Ledger Security Breaches have become a major indicator of vulnerabilities in the global crypto ecosystem. Beyond isolated technical flaws, it is the systemic correlations — hardware attacks, software exploits, third‑party data leaks, phishing scenarios — that shape today’s threat landscape, affecting individual users, exchanges, and trust infrastructures alike. Exploited by cybercriminals, state actors, and hybrid players, these breaches enable profiling, targeting, and manipulation of investors without necessarily compromising their private keys directly. Encryption protects private keys, but not relational, logistical, and behavioral metadata. This chronicle analyzes the major breaches from 2017 to 2026, their immediate and long‑term impacts, and the conditions for achieving true digital sovereignty against supply‑chain threats and third‑party dependencies.

Executive Summary — Ledger Security Breaches

⮞ Reading Note

This executive summary can be read in ≈ 3 to 4 minutes. It provides immediate insight into the central issue without requiring the full technical and historical analysis.

⚠️ Note on Supply Chain Resilience

The 2026 Global-e leak highlights what the CISA (Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency) defines as critical supply chain risks. According to their official guidelines, hardware security is only as strong as its weakest third-party link.

⚡ Key Findings

Since 2017, Ledger has faced several major breaches: seed phrase and firmware attacks, PCB modification, the 2020 database leak, the 2023 Connect Kit compromise, and the 2026 Global‑e data leak. These incidents show that threats arise not only from internal flaws but also from external dependencies and phishing vectors.

✦ Immediate Impact

- Massive customer data exposure (292K in 2020, Global‑e in 2026)

- Targeted phishing and harassment using personal information

- Transaction manipulation and private-key compromise in controlled 2018 attack scenarios

- Fragility of software supply chains and third‑party partners

⚠ Strategic Message

The real shift is not just technical compromise, but the repetition of breaches and their systemic exploitation. The threat becomes structural: automated phishing, doxxing, erosion of trust, and increased reliance on third parties. The risk is no longer occasional, but persistent.

The Shift from Trust to Proof

The repetition of Ledger Security Breaches proves that trust in a brand is not enough. Sovereignty requires proof. By implementing Segmented Key Authentication (WO2018154258), Freemindtronic moves control over critical secrets (seed phrases, private keys, credentials) from the vendor ecosystem directly into the user’s physical possession. This eliminates dependency on third-party infrastructure (e-commerce, update servers, logistics partners) for the custody and transfer of critical secrets.

⎔ Sovereign Countermeasure

There is no miracle solution against security breaches. Sovereignty means reducing exploitable surfaces: minimizing exposed data, using independent cold wallets (NFC HSM), strictly separating identity from usage, and maintaining constant vigilance against fraudulent communications.

Reading Parameters

Executive Summary: ≈ 3–4 min

Advanced Summary: ≈ 5–6 min

Full Chronicle: ≈ 30–40 min

First publication: December 16, 2023

Last update: January 7, 2026

Complexity level: High — security, crypto, supply‑chain

Technical density: ≈ 70 %

Languages available: EN · FR

Core focus: Ledger Security Breaches, crypto wallets, phishing, digital sovereignty

Editorial type: Chronicle — Freemindtronic Digital Security

Risk level: 9.2 / 10 — financial, civil, and hybrid threats

The chronicles displayed above ↑ belong to the Digital Security section. They extend the analysis of sovereign architectures, data black markets, and surveillance tools. This selection complements the present chronicle dedicated to the **Ledger Security Breaches (2017–2026)** and the systemic risks linked to hardware vulnerabilities, supply‑chain compromises, and third‑party providers.

- Executive Summary — Ledger Security Breaches

- Advanced Summary

- Chronicle — Ledger Security Breaches (2017–2026)

- 2018 — Seed Phrase Recovery Attack

- 2018 — Firmware Replacement Attack

- 2018 — PCB Modification Attack

- 2019 — Monero (XMR) Application Vulnerability

- Permanent Risk — Blind Signing

- 2020 — Ledger Customer Data Leak

- 2023 — Supply Chain: Connect Kit

- 2026 — Global-e Order-Data Leak

- ↳ Hybrid threats: phishing → physical coercion

- ↳ Global reactions: trust erosion & legal pressure

- ↳ SeedNFC: encrypted QR (air-gap sharing)

- ↳ Best practices

- Comparison: other crypto wallets

- Tech / Regulatory / Societal Projections

- Sovereign Alternatives — NFC HSM

- Strategic Outlook

Advanced Summary

A sequence of breaches that reveals a security-model problem

Since 2017, Ledger has faced a series of major incidents: seed phrase recovery attacks, firmware replacement, physical device modifications, application-level vulnerabilities (Monero), the massive 2020 customer database leak, the 2023 software supply-chain compromise, and the 2026 Global-e order-data leak. Taken separately, each event can be labeled an “incident.” Taken together, they reveal a security model problem.

The common denominator is not low-level cryptography, but the recurring necessity for critical secrets (seed phrases, private keys, identity-related metadata) to pass at some point through a non-sovereign environment: proprietary firmware, the host computer, connected applications, update servers, or an e-commerce partner.

From component security to ecosystem vulnerability

Ledger historically relied on the robustness of the hardware component itself. But from 2020 onward, the attack surface shifted to the peripheral ecosystem: customer databases, logistics services, software dependencies, user interfaces, notifications, and support channels.

The 2026 Global-e leak marks a turning point. Even without direct private-key compromise, exposure of delivery and order metadata turns users into persistent targets: ultra-targeted phishing, “delivery” social engineering, doxxing, and, in extreme cases, physical threats. Security is no longer only digital — it becomes civil and personal.

