cloudflare-based C2 traffic.

- Memory Detection: YARA/Sigma rules for TOUGHPROGRESS and DUSTPAN.

- EDR & Segmentation: Enforce strict network separation.

- Key Isolation: Offline HSM and PGP usage.

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime – Strategic Summary

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime operations continue to represent one of the most complex threats in today’s global cyber landscape. Their unique blend of state-aligned intelligence gathering and profit-driven criminal campaigns reflects a dual-purpose doctrine increasingly adopted by advanced persistent threats. From exploiting zero-days in Chrome V8 to abusing Google Workspace and Cloudflare Workers for stealthy C2 operations, APT41 exemplifies the modern hybrid APT. Organizations should adopt proactive defense measures, such as offline HSMs, UEFI security, and TLS fingerprint anomaly detection, to mitigate these risks effectively.

Freemindtronic HSM Ecosystem – APT41 Defense Matrix

The following matrix illustrates how Freemindtronic’s HSM solutions neutralize APT41’s most advanced techniques across both espionage and cybercriminal vectors.

Encrypted QR Code – Human-to-Human Response

To illustrate a real-world countermeasure against APT41 cyberespionage operations, this demo showcases the use of a secure encrypted QR Code that can be scanned with a DataShielder NFC HSM device. It allows analysts or security officers to exchange a confidential message offline, without relying on external servers or networks.

Use case: An APT41 incident response team can securely distribute an encrypted instruction or key via QR Code format — the message remains encrypted until scanned by an authorized device. This ensures end-to-end encryption, offline delivery, and complete data sovereignty.

Illustration of a secure QR code-based message exchange to counter APT41 cyberespionage and cybercrime threats.

🔐 Scan this QR code using your DataShielder NFC HSM device to decrypt a secure analyst message related to the APT41 threat.

| Threat / Malware | DataShielder NFC HSM | DataShielder HSM PGP | PassCypher NFC HSM | PassCypher HSM PGP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spear‑phishing / Macros | ✘ | ✔ Sandbox |

✘ | ✔ PGP Container |

| MoonBounce (UEFI) | ✔ NFC offline |

✔ OS‑bypass |

✘ | ✔ Secure Boot enforced |

| Cloud C2 | ✔ 100 % offline |

✔ Offline |

✔

Offline |

✔ No external connection |

| TOUGHPROGRESS (Google Abuse) | ✔

No Google API use |

✔ PGP validation |

✔ Encrypted QR only |

✔ Isolated |

| ShadowPad | ✔ No key in RAM |

✔ Offline use |

✔ No clipboard use |

✔ Sandboxed login |

Future Outlook on APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime Operations

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime exemplifies the hybrid model of modern digital threats, combining stealth operations with financial motives.Its use of stealth technologies—such as UEFI bootkits, memory-only malware, and cloud infrastructure abuse—demands a defense-in-depth approach supported by constantly refreshed threat intelligence. This document will be updated as new discoveries emerge (e.g., MoonWalk, DodgeBox…).

As of mid-2025, security researchers are closely monitoring the evolution of APT41’s toolset and objectives. Several indicators point toward the emergence of MoonWalk—a suspected successor to MoonBounce—designed to target UEFI environments in energy-sector firmware (Gigabyte/MSI BIOS suspected). Meanwhile, campaigns using DodgeBox and QR-distributed fake installers on Android and iOS platforms show a growing interest in covert mobile infiltration. These developments suggest a likely increase in firmware-layer intrusions, mobile surveillance tools, and social engineering payloads targeting diplomatic, industrial, and defense networks.

“APT41 represents a quantum leap in hybrid threat models—blurring the lines between state espionage and digital crime syndicates. Understanding their operational asymmetry is key to defending both critical infrastructure and intellectual sovereignty.”

— Jacques Gascuel, Inventor & CEO, Freemindtronic Andorra

Strategic Recommendations

- Deploy firmware validation routines and Secure Boot enforcement in critical systems

- Proactively monitor TLS traffic for custom fingerprinting or rogue CA chainsde constr

- Implement out-of-band communication tools like encrypted QR codes for human-to-human alerting

- Use memory-scanning EDRs and YARA rules tailored to new loaders like DodgeBox and DUSTPAN

- Monitor mobile ecosystems for signs of unauthorized app distribution or QR-based spearphishing

- Review permissions and logging for Google and Cloudflare API usage in corporate networks

APT41 Cyberespionage and Cybercrime exemplifies the hybrid model of modern digital threats…