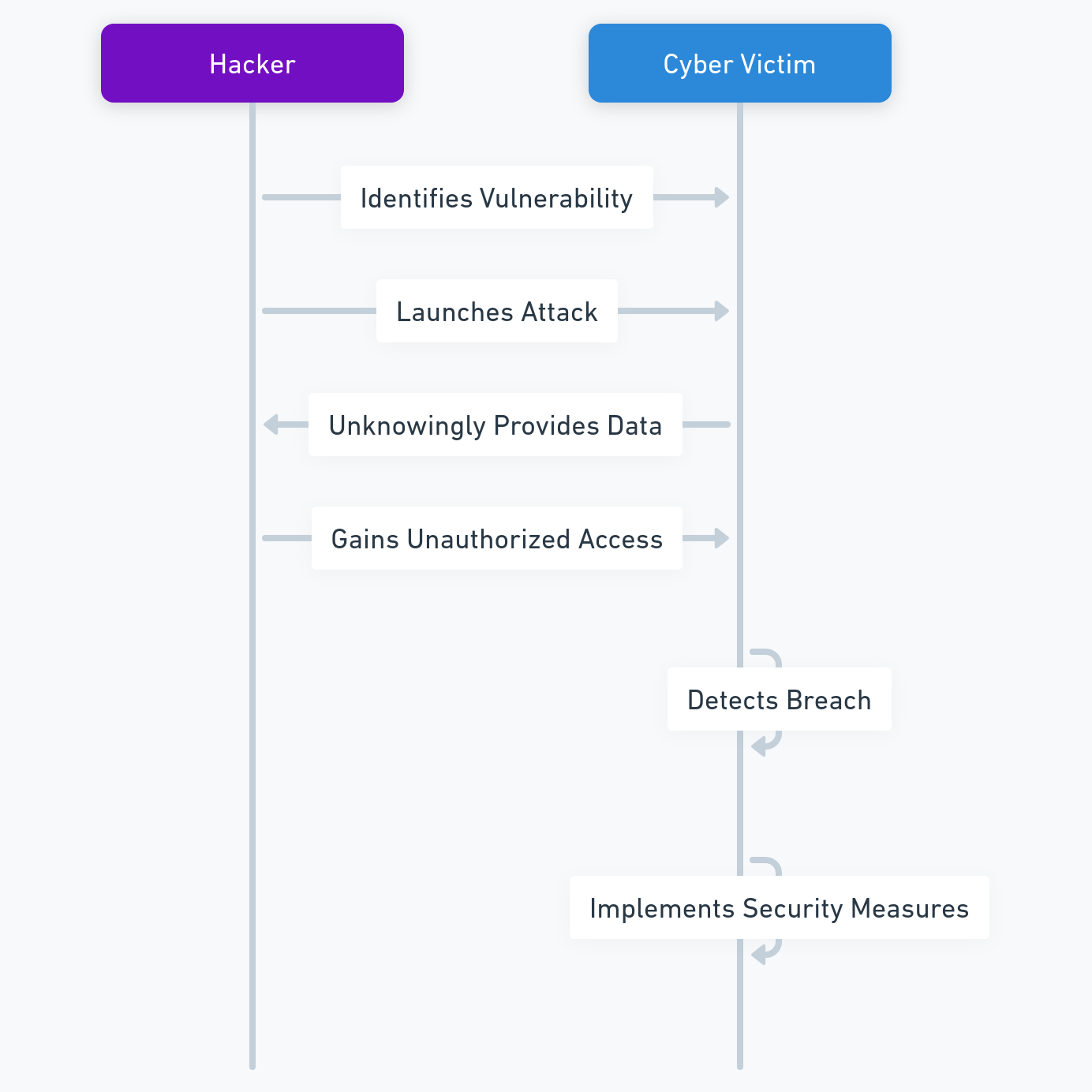

Why phishing and hybrid attacks become inevitable

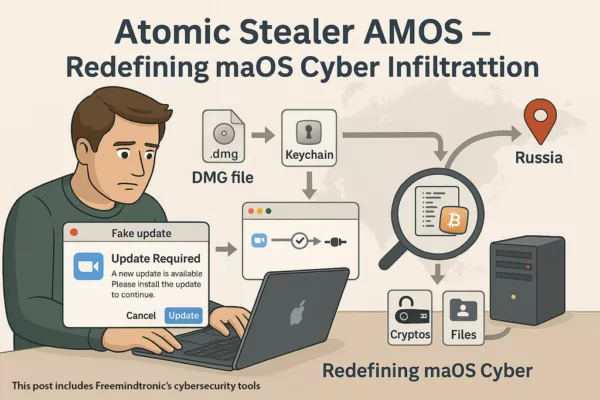

Once a user’s real identity is correlated with crypto ownership, phishing stops being opportunistic. It becomes industrial and personalized.

BITB attacks, fake updates, fake delivery incidents, or “compliance” scams exploit less a technical bug than the human factor, made vulnerable by exposed metadata.

In this context, hardening firmware or adding software warnings is not sufficient. The problem is not cryptographic signing — it is that the secret or its holder becomes identifiable, traceable, or remotely reachable.

Paradigm shift: from trust to hardware proof

Facing these structural limits, some approaches do not attempt to strengthen transaction signing — they aim to remove critical secrets from any connected ecosystem. Freemindtronic’s sovereign alternatives follow the opposite logic: instead of securing a connected stack, they seek to radically reduce dependencies. NFC HSM devices are battery-less, cable-less, and network-port-less, requiring no account, no server, and no cloud synchronization.

This paradigm shift is embodied by air-gap secret sharing: critical secrets (seed phrases, private keys, credentials for hot wallets or proprietary systems) can be transferred hardware → hardware from one SeedNFC HSM to another, via an RSA-4096 encrypted QR code using the recipient’s public key — without blockchain, without server, and without any transaction-signing function.

A structural answer to the failures observed since 2017

Where Ledger failures rely on supply chains, updates, and commercial relationships, sovereign architectures remove these breaking points by design. There is nothing to hack remotely, nothing to divert in a cloud, and nothing to extract from a third-party server. Even if visually exposed, an encrypted QR code remains unusable without physical possession of the recipient HSM.

This model does not promise “magic” security. It imposes deliberate responsibility: irreversibility of transfers, physical control, and operational discipline. But it eliminates the systemic attack vectors that have repeatedly surfaced since 2017.

Ledger Security Breaches (2017–2026): How to Protect Your Cryptocurrencies

Have you ever questioned the real level of security protecting your digital assets?

If you use a Ledger device, you may assume your funds are safe from hackers. Ledger is a French company widely recognized for its role in cryptocurrency security, offering hardware wallets designed to isolate private keys from online threats.

However, since 2017, Ledger Security Breaches have repeatedly challenged this assumption. Over time, multiple vulnerabilities have emerged—some exposing personal data, others enabling private-key compromise only in specific, controlled attack scenarios (e.g., physical access or manipulated environments). These weaknesses have allowed attackers not only to steal funds, but also to exploit users through phishing, identity correlation, and targeted coercion.

This chronicle provides a structured analysis of the major Ledger security incidents from 2017 to 2026. It explains how each breach was exploited, what risks they introduced, and why certain architectural choices amplify systemic exposure. Most importantly, it outlines practical and strategic approaches to reduce attack surfaces and regain control over cryptographic sovereignty.

Rather than focusing on fear or isolated failures, this analysis aims to help users understand the evolving threat landscape—and to distinguish between trust-based security and proof-based, sovereign architectures.

Ledger security incidents: How Hackers Exploited Them and How to Stay Safe

Ledger security breaches have exposed logistical and relational metadata (delivery address, purchase history, identity correlation), and in specific historical attack scenarios, enabled the compromise of private keys under controlled conditions. Ledger is a French company that provides secure devices to store and manage your funds. But since 2017, hackers have targeted Ledger’s e-commerce and marketing database, as well as its software and hardware products. In this article, you will discover the different breaches, how hackers exploited them, what their consequences were, and how you can protect yourself from these threats.

Ledger Security Breaches (2017–2026): From Hardware Attacks to Systemic Supply-Chain Risk

Have you ever wondered how safe your cryptocurrencies are? If you are using a Ledger device, you might think that you are protected from hackers and thieves. Ledger is a French company that specializes in cryptocurrency security. It offers devices that allow you to store and manage your funds securely. These devices are called hardware wallets, and they are designed to protect your private keys from hackers and thieves.

However, since 2017, Ledger has been the target of multiple incidents that exposed logistical and relational metadata (delivery address, purchase history, identity correlation) and, in specific historical attack scenarios, enabled private-key compromise under controlled conditions. These breaches could allow hackers to steal your cryptocurrencies or harm you in other ways. In this article, we will show you the different breaches that were discovered, how they were exploited, what their consequences were, and how you can protect yourself from these threats.

Ledger Security Issues: The Seed Phrase Recovery Attack (February 2018)

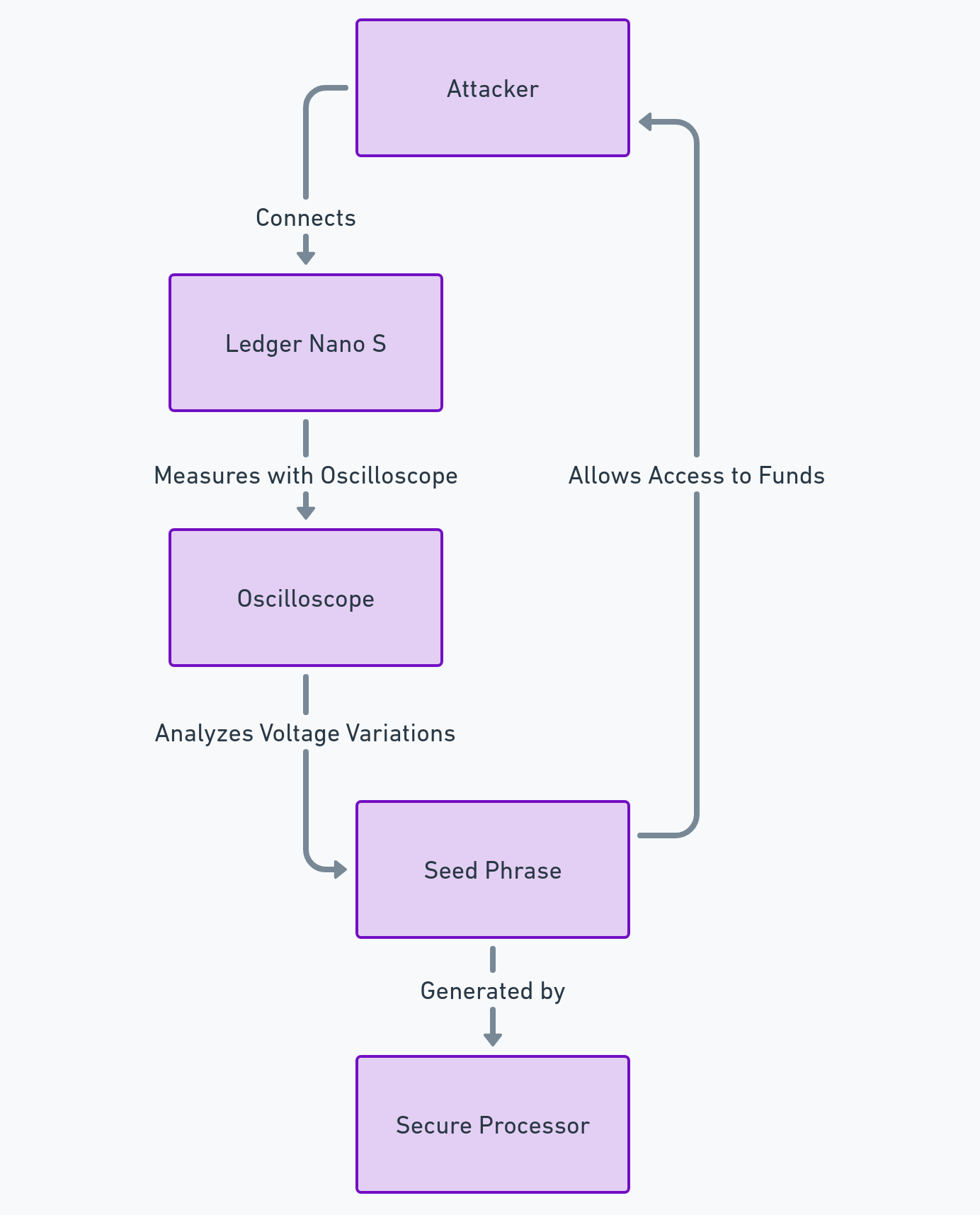

The seed phrase is a series of words that allows you to restore access to a cryptocurrency wallet. It must be kept secret and secure, as it gives full control over the funds. In February 2018, a security researcher named Saleem Rashid discovered a breach in the Ledger Nano S, which allowed an attacker with physical access to the device to recover the seed phrase using a side-channel attack.

How did hackers exploit the breach?

The attack consisted of using an oscilloscope to measure the voltage variations on the reset pin of the device. These variations reflected the operations performed by the secure processor of the Ledger Nano S, which generated the seed phrase. By analyzing these variations, the attacker could reconstruct the seed phrase and access the user’s funds.

Simplified diagram of the attack

- Number of potentially affected users: about 1 million

- Total amount of potentially stolen funds: unknown

- Date of discovery of the breach by Ledger: February 20, 2018

- Author of the discovery of the breach: Saleem Rashid, a security researcher

- Date of publication of the fix by Ledger: April 3, 2018

Scenarios of hacker attacks

- Scenario of physical access: The attacker needs to have physical access to the device, either by stealing it, buying it second-hand, or intercepting it during delivery. The attacker then needs to connect the device to an oscilloscope and measure the voltage variations on the reset pin. The attacker can then use a software tool to reconstruct the seed phrase from the measurements.

- Scenario of remote access: The attacker needs to trick the user into installing a malicious software on their computer, which can communicate with the device and trigger the reset pin. The attacker then needs to capture the voltage variations remotely, either by using a wireless device or by compromising the oscilloscope. The attacker can then use a software tool to reconstruct the seed phrase from the measurements.

Sources

1: Breaking the Ledger Security Model – Saleem Rashid published on March 20, 2018.

2: Ledger Nano S: A Secure Hardware Wallet for Cryptocurrencies? – Saleem Rashid published on November 20, 2018.

Ledger Security Flaws: The Firmware Replacement Attack (March 2018)

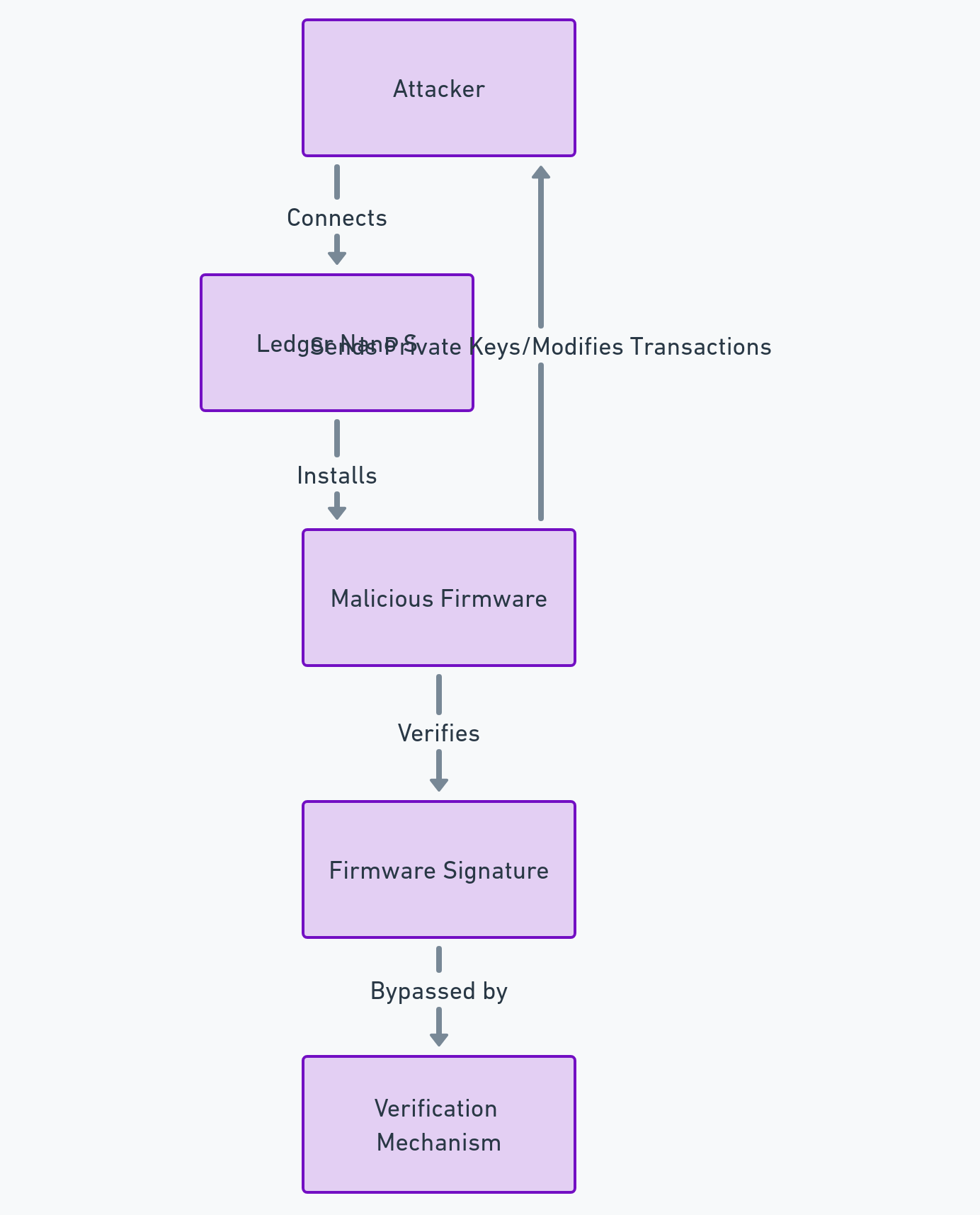

The firmware is the software that controls the operation of the device. It must be digitally signed by Ledger to ensure its integrity. In March 2018, the same researcher discovered another breach in the Ledger Nano S, which allowed an attacker to replace the firmware of the device with a malicious firmware, capable of stealing the private keys or falsifying the transactions.

How did hackers exploit the Ledger Security Breaches?

The attack consisted of exploiting a vulnerability in the mechanism of verification of the firmware signature. The attacker could create a malicious firmware that passed the signature check, and that installed on the device. This malicious firmware could then send the user’s private keys to the attacker, or modify the transactions displayed on the device screen.

Simplified diagram of the attack

Statistics on the breach

- Number of potentially affected users: about 1 million

- Total amount of potentially stolen funds: unknown

- Date of discovery of the breach by Ledger: March 20, 2018

- Author of the discovery of the breach: Saleem Rashid, a security researcher

- Date of publication of the fix by Ledger: April 3, 2018

Scenarios of hacker attacks

- Scenario of physical access: The attacker needs to have physical access to the device, either by stealing it, buying it second-hand, or intercepting it during delivery. The attacker then needs to connect the device to a computer and install the malicious firmware on it. The attacker can then use the device to access the user’s funds or falsify their transactions.

- Scenario of remote access: The attacker needs to trick the user into installing the malicious firmware on their device, either by sending a fake notification, a phishing email, or a malicious link. The attacker then needs to communicate with the device and send the user’s private keys or modify their transactions.

Sources

- Breaking the Ledger Security Model – Saleem Rashid published on March 20, 2018.

- Ledger Nano S Firmware 1.4.1: What’s New? – Ledger Blog published on March 6, 2018.

- Monero App Vulnerability Analysis – Ledger Donjon published on March 2019.

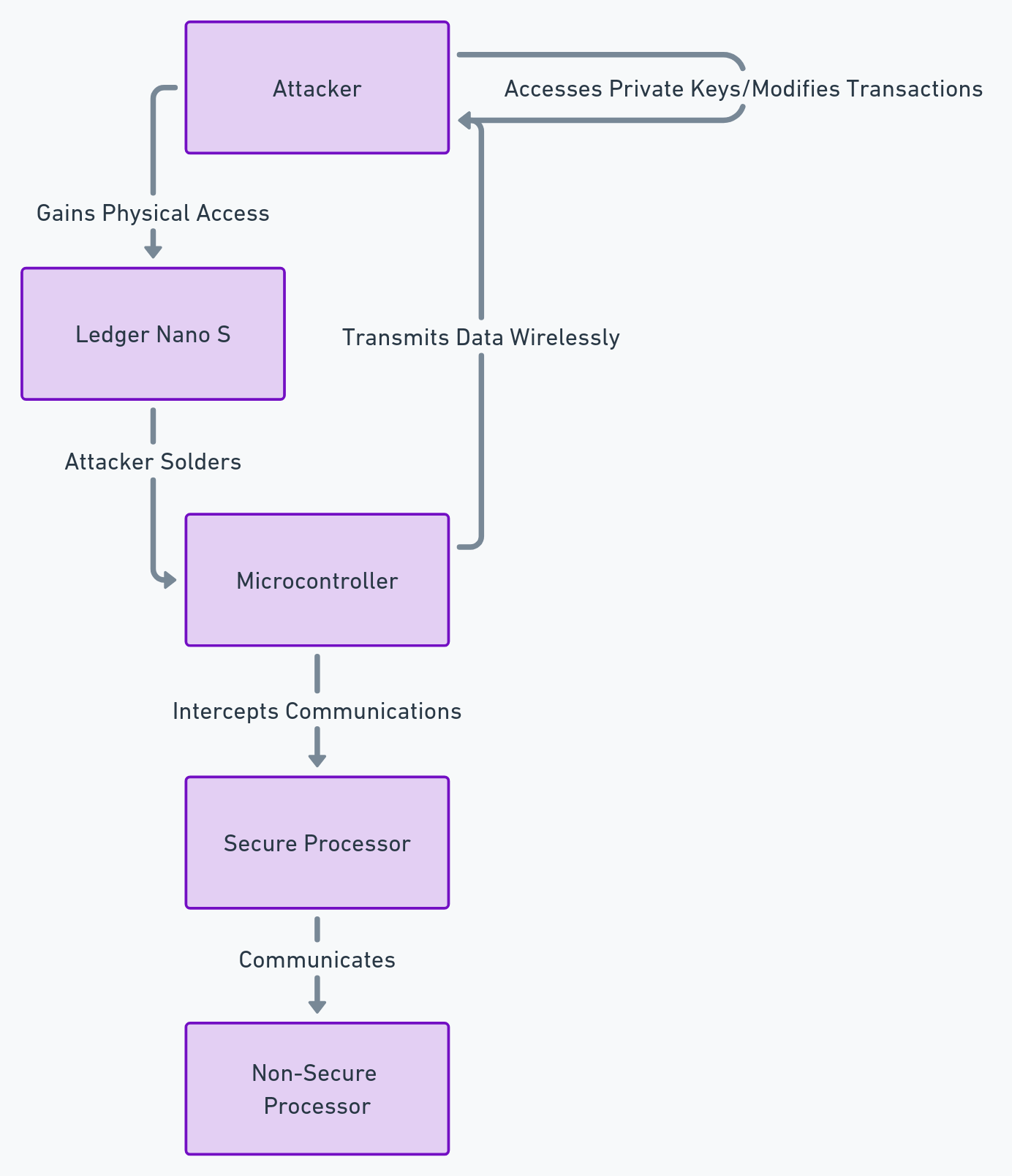

Ledger Security Incidents: The Printed Circuit Board Modification Attack (November 2018)

The printed circuit board is the hardware part of the device, which contains the electronic components. It must be protected against malicious modifications, which could compromise the security of the device. In November 2018, a security researcher named Dmitry Nedospasov discovered a breach in the Ledger Nano S, which allowed an attacker with physical access to the device to modify the printed circuit board and install a listening device, capable of capturing the private keys or modifying the transactions.

How did hackers exploit the breach?

The attack consisted of removing the case of the device, and soldering a microcontroller on the printed circuit board. This microcontroller could intercept the communications between the secure processor and the non-secure processor of the Ledger Nano S, and transmit them to the attacker via a wireless connection. The attacker could then access the user’s private keys, or modify the transactions displayed on the device screen.

Simplified diagram of the attack

Statistics on the breach

- Number of potentially affected users: unknown

- Total amount of potentially stolen funds: unknown

- Date of discovery of the breach by Ledger: November 7, 2019

- Author of the discovery of the breach: Dmitry Nedospasov, a security researcher

- Date of publication of the fix by Ledger: December 17, 2020

Scenarios of hacker attacks

- Scenario of physical access: The attacker needs to have physical access to the device, either by stealing it, buying it second-hand, or intercepting it during delivery. The attacker then needs to remove the case of the device and solder the microcontroller on the printed circuit board. The attacker can then use the wireless connection to access the user’s funds or modify their transactions.

- Scenario of remote access: The attacker needs to compromise the wireless connection between the device and the microcontroller, either by using a jammer, a repeater, or a hacker device. The attacker can then intercept the communications between the secure processor and the non-secure processor, and access the user’s funds or modify their transactions.

Sources

- [Breaking the Ledger Nano X – Dmitry Nedospasov] published on November 7, 2019.

- [How to Verify the Authenticity of Your Ledger Device – Ledger Blog] published on December 17, 2020.

Ledger Security Breaches: Monero Application Vulnerability (March 2019)

Not all cryptocurrencies interact with hardware wallets in the same way.

In March 2019, a critical vulnerability was discovered in the Monero (XMR) application for Ledger devices.

Unlike the 2018 physical attacks, this flaw was located in the communication protocol between the Ledger device and the Monero desktop client.

How Was the Vulnerability Exploited?

The flaw allowed a malicious or compromised Monero client to send manipulated transaction data to the Ledger device.

By exploiting a bug in the handling of change outputs, an attacker could:

- redirect funds to an address under their control without the user noticing on the Ledger screen, or

- under specific and controlled conditions, reconstruct the Monero private spend key by observing multiple device–host exchanges.

In this scenario, the hardware wallet signed cryptographically valid transactions based on manipulated inputs originating from the host software.

Incident Summary

- Potentially affected users: Monero (XMR) holders using Ledger Nano S or Nano X

- Reported loss: One documented case of approximately 1,600 XMR (~USD 83,000 at the time)

- Date of discovery: March 4, 2019

- Discoverers: Monero community & Ledger Donjon

- Patch released: March 6, 2019 (Monero app version 1.5.1)

Attack Scenarios

- Compromised software: The user interacts with an infected or unofficial Monero GUI wallet. During a legitimate transaction, the client silently alters transaction parameters to drain funds.

- Key reconstruction (controlled scenario): An attacker with malware on the host computer could theoretically reconstruct the Monero private spend key by intercepting and correlating multiple device–PC exchanges.

Important clarification: This incident did not involve a mass leak of private keys.

It demonstrated that, under specific conditions and with a compromised host environment, private key compromise was technically possible due to application-layer design flaws.

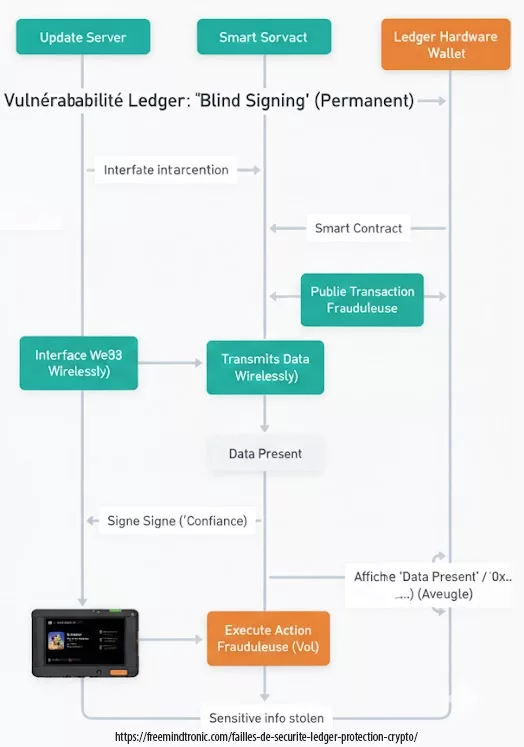

Structural “Blind Signing” Vulnerability: Signing in the Dark by Design (Permanent)

Blind Signing is not a temporary flaw nor a bug that can be patched with a firmware update.

It is a structural design limitation inherent to hardware wallets when confronted with the growing complexity of smart contracts.

As of 2026, it represents the #1 fund-theft vector in Web3, ahead of classic technical exploits.

Why Blind Signing Is Fundamentally Dangerous

A hardware wallet is supposed to enable conscious and verifiable validation of sensitive operations.

With Blind Signing, however, the device is unable to render the real intent of the contract being signed.

The user is typically presented with:

- a generic “Data Present” message

- unreadable hexadecimal strings

- or a partial, non-human-interpretable description

The signature becomes an act of faith.

The user no longer validates a understood action, but complies with an opaque interface.

Figure — Blind Signing: when the user signs a transaction whose real intent cannot be verified.

An Attack by Consent, Not by Circumvention

Unlike the 2018 Ledger incidents (seed recovery, firmware replacement, PCB modification),

Blind Signing does not attempt to break the hardware security.

It turns it against the user.

Everything is:

- cryptographically valid

- signed with the genuine private key

- irreversible on the blockchain

There is no detectable malware, no key extraction, no firmware compromise.

The loss is legally and technically attributable to the signature itself.

Impact and Scope

- Affected users: 100% of DeFi / NFT / Web3 users

- Estimated losses: hundreds of millions of USD (cumulative)

- Status: permanent and systemic risk

- Root cause: inability to verify signed intent

Typical Attack Scenarios

- Wallet drainers: a fake mint or airdrop leads to signing a contract that grants unlimited asset transfer rights.

- Hidden infinite approvals: the user unknowingly signs a permanent authorization. The wallet is emptied later, without any further interaction.

Conclusion:

Blind Signing marks a critical rupture: the private key remains protected, but effective security disappears.

The question is no longer “Is my wallet secure?”, but:

“Am I able to prove what I am signing?”

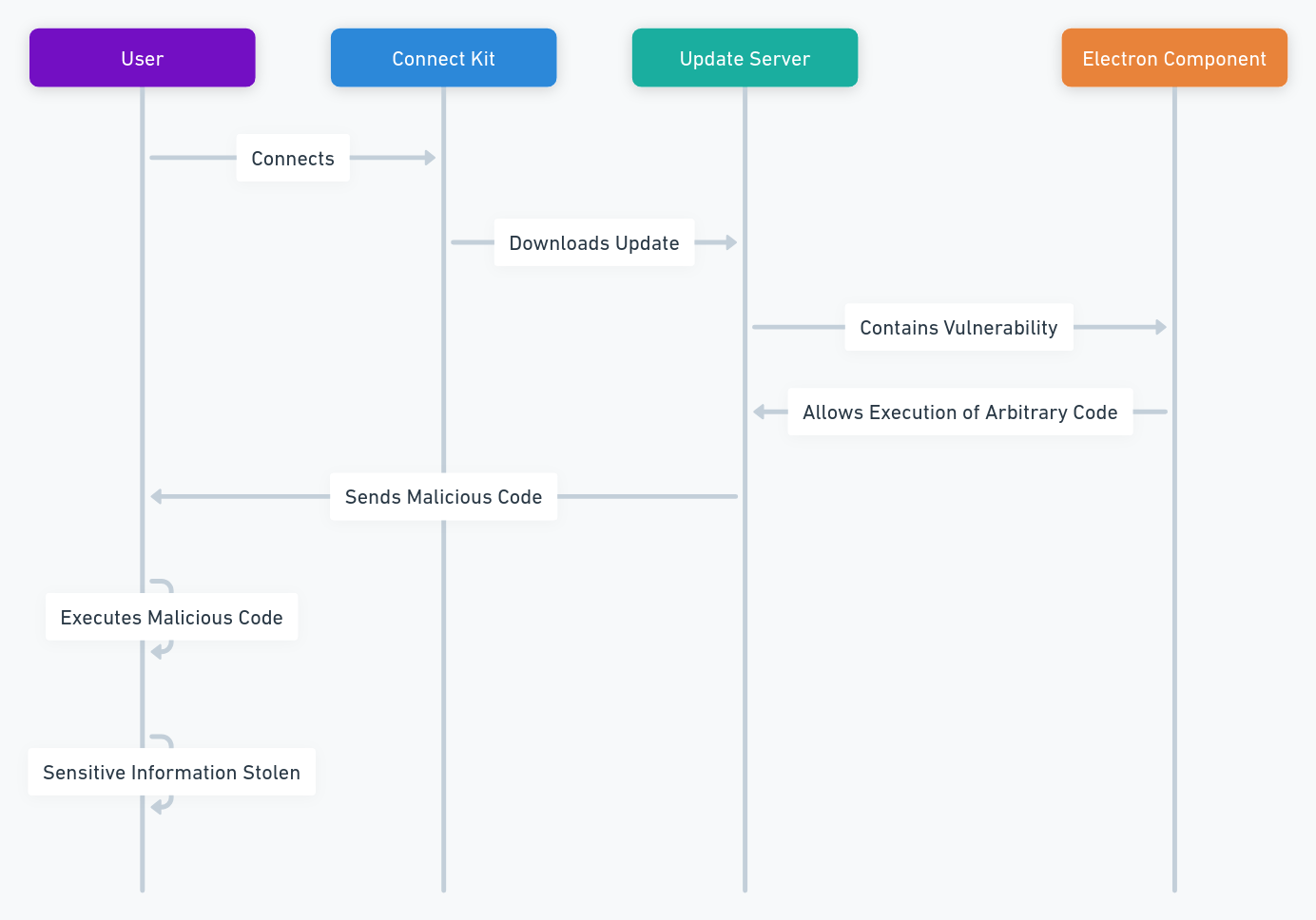

Ledger Security Breaches: The Connect Kit Attack (December 2023)

The Connect Kit is a software that allows users to manage their cryptocurrencies from their computer or smartphone, by connecting to their Ledger device. It allows to check the balance, send and receive cryptocurrencies, and access services such as staking or swap.

The Connect Kit breach was discovered by the security teams of Ledger in December 2023. It was due to a vulnerability in a third-party component used by the Connect Kit. This component, called Electron, is a framework that allows to create desktop applications with web technologies. The version used by the Connect Kit was not up to date, and had a breach that allowed hackers to execute arbitrary code on the update server of the Connect Kit.

Technical validation: This type of supply chain attack is classified under CWE-494 (Download of Code Without Integrity Check). You can monitor similar hardware wallet vulnerabilities on the MITRE CVE Database.

How did hackers exploit the Ledger Security Breaches?

The hackers took advantage of this breach to inject malicious code into the update server of the Connect Kit. This malicious code was intended to be downloaded and executed by the users who updated their Connect Kit software. The malicious code aimed to steal the sensitive information of the users, such as their private keys, passwords, email addresses, or phone numbers.

Simplified diagram of the attack

Statistics on the breach

- Number of potentially affected users: about 10,000

- Total amount of potentially stolen funds: unknown

- Date of discovery of the breach by Ledger: December 14, 2023

- Author of the discovery of the breach: Pierre Noizat, director of security at Ledger

- Date of publication of the fix by Ledger: December 15, 2023

Scenarios of hacker attacks

- Scenario of remote access: The hacker needs to trick the user into updating their Connect Kit software, either by sending a fake notification, a phishing email, or a malicious link. The hacker then needs to download and execute the malicious code on the user’s device, either by exploiting a vulnerability or by asking the user’s permission. The hacker can then access the user’s information or funds.

- Scenario of keyboard: The hacker needs to install a keylogger on the user’s device, either by using the malicious code or by another means. The keylogger can record the keystrokes of the user, and send them to the hacker. The hacker can then use the user’s passwords, PIN codes, or seed phrases to access their funds.

- Scenario of screen: The hacker needs to install a screen recorder on the user’s device, either by using the malicious code or by another means. The screen recorder can capture the screen of the user, and send it to the hacker. The hacker can then use the user’s QR codes, addresses, or transaction confirmations to steal or modify their funds.

Sources

- [https://thehackernews.com/2023/12/crypto-hardware-wallet-ledgers-supply.html] published on December 15, 2023.

Ledger Security Breaches: The Data Leak (December 2020)

The database is the system that stores the information of Ledger customers, such as their names, addresses, phone numbers and email addresses. It must be protected against unauthorized access, which could compromise the privacy of customers. In December 2020, Ledger revealed that a breach in its database had exposed the logistical and relational metadata (delivery address, purchase history, identity correlation) of 292,000 customers, including 9,500 in France.

How did hackers exploit the breach?

The breach had been exploited by a hacker in June 2020, who had managed to access the database via a poorly configured API key. The hacker had then published the stolen data on an online forum, making them accessible to everyone. Ledger customers were then victims of phishing attempts, harassment, or threats from other hackers, who sought to obtain their private keys or funds.

Simplified diagram of the attack :

Statistics on the breach

- Number of affected users: 292,000, including 9,500 in France

- Total amount of potentially stolen funds: unknown

- Date of discovery of the breach by Ledger: June 25, 2020

- Author of the discovery of the breach: Ledger, after being notified by a researcher

- Date of publication of the fix by Ledger: July 14, 2020

Scenarios of hacker attacks

- Scenario of phishing: The hacker sends an email or a text message to the user, pretending to be Ledger or another trusted entity. The hacker asks the user to click on a link, enter their credentials, or update their device. The hacker then steals the user’s information or funds.

- Scenario of harassment: The hacker calls or visits the user, using their logistical and relational metadata (delivery address, purchase history, identity correlation) to intimidate them. The hacker threatens the user to reveal their identity, harm them, or steal their funds, unless they pay a ransom or give their private keys.

- Scenario of threats: The hacker uses the user’s logistical and relational metadata (delivery address, purchase history, identity correlation) to find their social media accounts, family members, or friends. The hacker then sends messages or posts to the user or their contacts, threatening to harm them or expose their cryptocurrency activities, unless they comply with their demands.

Sources:

- [1] Ledger Blog : Ledger Data Breach: A Cybersecurity Update (January 2021)

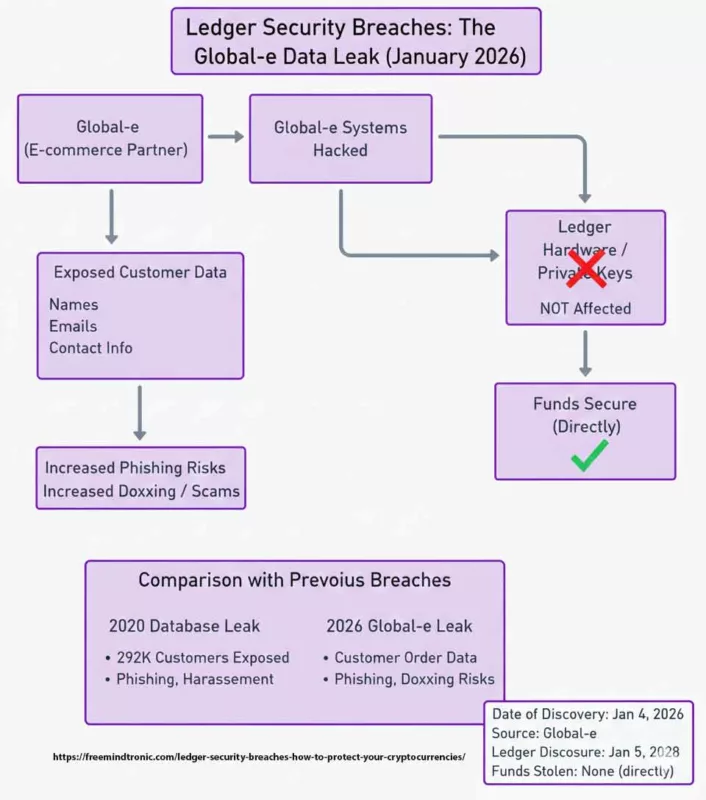

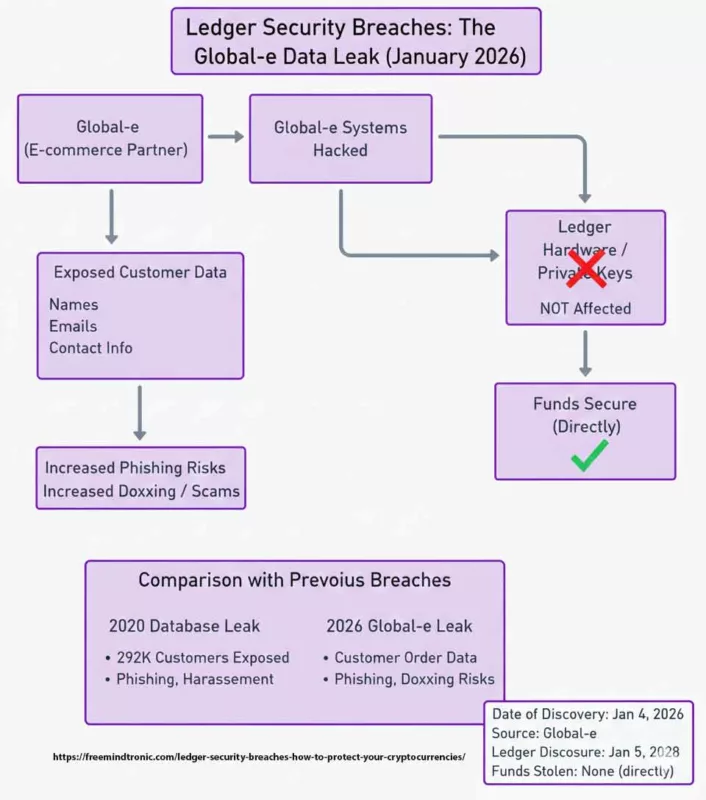

Ledger Security Breaches: The Global-e Data Leak (January 2026)

In January 2026, Ledger disclosed a new breach caused by its e-commerce partner Global-e.

Attackers compromised Global-e’s cloud systems, exposing customer names, email addresses, and delivery contact details used for online orders.

Unlike previous incidents, no seed phrases, private keys, or payment card data were compromised.

However, this leak significantly increased the risk of targeted phishing, doxxing, and long-term social engineering attacks against Ledger customers.

Figure — Global-e 2026 breach: how exposed order data enables phishing, doxxing, and coercive targeting.

Active Defense: Mitigating Global-e Leak Risks

The SeedNFC HSM ecosystem, combined with PassCypher HSM PGP, provides a structural response by shifting security into the user’s physical control:

- Reduced purchase metadata exposure: minimizing the collection and retention of identifiable data (name, address, phone) limits the long-term impact of e-commerce and logistics leaks such as 2020 and Global-e (2026).

- Hardware-based intent validation: critical actions require a physical NFC interaction, rendering remote phishing and fake-support attacks ineffective after a data leak.

- Anti-BITB & Anti-Iframe protection: blocks fake Ledger Live interfaces and credential-harvesting windows commonly used in post-leak phishing campaigns.

- Compromised credential detection: checks whether emails or passwords have appeared in previous breaches, preventing reuse and account takeover.

Global-e Breach Statistics

- Affected users: Not publicly disclosed (investigation ongoing as of January 2026).

- Exposed data: Customer names, emails, and delivery contact information.

- Impact on sensitive assets: None (private keys and funds remained secure).

- Date of discovery: January 4, 2026.

- Breach origin: Global-e cloud infrastructure.

⚠️ Critical Alert: Dark Web Resale & Persistent Targeting

A data breach is permanent. Once an identity is associated with a hardware wallet purchase,

the individual remains a high-value target for years.

Sovereign defense: By managing keys and credentials in a hardware-only environment such as SeedNFC HSM,

users can de-link their digital identity from centralized e-commerce databases and recurring leaks.

Official Sources & Expert References

- [1] Ledger Support: Global-e Incident Report (January 2026)

- [2] Europol (IOCTA): Stolen credential resale markets.

- [3] ANSSI / Cybermalveillance: Official guidance on data-leak risks

- [4] CoinDesk: Ledger warns of phishing risks after partner breach (January 2026).

Escalation of Threats: From Delivery Phishing to Physical Coercion

The Global-e delivery-data leak does not merely enable email scams.

It fuels hybrid attacks where digital exposure transitions into real-world coercion.

“Delivery” Phishing: Precision Social Engineering

Attackers exploit order history to send ultra-credible SMS or emails:

- Scenario: Fake courier messages (customs issue, address error, delayed shipment).

- Trap: A cloned Ledger interface requesting a recovery phrase to “unlock” delivery.

- Why it works: The victim is already expecting a shipment or update.

Physical Extortion & Home-Targeting

When physical addresses are exposed, the threat extends beyond cybercrime:

- Targeted home visits: Criminal groups identify where crypto holders live.

- Coercion: Victims are forced to sign irreversible transfers under threat.

- Family pressure: Attacks may involve relatives to break resistance.

“A leaked Ledger delivery address acts as a marker: it tells criminals where the vault is and who holds the key.” This reality forces a fundamental rethink of how security tools are purchased and how identity is exposed.

Official Statements and Expert Sources

- [1] Ledger Support: Official Incident Report – Global-e (January 2026)

- [2] Ledger Blog:Ledger Data Breach: A Cybersecurity Update (January 2021)

- [3] Europol (IOCTA): Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment – Resold credentials market

- [4] ANSSI (France): Official guidance on data leaks and extortion risks

- [5] CoinDesk: Ledger warns of phishing risks after partner hack (January 2026)

- [6] FBI (IC3):Internet Crime Complaint Center – Warnings on data breach-enabled scams

Global Reactions: Trust Erosion, Legal Pressure, and Community Backlash

The January 2026 Global-e order-data breach triggered a strong and immediate reaction across the global crypto ecosystem. Unlike earlier technical exploits, this incident reinforced a growing perception that the primary risk no longer lies in cryptography or hardware components, but in ecosystem-level dependencies: e-commerce partners, logistics providers, and identity-linked metadata.

Across English-speaking communities (Reddit, X, Discord, Telegram), the dominant sentiment was not surprise, but fatigue. For many users, Global-e represented the third major reminder—after 2020 and 2023—that hardware security alone does not guarantee user safety.

Recurring Themes in Anglophone Communities

- Collapse of “secure-by-brand” trust: Ledger’s hardware is still widely perceived as technically robust, but confidence in the surrounding commercial and data-handling ecosystem has eroded.

- Metadata as the real vulnerability: Users increasingly recognize that names, emails, delivery addresses, and purchase history enable profiling, targeting, and coercion—even when private keys remain secure.

- Phishing industrialization: Highly personalized scams (fake delivery notices, fake compliance alerts, fake support cases) are now viewed as an unavoidable consequence of large-scale data leaks.

From Cybersecurity to Legal and Regulatory Exposure

In the United States, United Kingdom, and European Union, discussions rapidly shifted toward legal accountability and consumer protection, backed by official frameworks:

- Class action risk (US / UK): Law firms are examining collective lawsuits for negligence and failure of duty of care, citing precedents in data breach litigation.

- Regulatory scrutiny: Data-protection authorities like the CNIL (EU) and the ICO (UK) have emphasized strict third-party dependency management under GDPR.

- Law-enforcement alerts: Agencies like Cybermalveillance.gouv.fr and the FBI (IC3) emphasize that crypto-related leaks increasingly enable hybrid crime, combining cyber-fraud with real-world intimidation.

Hybrid Threat Escalation: From Phishing to Physical Coercion

The Global-e breach illustrates a broader evolution of crypto-crime: the transition from purely digital theft to hybrid attack models, a trend confirmed by the INTERPOL Global Cybercrime reports.

Precision Phishing at Global Scale

Attackers leverage order metadata to craft highly credible messages. As reported by The Block, these campaigns include:

- Fake courier notifications (customs delay, address issues)

- Cloned Ledger Live portals requesting recovery phrases

- Social-engineering scripts tailored to purchase history

Physical Targeting and Extortion Risks

Once physical addresses are exposed, risks extend beyond cybercrime, aligning with the Chainalysis Crypto Crime evolution analysis:

- Home targeting: Criminal groups identify where high-value crypto holders live.

- Forced transactions: Victims are coerced into signing irreversible transfers via physical threats.

- Family leverage: Threats may extend to relatives to break resistance.

“A leaked delivery address does not steal funds—but it identifies the vault and the person holding the key.”

This realization has driven a growing demand for identity-minimizing, hardware-sovereign security models built on privacy-by-design principles —such as those prioritizing “Privacy by Design” by erasing all digital purchase records—to decouple asset protection from centralized logistics vulnerabilities.

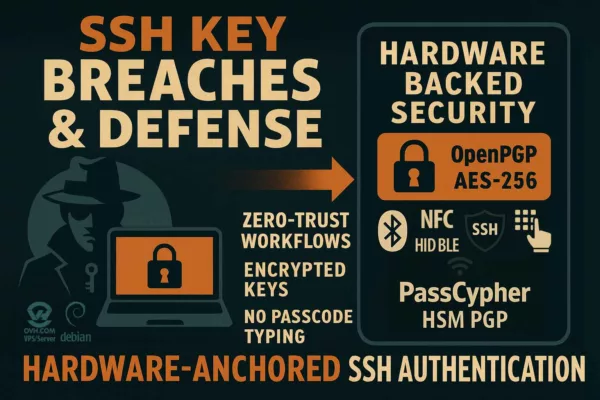

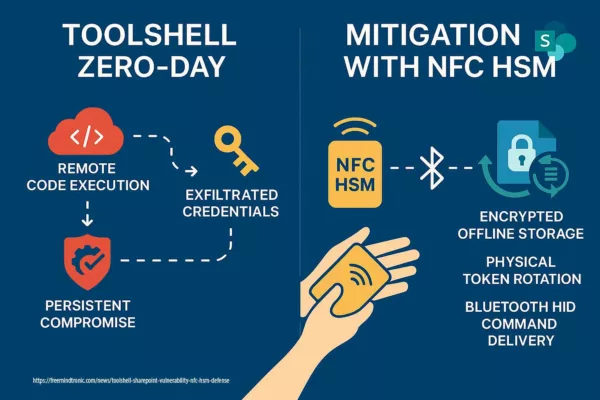

Permanent Air-Gapped Secret Sharing: RSA-4096 Encrypted QR Between SeedNFC HSM Devices

SeedNFC implements a fully air-gapped secret-sharing mechanism based on an

RSA-4096 encrypted QR code using the recipient’s public key.

The recipient must be another SeedNFC HSM, ensuring that only that device can decrypt and

import the secret directly into hardware.

The QR code is only an encrypted transport container. It can be displayed locally, sent as an image,

or even shown during a video call. Without physical possession of the recipient SeedNFC HSM,

the content remains mathematically unusable.

- Offline asymmetric encryption: the secret is never exposed in plaintext inside the QR code.

- Zero infrastructure: no server, no account, no database, no cloud.

- Operational + logical air-gap: sharing remains possible without any network connectivity.

This mechanism includes no revocation, no delay, and no expiration: the transfer is permanent by design.

It enables direct hardware → hardware transfer of critical secrets (seed phrases, private keys, access credentials)

between isolated HSM devices, with no software intermediary and no blockchain involvement.

Clarification: secret transfer ≠ transaction signing

SeedNFC HSM is not presented here as a transaction signer. Its role is upstream: to generate, store, and transfer secrets (seed phrases, private keys) or authentication data (IDs/passwords, hot-wallet access, proprietary systems) within a sovereign hardware boundary.

It can also store encrypted seed phrases from third-party wallets (Ledger, Trezor, software hot wallets, etc.) and their associated private keys, without depending on the original vendor’s firmware, software, or infrastructure.

Depending on the use case, data can be injected in a controlled way into an application field through Bluetooth HID keyboard emulation (e.g., migration, restore, login).

Web complement: for browser workflows, equivalent controlled input can be triggered via the Freemindtronic browser extension (explicit field selection). This eliminates exposure via clipboard, temporary files, or cloud sync, and strongly reduces risk from classic software keyloggers, since the user does not type anything.

Scope note: like any input, data may still become observable at the display point or on a compromised host (screen capture, application malware). The goal is to remove “copy/paste + file” vectors and human typing—not to make an infected system “invulnerable”.

Important: transferring a private key transfers ownership (full control over the associated funds).This is relevant for backup, migration, inheritance, or off-chain ownership transfer, but must be used with strict operational discipline.

Comparison with other crypto wallets

Ledger is not the only solution to secure your cryptocurrencies. There are other options, such as other hardware wallets, software wallets, or exchanges. Each option has its advantages and disadvantages, depending on your needs and preferences.

Other Hardware Wallets

For example, other hardware wallets, such as Trezor, offer similar features and security levels as Ledger, but they may have different designs, interfaces, or prices.

Software Wallets

Software wallets, such as Exodus or Electrum, are more convenient and accessible, but they are less secure and more vulnerable to malware or hacking.

Exchanges

Exchanges, such as Coinbase or Binance, are more user-friendly and offer more services, such as trading or staking, but they are more centralized and risky, as they can be hacked, shut down, or regulated.

| Security Vector | Traditional USB Wallet | Freemindtronic NFC HSM |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Attack Surface | High (USB ports, Battery, Screen) | Minimal (No ports, No battery) |

| Data Persistence | Risk of flash memory wear | High (EviCore long-term integrity) |

| Side-Channel Leakage | Possible (Power consumption analysis) | Immune (Passive induction) |

Cold Wallet Alternatives

Another option is to use a cold wallet, such as SeedNFC HSM, which is a patented HSM that uses NFC technology to create, store, and transfer cryptographic secrets (seed phrases, private keys, credentials) in an offline, hardware-only environment, without any connection to the internet or a computer. It also allows you to create up to 100 cryptocurrency wallets and check the balances from this NFC HSM.

Internationally Patented Sovereign Technology

To address the structural flaws identified in traditional hardware wallets, Freemindtronic uses a unique architecture protected by international patents (WIPO). These technologies ensure that the user remains the sole master of their security environment.

- Access Control System Patent WO2017129887

Guarantees physical-to-digital integrity by ensuring the HSM can only be triggered by a specific, intentional human action, preventing remote exploitation. - Segmented Key Authentication System Patent WO2018154258

Provides a defense-in-depth mechanism where secrets are fragmented. This prevents a “single point of failure,” making “Connect Kit” type attacks or firmware replacements ineffective.

Technological, Regulatory, and Societal Projections

The future of cryptocurrency security is uncertain and challenging. Many factors can affect Ledger and its users, such as technological, regulatory, or societal changes.

Technological changes

It changes could bring new threats, such as quantum computing, which could break the encryption of Ledger devices, or new solutions, such as biometric authentication or segmented key authentication patented by Freemindtronic, which could improve the security of Ledger devices.

Regulatory changes

New rules or restrictions could affect Cold Wallet and Hardware Wallet manufacturers and users, such as Ledger. For example, KYC (Know Your Customer) or AML (Anti-Money Laundering) requirements could compromise the privacy and anonymity of Ledger users. They could also ban or limit the use of cryptocurrencies, which could reduce the demand and value of Ledger devices. On the other hand, other manufacturers who have anticipated these new legal constraints could have an advantage over Ledger. Here are some examples of regulatory changes that could affect Ledger and other crypto wallets:

- MiCA, the proposed EU regulation on crypto-asset markets, aims to create a harmonized framework for crypto-assets and crypto-asset service providers in the EU. It also seeks to address the risks and challenges posed by crypto-assets, such as consumer protection, market integrity, financial stability and money laundering.The Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation, specifically Title V on service provider obligations, is now the gold standard. Freemindtronic technologies are designed to align with the Official Regulation (EU) 2023/1114, ensuring privacy while meeting compliance needs.

- U.S. interagency report on stablecoins recommends that Congress consider new legislation to ensure that stablecoins and stablecoin arrangements are subject to a federal prudential framework. It also proposes additional features, such as limiting issuers to insured depository institutions, subjecting entities conducting stablecoin activities (e.g., digital wallets) to federal oversight, and limiting affiliations between issuers and commercial entities.

- Revised guidance from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) clarifies the application of FATF standards to virtual assets and VASPs. It also introduces new obligations and recommendations for PSAVs, such as the implementation of the travel rule, licensing and registration of PSAVs, and supervision and enforcement of PSAVs.

These regulatory changes could have significant implications for Ledger and other crypto wallets. They could require them to comply with new rules and standards, to obtain new licenses or registrations, to implement new systems and processes, and to face new supervisory and enforcement actions.

Societal changes

Societal changes could influence the perception and adoption of Ledger and cryptocurrencies, such as increased awareness and education, which could increase the trust and popularity of Ledger devices, or increased competition and innovation, which could challenge the position and performance of Ledger devices. For example, the EviSeed NFC HSM technology allows the creation of up to 100 cryptocurrency wallets on 5 different blockchains chosen freely by the user.

Technological Alternatives for Absolute Sovereignty

The persistence of Ledger Security Breaches demonstrates that relying on a single centralized manufacturer creates a systemic risk. Today, decentralized alternatives developed by Freemindtronic in Andorra offer a paradigm shift: security based on hardware proof and physical intent, rather than brand trust.

Technologies such as EviCore NFC HSM and EviSeed NFC HSM are not just wallets; they are contactless cybersecurity ecosystems. Unlike Ledger, these devices are battery-less and cable-less, eliminating physical ports (USB/Bluetooth) as attack vectors.

Internationally Patented Security

Freemindtronic’s architecture is anchored by two fundamental international patents (WIPO) that solve the structural flaws found in traditional hardware wallets:

- Segmented Key Authentication System (WO2018154258): Prevents the compromise of the whole seed or private key, even if the environment is attacked.

- Access Control System (WO2017129887): Ensures that the HSM can only be triggered by the user’s physical intent via NFC, neutralizing remote software threats.

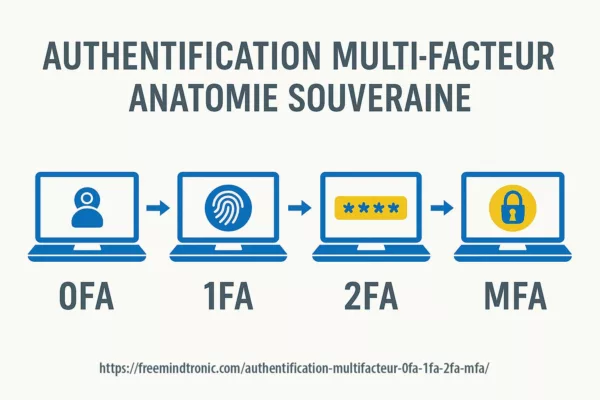

Unified Security: Hardware-Based Password Management

One of the most innovative features of the SeedNFC HSM is its integration of the EviPass NFC HSM technology. This addresses the “human factor” exploited in phishing scams.

- Decentralized & Passwordless: Manage non-morphic passwords without ever storing them on a computer.

- Physical Entropy: Immunity to keyloggers and screen recorders used in the Connect Kit attacks.

- Contactless Convenience: Secure auto-fill by simply tapping your device.

Universal Access: Smartphone & Desktop Integration

Advanced “Air-Gap” Input: Keyboard Emulation

To bypass compromised clipboards, Fullsecure with Inputstick enables hardware-level data injection.

How it works: Your smartphone acts as a Bluetooth HID Keyboard, “typing” secrets directly into any device.

- No Clipboard Exposure: Secrets never pass through the computer’s buffer.

- Hardware Injection: Neutralizes software-based keyloggers relying on human keystroke capture.

Important clarification: transferring a private key is not a transaction. It is an off-chain transfer of ownership, granting full control over the associated assets.

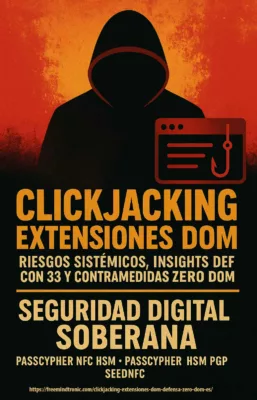

Active Defense: Neutralizing BITB & Redirection Attacks

The SeedNFC HSM ecosystem, when paired with the free PassCypher HSM PGP version and the browser extension, provides a unique multi-layered shield against modern web threats:

-

- Anti-BITB (Browser-In-The-Browser): The extension features a dedicated anti-iframe system. It detects and blocks malicious windows that simulate fake login screens—a common tactic used to steal Ledger credentials.

- Automated Corruption Check: Integrated with Have I Been Pwned, the system automatically checks if your IDs or passwords have been compromised in historical leaks, ensuring you never use “vulnerable” credentials.

- End-to-End Encrypted Auto-fill: Sensitive data is encrypted directly within the SeedNFC HSM on your Android device. It is only decrypted at the final millisecond of injection into the browser, ensuring that no plain-text data ever resides in the computer’s memory.

How to use: Open the Freemindtronic Android App (where SeedNFC is embedded), tap your HSM to your phone, and let the secure bridge handle the encrypted injection directly into your Chrome or Edge browser.

Best Practices to Protect Yourself

- Never share your seed phrase or private keys — no support, update, delivery, or compliance process ever requires them.

- Assume all inbound communication is hostile by default — (email, SMS, phone, social media). Always verify via official, manually accessed channels.

- Strictly separate identity from asset ownership — use a dedicated email, avoid real-name linkage, and minimize purchase metadata exposure.

- Avoid blind signing whenever possible — never sign transactions or approvals you cannot fully interpret and verify.

- Prefer sovereign, hardware-only cold storage — (e.g., patented NFC HSM architectures) that do not rely on vendor servers, firmware updates, or e-commerce ecosystems.

- Keep secrets out of connected environments — avoid clipboards, cloud sync, screenshots, password files, and shared devices.

- Use hardware-enforced authentication and password management — to neutralize phishing, BITB, and credential reuse.

- Plan for irreversible scenarios — define secure procedures for backup, migration, inheritance, and off-chain ownership transfer.

- Accept operational responsibility — sovereignty implies discipline, physical control, and acceptance that some actions cannot be undone.

Securing the Future: From Vulnerability to Digital Sovereignty

Since 2017, the trajectory of Ledger Security Breaches has served as a critical case study for the entire crypto ecosystem. While Ledger remains a pioneer in hardware security, the recurring incidents—ranging from early physical exploits to the massive 2026 Global‑e data leak—demonstrate that a “secure device” is no longer enough. The threat has shifted from the chip itself to the systemic supply chain and the exposure of relational data.

The January 2026 incident confirms a persistent reality: even when private keys remain shielded, the leak of customer metadata (names, emails, and order history) creates a permanent risk of targeted phishing, doxxing, and social engineering. This highlights the inherent danger of centralized e‑commerce databases and the fragility of relying on third‑party partners for a product whose core promise is absolute security.

The Sovereign Alternative: Security by Design

To break this cycle of dependency, the paradigm must shift toward decentralized hardware security. This is where patented technologies developed by Freemindtronic in Andorra provide a structural response:

- Physical Intent & Access Control (WO2017129887): Eliminates the remote attack surface by requiring a physical, contactless validation that cannot be spoofed by malicious software updates.

- Segmented Key Authentication (WO2018154258): Protects against systemic breaches (like the Connect Kit attack) by ensuring that secrets are never centralized or fully exposed, even in a compromised environment.

This model does not promise convenience. It requires strict operational discipline, physical control, and acceptance of irreversibility.

For Ledger users, vigilance remains the primary line of defense. Respecting strict digital hygiene—verifying every communication via the official Ledger help center and using dedicated, non‑identifiable contact info for purchases—is essential. However, for those seeking to eliminate the “third‑party risk” entirely, transitioning to battery‑less, contactless, and patented NFC HSM solutions represents the next step in achieving true digital sovereignty.

As the crypto landscape evolves through 2026 and beyond, the lesson is clear: Don’t just trust the brand—trust the architecture.

Technical Reference: The EviCore and SeedNFC architectures are based on WO2017129887 and WO2018154258 patents. Developed by Freemindtronic Andorra for absolute digital sovereignty.